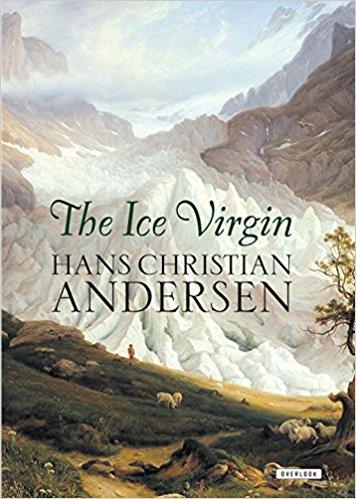

For the First Time On Its Own, Hans Christian Andersen's Adult Novel

You Definitely Do Not Want to Mess with The Ice Virgin

Although best known for his children’s stories and fairy tales—including such classics as Thumbelina and The Little Mermaid—Hans Christian Andersen was a prolific writer of lesser-known works for adults as well; his oeuvre includes novels, plays, travelogues, and autobiographies. The following is from his short novel The Ice Virgin, which is now available as a stand-alone, modern English language edition for the first time, translated Paul Binding.

*

Rudy left Bex for home, taking the high mountain route for the sake of the fresh, cooling air—up where the snow lay, where the Ice Virgin reigned. The deciduous trees stood far below as if they were mere potato-tops, fir and shrubs became smaller in size, the Alpine roses grew close to the snow which lay in isolated patches like pieces of linen being bleached. A single blue gentian stood its ground; Rudy smashed it with his rifle.

Higher up two chamois came in sight. Rudy’s eyes lit up, his thoughts took off in a new direction. But he was not near enough to take an accurate shot. He climbed higher still, to where only a rough type of grass was growing between the boulders. The chamois went in peace onto the snowfield. Rudy hurried along eagerly. The cloud banks were getting lower all round him, and all of a sudden he found himself in front of a precipitous rock-wall just as the rain began to pour down.

He felt a scorching thirst, heat in his head and coldness in his other limbs. He grasped his hunter’s flask, but it was empty; he hadn’t thought of that when he charged up into the mountains. He had never been ill, but now he had a kind of taste of what it was like. He was done in, he felt a longing to fling himself down and go to sleep, but everything was streaming with water. He tried to pull himself together. Objects were quivering most peculiarly before his eyes, but suddenly he saw what he had never seen here before, a little house recently carpentered together and leaning against the rock-wall. And in the doorway stood a young girl. He thought it was the schoolmaster’s Annette whom he had once kissed at the dance, but it was not Annette, and yet he had seen her before, possibly near Grindelwald that evening he’d made his way home from the shooting contest at Interlaken.

“However have you got here?” he asked.

“I’m at my home,” she said, “I’m looking after my herd.”

“Your herd—and where does it graze? Up here’s only snow and rocks.”

“What a lot you know!” she said, laughing. “Below the surface here, only a little way down, there’s delicious grass. That’s where my goats go! I never lose a single one of them. What’s mine stays mine!”

“You’re a bold one!” said Rudy. “You are too!” she replied.

“If you’ve got any milk, spare me some! I’m intolerably thirsty.”

“I’ve got something better than milk,” she said, “and you shall have some of it. Yesterday some travelers came up here with their guides. They left behind half a flask of wine the like of which you’ll never ever have tasted. They are not coming back for it, I am not going to drink it—so you’ve got to drink it!”

And she brought out the wine, poured it into a wooden cup and gave it to Rudy.

“It’s good!” he said, “I’ve never tasted such warming, such fiery wine!” And his eyes sparkled. A renewal of life, a glow came over him, as if sorrows and burdens were evaporating. Bubbling, vital human nature was stirring in him.

“But it really must be the schoolmaster’s Annette!” he exclaimed. “Give me a kiss!”

“Yes, all right, but give me the beautiful ring you’re wearing on your finger!”

“My engagement ring?”

“Exactly that!” said the girl, pouring wine into the wooden cup and putting it to his lips, and he drank. Happiness in being alive coursed through his blood; the whole world was his, he felt, why worry oneself further? Everything exists for our enjoyment and to make us happy. The stream of life is the stream of happiness. To be carried along by it, to permit oneself to be carried along by it, that is what bliss means. Rudy looked at the young girl; it was Annette and yet it was not Annette, still less was it the troll apparition, as he’d called her, whom he’d encountered near Grindelwald. The girl on the mountain here was as pure as new-fallen snow, full as an Alpine rose, and light as a young chamois, yet basically made from Adam’s rib, as human as Rudy. And he flung his arms round her, and gazed into her wondrous clear eyes. It was only for a second, and in this time—yes, explain it, make a narrative of it, put it into words for us all—was it the life of the spirit or of death that filled him? Was he raised up or did he sink down into the deep, deadly ice chasm, deeper, ever deeper?

He saw walls of ice like blue-green glass; endless gullies opened all round him, and the water drip-dropped ringing out like a carillon, and yet also clear as pearls shining in blue-white flames. The Ice Virgin gave him a kiss, which made him shiver through every bone in his head. He gave a cry of pain, wrenched himself free, stumbled and fell. It became night before his eyes, yet open them again he did. Evil powers had come to the end of their game.

The Alpine girl had vanished, gone away from the hut that had been sheltering her. Water streamed down the bare rock-wall, snow lay all round, Rudy was shaking with cold, soaked to the skin—and his ring had disappeared, the engagement ring Babette had given him. His rifle lay in the snow beside him; he picked it up and tried to shoot from it, but misfired. Rain-clouds lay inside the ravine like firm masses of snow. Her Dizziness was sitting there, enticing guileless prey, and beneath her there came a ringing noise in the chasm as if a boulder were falling, crushing and annihilating whatever stood in the way of its descent.

But in the mill Babette sat and wept. Rudy had not been there for six days. He who had done her such an injustice, he who should be extending both hands for forgiveness, because she loved him with all her heart.

__________________________________

From The Ice Virgin, by Hans Christian Andersen, courtesy The Overlook Press (trans. Paul Binding). Translation © Paul Binding 2016. Feature image, Landscape of the Alps, by Ferdinand Hodler.

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen is the legendary and beloved author of such children's classics as The Little Mermaid and The Ugly Duckling.