For an Echodeviant Poet, Mishearing is a Method

Noa Micaela Fields on the Changeable Power of Language

For years I sang, unknowingly and uncorrected until one karaoke night, my own made up version of Rihanna: “We found love in a whole new place.” There’s a word for wrong lyrics like these, they’re called mondegreens—a name which originates in mishearing. The novelist Sylvia Wright coined the phrase after conjuring a “Lady Mondegreen” out of the line “laid him on the green” in a Scottish ballad her mother read aloud to her as a child. In a whimsical article for Harper’s, she insisted that mondegreens were not merely mistakes, but “better than the original.” Hearing loss need not be a loss, I’ve found and have come to love how mishearing alters me.

I am a trans poet with hearing aids, and I playfully call myself an echodeviant as a way of reclaiming mishearing. (“Echodeviant” is a riff on CA Conrad’s Ecodeviance, a genderexpansive collection of max-embodied poems and grief ritual-prompts, willing to “do everything wrong just once” if it might “carry us away forever.”)

The burden of communication is all too often placed on deaf or hard of hearing people to seek clarification or guarantee accessibility in oral settings.

“Please excuse that very inventive Ms. Hearing,” Rachel Kolb recounts her disabled grad school advisor’s voice-to-type emails with often hilarious autocorrections. In her deaf memoir of voice Articulate, Kolb’s frustrations in learning to navigate speaking and signing worlds lead her to an understanding of language as “fumbling and shape-shifting, addressing a different living being and trying to pass through the layers that separate us.”

The burden of communication is all too often placed on deaf or hard of hearing people to seek clarification or guarantee accessibility in oral settings. Another new deaf memoir, The Quiet Ear by British poet Raymond Antrobus, declares mishearings a “staple of deaf poetics, a way to honor one’s own sound.” Mishearing, as a point of departure, sets the stage for mischievous rewriting: by hearing otherwise, we can mark ourselves here, in a world of our own. “Draw me the song that sings the sky stifled,” Deaf poet Meg Day writes synaesthetically in Last Psalm at Sea Level (the first poetry book I ever read that mentioned hearing aids) in response to Clayton Valli’s ASL poem “Deaf World.”

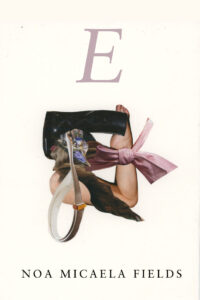

In the spirit of accessible world-making, my debut poetry collection E (Nightboat Books) alchemizes mishearing into a political possibility of glitch, glamor, and noncompliance. Like a whisper-free game of telephone, my poems pass on a queercrip legacy of subversion. Here’s the opening poem from my book, an ars poetica called Homophonic, Trans Later:

At the edge of hearing atmospheric strings

Not a blank space Möbius strip

Between sentences beginner’s mindset

My captionless life mea culpa

What did I miss wander off-script

Too embarrassed to ask dare embellishment

Can you repeat that change of scenery

Say again stray away

I speculate spectrally isolated specks

Consider possibilities conspiratorial syllables

Ear transposes interrupting

Jumbled syntax chamber music

Risking wrong notes whistle one-way

Periphery’s poetry parallel play

From other words form other worlds

My poem title plays on homophonic translation, a form of translation prioritizing reproducing the original poem’s sound and mouthfeel rather than its meaning. In “A,” a long serial poem of his life in 24 movements, Louis Zukofsky incorporates passages re-rendering poems by Catullus and from the Book of Job, among other sources. Upon reading I was struck by the musicality of this interplay across languages and latched onto the somatic rippling of sound’s physical transformation, which captured something of my experience of mishearing and also hormonal transition.

As trans scholar micha cárdenas writes in Poetic Operations, “Shifting is a process of experimenting with the malleability of reality by moving in collaboration with the lively matter which bodies are composed of.” Language, of course, is lively matter too, a body open to recomposition. This flux is trans. So I decided in my book to reclaim Zukofsky’s method to mishear fragments from“A” into E—transposing his verse up a fifth into the key of estrogen to sing, filthy muses, the catabasis of my transition.

Using language “inappropriately” excites me.

My introduction to homophonic translation came from my former teacher, Mónica de la Torre. In her book Repetition Nineteen, she creatively plays with unreliable self-translation and deliberate mistranslation at the borders of English and Spanish, emphasizing what’s not interchangeable in apparent equivalences, as in the case of “false friends.” Misunderstandings spring rhizomatically in the cracks of bilingual code-switching and raise issues of access, speculation, and collaboration in the process of translation. Taking a myriad of approaches to revisiting and translating her own poem Equivalencias from the nineties, she teases through, “How to tell apart what is signal and what is noise when the resonances of both languages are equally loud?”

The poets Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino’s posthumously published dialogue Hearing investigates what it means to listen, especially as sound outruns language as a “continual conceptual rebellion.” As a point of departure, the authors set a rule that they would work in reference to “a sound (or sounds) actually heard or being heard during the composition,” and these source sounds accrue as they are passed back and forth, stacking homophonic clusters like rudder/udder/utter/other in layered associations as they tune and attune their poetic voices in echo.

What I find compelling about their collaborative experiment is the music of its mutating thinking through listening’s elusiveness and faultiness to interpretation. “When things are heard, they are vulnerable.”

Using language “inappropriately” excites me. Hard of hearing scholar Michael Davidson writes in his book Distressing Language, “a poetics of error is both ecstatic and dangerous, creating art by speaking out of turn.” As Legacy Russell writes in Glitch Feminism, “Glitch is a form of refusal.” Like her, I want to “celebrate failure as a generative force, a new way to take on the world.” When in Minor Feelings Cathy Park Hong proclaims “bad English is my heritage. I share a literary lineage with writers who make the un-mastering of English their rallying cry—who queer it, twerk it, hack it, Calibanize it, other it by hijacking English and warping it to a fugitive tongue.”

One of my favorite poetry collections in recent memory is JJJerome Ellis’s Asters of Ceremonies, which renames their stutter an instrument. The title is pointedly not “master”—the dropped constant emphasizing that the art of stuttering isn’t too hard to aster. Through music and ceremony, Ellis gives notice to dysfluency as a source, as a vessel, as a gift.

This healed years of speech therapy humiliation rites I experienced as a kid—being pulled out of class for enunciation exercises and other torturous games that drilled into my head that my speech was broken, with impediments that I needed to master in order to fit in and be understood. I experience the spaciousness between words on the page and in Ellis’s performances as freedom: permission to get lost and revel in crip time, to listen deeper and notice the porousness of speech and music.

In the variegated company of mishearings, increasingly I’ve come to feel that missed sound is an invitation into generative confusion as an alternative conclusion. To claim mishearing as my method is to discern a remixed syllabary of emergence amidst the hiss, feedback, and glitch of my hearing aids. It is to heed my own voice, and above all else, heal.

__________________________________

E by Noa Micaela Fields is available from Nightboat Books.

Noa Micaela Fields

Noa Micaela Fields is an echodeviant (trans poet with hearing aids). E is her first book. She lives in Chicago. www.noamicaelafields.com