From A Hard Day’s Night to This Is Spinal Tap: The Big Tent of Rock and Roll on Film

Fred Goodman on the Evolution of the Rock and Roll Movie

By the beginning of the 1970s, the rock and roll movie had become a big tent covering a myriad of styles and intentions, some of the films very serious indeed. In Europe, auteurs Jean-Luc Godard and Michelangelo Antonioni both measured the rock scene and exploited it for their own artistic ends with Sympathy for the Devil/One Plus One and Blow-Up, respectively, while Britain’s Nicolas Roeg put a trippy and cryptic rock and roll spin on gangster movies with Performance starring Mick Jagger—a trick he would reproduce for science fiction films in 1976 with David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth.

In the US, Arthur Penn, riding high on the phenomenal success of Bonnie and Clyde, selected Alice’s Restaurant (1969) as his next film. Unlike his European arthouse cohorts, Penn aimed to make an impact in the mainstream, but his artistic intentions were no less earnest: the director had a healthy respect for both the music and the antiwar movement, and Alice’s Restaurant sympathetically gave heft to the counterculture by locating its roots in America’s liberal progressive movement.

None of this happened in a vacuum. As Don’t Look Back demonstrated, films about rock got more ambitious because rock music was increasingly ambitious. “Good Golly, Miss Molly” and “Like a Rolling Stone” are both great rock singles, but beyond that, it is hard to say what else they have in common, and any films you key off them are going to be radically different. Politics, nostalgia, art, race, sexuality, gender, drugs—whatever rock took into its DNA started to be expressed in its films. Around the same moment that rock and roll spurs George Lucas to make the wistfully sentimental American Graffiti, it also leads British actor Richard O’Brien to write the wickedly transgressive Rocky Horror Show and its film adaptation.

The stylistic distance between those two pictures tells a truth: by the early ’70s, rock had splintered into a myriad of subgenres, styles, and tastes. And though Hollywood has always been ready to turn singers like Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and Doris Day into movie stars, filmmakers had also grown acutely aware of the drawing power of rockers.

Many musicians are willing to take that plunge, but it’s not always easy to judge whether their mere presence imparts anything of rock’s spirit and swagger unless it’s a charismatic superstar like Elvis, Jagger, Prince, or David Bowie whose stardom will always overshadow and color the character they portray. But casting a rock star doesn’t necessarily make the film a rock and roll movie.

At the peak of his recording career, James Taylor made Two-Lane Blacktop, an outstanding road picture that costarred Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys and had no musical overtones save their casting, which simply suggested the producers hoped to attract a youthful audience.

Likewise, 1991’s Rush, in which Gregg Allman played a terrifying drug dealer, or the blaxploitation action films like Truck Turner and Three Tough Guys that soul star Isaac Hayes made in the ’70s, which had little in common with Hayes’s albums beyond the smooth, easygoing hipness he projected in both spheres. Sometimes a film with a rocker is just a movie, and sometimes a rocker—like John Doe of the band X, who has appeared in dozens of films—is pursuing a separate, parallel career.

Beyond the disco era, rock films provide a window for viewing the trends and tribes that have defined the music scene at any moment.

It’s certainly a lot harder to connect Will Smith’s or Mark Wahlberg’s recording career to either man’s roles as actors than it is with Courtney Love, Iggy Pop, Tom Waits, Marianne Faithfull (all primarily supporting and character actors), or even a few extremely successful movie stars like Ice Cube, Madonna, or Queen Latifah. That may be because the roles they favor as actors have more in common with the personalities projected in their music.

The splintering of rock and the rise and fall of trends and styles were also evident in the kind of films made over the years. By the mid-1960s, many rockers had focused on creating albums instead of singles, a format that allowed them to stretch out and pursue more intricate ideas. Taking it a step further, bands like the Who, the Kinks, and Pink Floyd penned rock operas, and their story lines soon invited film versions with Tommy, Quadrophenia, and Pink Floyd: The Wall. Nor had Broadway failed to notice the appeal of rock operas, particularly the team of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, whose Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita would find their way to the screen in big Hollywood productions, the latter starring Madonna.

Madonna as Evita. Photo via Turner Classic Movies.

Madonna as Evita. Photo via Turner Classic Movies.

The glitz and bombast of most of those projects (sometimes tongue-in-cheek, sometimes not) was echoed in the films of the disco boom. There was nothing bombastic about the surprise blockbuster Saturday Night Fever with its tale of dance-floor redemption in working-class Brooklyn—any film that shoots a scene in a White Castle on Fort Hamilton Parkway certainly has its blue-collar bona fides together. It may not have been a rock and roll movie, but its box-office receipts and massively successful soundtrack album set off a Hollywood stampede in which both the studios and the record labels sought to replicate the formula with music-driven films.

Some, like Grease, were dished up as family fare, while films like Heavy Metal and FM were obviously aimed at adult rock fans. Feeling like ’70s dancefloor updates of AIP’s ’60s beach movies, disco-oriented films like Thank God It’s Friday starring Jeff Goldblum and Donna Summer, Xanadu with Olivia Newton-John, Skatetown, USA with Patrick Swayze, and Roller Boogie with Linda Blair abounded—much to the consternation of some. Director John Landis has described The Blues Brothers, with its veneration of classic soul music and stars including Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and James Brown, as an anti-disco film. Indeed, one of the cameras on the set was emblazoned with “Death to Disco.”

Beyond the disco era, rock films provide a window for viewing the trends and tribes that have defined the music scene at any moment. Led Zeppelin’s 1976 concert film, The Song Remains the Same, was curare to film critics but catnip for the band’s fans and proved a potent title on the midnight movie circuit. But rock films and the whole music scene were moving on: by the end of the decade, Penelope Spheeris’s seminal punk documentary, The Decline of Western Civilization: Part 1, was shining a bright light on the Los Angeles scene—tracking several bands, including Black Flag, the Circle Jerks, X, and the Germs—while New York director Susan Seidelman pondered that city’s downtown punk scene in the sometimes comedic, sometimes tragic Smithereens.

The story of Sex Pistols vocalist Sid Vicious and his partner Nancy Spungen would play like a drugged rock and roll Romeo and Juliet—by turns toxic and romanticized—in Alex Cox’s Sid and Nancy, starring Gary Oldman and Chloe Webb. Each of those films, albeit in a different way, speaks to the complex reactions engendered by the seemingly straightforward punk movement. Beyond the big-name titles, current fans of punk can drop down a rabbit hole of smaller, specialized films, especially when it comes to documentaries regarding regional and local scenes, and even the occasional independent small-budget biopic such as 2007’s What We Do Is Secret about Germs singer Darby Crash.

In England, director Julien Temple kicked off a career that has seen him direct dozens of films on rock beginning with 1980’s Sex Pistols documentary, The Great Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle. Though it never had the same impact on US listeners, the fertile music scene in the city of Manchester was hugely important in the UK, boasting Buzzcocks, Joy Division/New Order, the Smiths, and the Fall during the late ’70s and Oasis, the Stone Roses, and Elbow in later years. Two very good films tell the story of its genesis as a haven for punk and postpunk performers: Twenty-Four Hour Party People, largely focusing on Factory Records, and Control, an affecting biopic on the life and suicide of Joy Division singer and lyricist Ian Curtis.

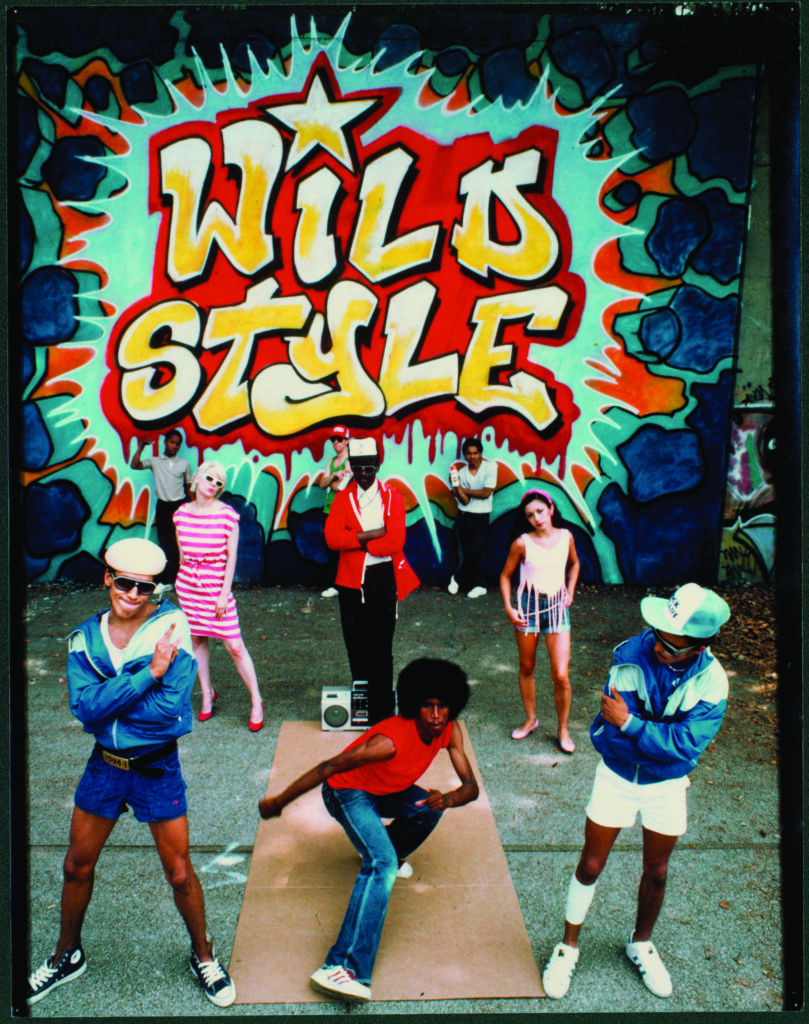

Hip-hop, rap, and emerging Black street culture first came into focus with 1983’s documentary and cult classic Wild Style, still the best treatment of the early days of hip-hop and graffiti art. The next year it had its first commercial hit with the dance-oriented Breakin’, perhaps most remembered now as the film in which Ice-T debuted. Dominated at first by films focusing on the New York hip-hop scene, such as Beat Street, Krush Groove, and Tougher Than Leather, the genre would soon open to include hit films set in Detroit (8 Mile), Memphis (Hustle nd Flow), and Los Angeles (Straight Outta Compton) as well as strong and thoughtful documentaries, particularly the films Scratch, Freestyle: The Art of Rhyme, and Tupac: Resurrection. Humor is an essential part of hip-hop, and if the seemingly inevitable great rap comedy has yet to appear, Chris Rock’s gangsta-rap lampoon, CB4, is a valiant effort (think of it as This Is Spinal Tap meets NWA).

From Wild Style.Photo via Turner Classic Movies.

From Wild Style.Photo via Turner Classic Movies.

For many, rock and the films about it had evolved beyond bands and records to a perspective—a way of being and maybe even finding a community. No filmmaker has expressed that better than Cameron Crowe. “One day you’ll be cool,” Anita (Zoey Deschanel) assures her younger brother, William (Michael Angarano) as she moves out of their home in an early key scene of 2000’s Almost Famous. “Look under your bed—it will set you free.” Hidden there is a satchel filled with wonders: Anita’s album collection. It looks like records by the Rolling Stones, Cream, Led Zeppelin, Joni Mitchell, the Beach Boys, Jimi Hendrix, James Taylor, and the Who, but it’s really the lexicon for a secret language—a language by which William will find his tribe and they will know him. Almost Famous is more than a film about rock as music. It’s a film about rock as consciousness and context, as a way of interpreting and being in the world.

Director Lisa Cholodenko’s Laurel Canyon (2002) also uses rock as a context for discussing values and lifestyles. Jane (Frances McDormand) is a successful record producer, simultaneously hardworking and unapologetically sybaritic and self-indulgent. She also hasn’t been much of a mother to her son Sam (Christian Bale), a newly-minted psychiatrist whose anger is made obvious by his decision to lead a straighter life at odds with her values.

When he and his fiancée, Alex (Kate Beckinsale), a Harvard grad student, come to LA for the summer, they unexpectedly wind up living with Jane in a house that includes her studio and plays host to an ongoing bacchanal of casual sex and soft drugs. Sam is disapproving, but Alex is intrigued, and trouble and soul-searching are soon the result. The film doesn’t address rock as music—we only hear a few snippets of tunes when a band is recording in Jane’s studio—but as a state of mind.

The big tent has also proven wide enough to cover films that lampoon and laud both rock and its artists. The popularity of and critical acclaim for This Is Spinal Tap and Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story might lead you to think the same audience that loves those send-ups will greet the next triumphant rock biopic with a roll of the eyes and an iron grip on the credit card. But judging by the subsequent success of films like Bohemian Rhapsody, Love & Mercy, and Rocketman, you would be wrong.

There’s also a good guy/bad guy dichotomy in how we feel about our populist heroes and, subsequently, in the films that purport to be about rock stars. On one side are the morality plays about corruption and manipulation—films that take their cue from A Face in the Crowd, Elia Kazan’s 1957 tale of Lonesome Rhodes, a guitar-strumming drunken drifter whose folksy charm transforms him first into a popular cracker-barrel philosopher via radio and ultimately into a cynical, power-mad demagogue who turns on his handlers.

Ken Russell’s Fellini-like adaptation of Tommy is such a story, as is British director Peter Watkins’s underappreciated Privilege, a 1967 film about a state-controlled rock star featuring Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones and model Jean Shrimpton. On the other side is the tale of the artist of conscience with his roots in the same plain-clay soil as Lonesome Rhodes, and there the model is Hal Ashby’s magnificent Bound for Glory, the 1976 adaptation of Woody Guthrie’s memoir. If Bob Dylan was the first to tie his reputation to Guthrie’s, albeit briefly, he’s had an army of imitators for whom credibility is intoned like a wedding vow. Beyond Taylor Hackford’s film about Chuck Berry, it’s hard to think of a biopic or documentary sanctioned by an artist or their estate that isn’t about celebrating the integrity of its subject.

More recently, technology has brought a radical expansion of documentary filmmaking, and for rock, that’s meant docs aren’t just about superstars now but cult artists, sidemen, producers, managers, bodyguards, roadies, local scenes, niche movements, and even the secretary who answered the Beatles’ fan mail (2013’s Good Ol’ Freda). The Academy Award–winning documentary Searching for Sugar Man unraveled the mystery of an obscure American performer who became a superstar in South Africa and proved a surprise hit. But sifting through what’s out there can be a daunting task. Occasionally, it unearths a gem.

Like the music that inspired them, these films convey a wealth of images, ideas, and emotions and range from the gleefully mindless to the perplexingly sophisticated.

A portrait of the late sideman Bobby Keys, Every Night’s a Saturday Night, tracing the life and work of the rock saxophonist best known for his decades-long association with the Rolling Stones, flies below most fans’ radars. Keys had a raucous signature sound, but his name isn’t nearly as recognizable as his solos on records like the Stones’ “Brown Sugar” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” and Joe Cocker’s “The Letter,” and the documentary is a good example of a well-researched labor of love. In a genre where crash-and-burn stories occur as frequently as evil spells do in fairy tales, the Keys documentary is still affecting.

Following a hard-partying good ol’ boy from Lubbock, Texas, who became one of Keith Richards’s closest friends but was exiled by Mick Jagger when Keys elected to skip a Stones performance to stay at the hotel and take a champagne bath with a groupie, it’s a classic blinded-by-the-lights story. Yet the high times don’t seem so high and the jokes don’t ring so funny when a bandmate recalls how frequently Keys could pass through a town and mention that an ex-wife lived there. Or when keyboardist Bobby Whitlock, who toured and recorded extensively with Keys as a member of Delaney & Bonnie, pops into a small Texas club to hear his old mate. Expecting a nostalgic reunion, Whitlock is instead greeted with an unsteady gaze and a wave of the finger. “I know you, don’t I?” a burnt-out, severely diminished Keys asks.

From Jesus Christ Superstar. Photo via Turner Classic Movies.

From Jesus Christ Superstar. Photo via Turner Classic Movies.

In the years since Rock Around the Clock first matched images to the music, we’ve witnessed rock’s impact on the world’s greatest filmmakers. In the US, that’s meant some of the best films from our best directors: Martin Scorsese, Oliver Stone, George Lucas, Paul Schrader, Taylor Hackford, Jonathan Demme, John Waters, Penelope Spheeris, Joel and Ethan Coen, Jim Jarmusch, Susan Seidelman, Cameron Crowe, Todd Haynes, Richard Linklater, and Quentin Tarantino, all of whom grew up plugged into the music and thinking about how they could take that attitude and ethos and excitement—that rock and roll sensibility that spoke to them with a power rivaled only by cinema—and turn it into pictures.

The fifty films profiled in Rock on Film, as well as the five interviews with rock filmmakers, are intended to be illuminating rather than definitive. Since the intention is to showcase both crowd-pleasers and buried treasure, the compendium begins with appreciations for the films that most fans see as indispensable, and they constitute a context and yardstick for the films that follow.

The remaining film profiles are intended as a pointedly personal but wide-ranging canon—box-office hits, art-house favorites, documentaries, biopics, and the unfairly obscure—presented in a subjectively curated manner meant to continually underscore the breadth of rock on film. My aim was to mix the serendipity of new discoveries with an added appreciation for familiar favorites while guiding you through the history of rock as seen through the insightful lens of Hollywood and independent filmmakers. Perhaps it will reorient your personal parameters regarding rock on film. I don’t imagine everyone will share my taste and enthusiasm in all fifty cases. I do hope it is the start of an endless quest for previously unknown images and sounds.

Readers may notice that while book includes films on rap, soul, and reggae, none of the now-classic films on country music such as Nashville or Coal Miner’s Daughter are included. Rock certainly owes a debt of origin to country music akin to that owed to rhythm and blues, but in my view, those films were made in an era when country music went out of its way to divorce itself musically and socially from what was happening in rock; indeed, there were moments when it felt as if country wished to declare itself the opposite of rock. (That propensity, thankfully, is now gone.)

One country artist who never felt that way was Johnny Cash, and though it is not included here, the Cash biopic Walk the Line feels like a rock movie to me. In a related vein, jazz trumpeter Miles Davis certainly impacted generations of rock musicians, and Don Cheadle’s film Miles Ahead is worth seeing, but it feels a bridge too far for a rock list. The same cannot be said for rap and a variety of popular Black music. Rock, to me, is an integrated form of Black music, and one that continues to be a vibrant means of expression for many Black musicians. At the same time, rock licks, samples, and references are part and parcel of rap’s musical vocabulary. Rock and other popular forms of Black music have not always traveled the same road, but it certainly looks and sounds like the same destination.

Like the music that inspired them, these films convey a wealth of images, ideas, and emotions and range from the gleefully mindless to the perplexingly sophisticated. But to quote documentarian Les Blank, who devoted his life to peering at musicians through a camera: “Always for pleasure.”

__________________________________________

Excerpted from ROCK ON FILM: The Movies That Rocked the Big Screen by Fred Goodman. Copyright © 2022. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Fred Goodman

Fred Goodman is a former editor at Rolling Stone whose work has appeared in the New York Times and many magazines. His previous books include the award-winning The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-on Collision of Rock and Commerce.