Founding the First English-Language Library in Gaza

Mosab Abu Toha on the Edward Said Public Library

In Gaza, repairing a destroyed house can take several weeks or months. Rebuilding a whole house can take years. That’s because Gaza is under siege, and construction materials enter through Israel. In most cases, construction materials and names of people for whose houses the materials would be used must be approved by the Israelis.

Similarly, any book that’s shipped to Gaza must come through Israel. Almost all packages of books get checked by the authorities at the border. Israel can halt mail service to Gaza any time it wishes, just as had happened in 2016, when the ban lasted for a few months and many of the books shipped for the library initiative I was working on were held hostage on the other side. As a result, some packages arrived in bad condition. I remember that one of the packages contained books donated by Prof. Noam Chomsky.

On August 2, 2014, the Israeli military jets bombed the administration building of the university. The next day, I went to look at the damage. There were only books under the rubble. As I stepped into the English department, a place where I used to meet with my professors and colleagues between lectures, pages of novels and poetry collections were obscured by dust and pierced by shrapnel and splinters of glass and concrete. One fat book, trapped under a bunch of stones and stuffed with dust, was The Norton Anthology of American Literature. I later learnt from a professor at the department that he had made great use of it in preparation for his literary classes.

Carefully lifting the anthology from under the rubble felt like saving the life of a child—a feeling I would experience hundreds of times over the following months, as I succeeded in collecting about 600 books in my house. Our house was not spared from the attacks, either, over the course of those 51 days in 2014. An F-16 bomb razed our neighbor’s house. Big and burning pieces of shrapnel holed up our house walls. We spent the harsh winter months with extra, yet non-closeable, windows. Shrapnel never missed my small book collection. I could hardly recognize the titles, even as books from different parts of the world kept coming in, and more worlds opened in front of me.

Here I am, surrounding myself with dozens of books, closing my room’s door on myself for hours to dispel the noise outside, notably the F-16s and their mock raids.My love for the English language started from an early age. I started learning English at school from the 5th grade (now, in Gaza, students begin learning it in 1st grade or even in pre-K.) It was my favorite subject and I excelled in it. I even got the same grade for English as for Arabic in high school. I then majored in English language at the university and fell in love with the Romantic poets. I’m a person who loves to spend his time alone: I run to nature; I embrace it. Still, regrettably, it seems most of my own songs are witnesses to suffering and wars.

Almost all of the books required for the English courses I studied were photocopied and sold in surrounding bookstores. I don’t recall buying an original copy of a book, whether a novel, poetry collection, short story collection, or a play. Furthermore, a lot of the books in the university’s central library—something like Widener Library at Harvard—are old editions. Libraries here don’t have the ability to update their book collection or obtain new books. That’s all because of the Israeli siege on Gaza, which has been imposed since 2007, crippling Gaza’s economy and social life and the future of younger generations.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2017 that the Edward Said Library opened in North Gaza.

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

Dozens of children and adults visited the library daily, which encouraged me to launch a second fundraising campaign to rent a larger space for the growing collection of books and to purchase more chairs, tables, and bookshelves. Then, in September 2019, a second branch opened in Gaza City. This new branch has a computer lab, where children and adults learn to use computer programs and design websites. It’s become more than a library; arts groups working on music, drama, and painting use the library’s space to rehearse and work together. I never dreamed of starting a library or even being called a “librarian”—it’s a title that was bestowed on me, thanks to the people whose books and money helped me create the first English language library in Gaza.

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

*

In Gaza, each rising sun signals the numerous obstacles that every new day brings, not the least of which are cuts to electricity and shortages of water and cooking gas. Buzzing drones have become part of our daily life, like the sound of sea waves are to a fisherman. There is no sound of train or a Boeing taking off to counter the sound of warplanes and drones. Gaza’s only airport, built in 1998, was closed in 2000. It’s been over 20 years since a Gazan ever watched his country, Palestine, from the sky.

I first travelled outside Gaza in 2019 at the age of 27. I crossed to Cairo, Egypt, and then flew from its international airport to Amman, Jordan. Israel turned down my permit request to travel on a shuttle bus to Amman, a journey which would have taken four hours to drive. Consequently, it took me about two days to arrive at Amman’s Queen Alia Airport and then to the American Embassy. May some would wonder, why not have my visa interview in Palestine? Well, we don’t have any American embassy or consulate in the Gaza Strip. The one in Jerusalem needs an Israeli permit to reach, something I had tried to obtain three times and I miserably failed.

On the road from Gaza to Cairo, I silently kept watching the huge Sinai Desert. I’d never driven in a car for more than an hour in Gaza. Gaza is very small; Egypt is a big country, with new security checkpoints every few miles we advanced in the desert.

I was hoping to make it to Cambridge, MA, in time for my fellowship program at Harvard University. My fellowship as a research scholar was scheduled to begin on Sept. 1, 2019. However, once I arrived in Amman on Sept. 5, 2019 and made it to the U.S. embassy there, the visa officer didn’t issue my visa nor deny it. Rather, I was asked to submit information about my family, details about my parents and siblings, addresses I lived in during the previous 15 years, all email addresses and phone numbers I used in the past 5 years. I was suspended in Jordan for about 40 days: away from my home and family in Gaza, yet being unable to return and be with them. Then, after it was approved, I finally landed in Boston on October 18, 2019 to start a fellowship in the Department of Comparative Literature at Harvard University as a visiting poet and Houghton Library as a visiting librarian in residence.

Once in the States, it took me a few days, and even weeks, before I realized how big the world is. Travelling within America was like travelling between oceans and continents to me. The siege and occupation that Israel maintains in Gaza (and the West Bank) has limited our ability to imagine how diverse and geographically spacious the world is.

Upon returning to Gaza in February 2021, I started to reflect more deeply on my journey to the States, in relation to places and people, animals and birds, and the whole landscape. It’s never easy for a person living in Gaza to focus on one thing for a good period of time. But here I am, surrounding myself with dozens of books, closing my room’s door on myself for hours to dispel the noise outside, notably the F-16s and their mock raids, in addition to the surveillance drones and their bothersome whirring during the night and day (and from time to time, gunfire from Israeli boats and warships).

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

In Cairo, and before I traveled to Amman, the taxi had dropped me in a busy street. I still don’t know its name. I only spent 13 hours in Cairo, mostly sleeping and resting at night after the long and hectic drive in the desert. At night, a terrible sound cut through the sky. It was an airplane taking off from Cairo International Airport. I looked around me; not a single person paid attention to the plane or sound. It was only me, a young man hearing the engines of an airplane, not an F-16, for the first time in life.

Three months following my return home, Israel launched another horrific series of attacks on Gaza. The aggression lasted for 11 days, claiming the lives of 260 people, of whom 66 were children and 40 women.

I lived in horror, along with my wife and three children, every single minute. My writing again became concerned with death and the horror of war. Horror of parents and their children, horror of birds flying aimlessly after every explosion, horror of trees when dust shroud their fruit and flowers.

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

Photo via Mosab Abu Toha

My debut poetry collection is out in the free world, though it got stuck for a few days in the West Bank, simply because UPS couldn’t deliver to Gaza. I had to find someone who could collect the five copies of my book in Ramallah and carry them with him to Gaza. Now that my book is taking its own path out there, I keep thinking about how I can, one day, author a book that’s more hopeful, a book that my under-six-year-old children can read and enjoy when they grow up.

__________________________________

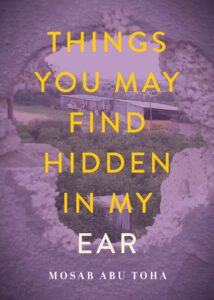

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza by Mosab Abu Toha is available via City Lights.