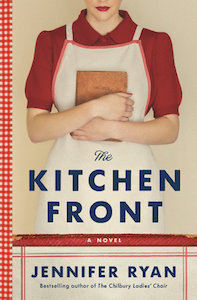

Food is Love: Weaving Together World War II History and Family Recipes

Jennifer Ryan on the Making of Her Novel The Kitchen Front

The toasty scent of hot scones, blackcurrant jam bubbling in the pot, my bare feet on the cold stone kitchen floor, my grandmother bustling about in her floral apron: These were the hallmarks of my childhood. On the table were ingredients from the past: lard, Spam, liver, and a box of dried egg powder. Britain came out of the war in 1945, but it wasn’t until 1954 that food rationing was lifted. My cheery grandmother was a product of that era; her pies and puddings, soups and gravies, were all formulated with a set of food restrictions that made her cooking at once ingenious and warming. To me, every one of her dishes was full to the brim with history: the nation’s, my family’s, my own.

It was my grandmother who inspired me to write about the Second World War with her stories of that era. One of them involved rearing a pig in the backyard. In another, she painted her legs with gravy due to the stocking shortage only to have the neighbor’s dog chase her, desperate to lick her legs. One of her favorites—how she was part of a tone-deaf choir that became all-women only after the men left for war—inspired my first novel, The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir.

“We nourish who we love,” she would tell us. Every dish she made was an act of love, and all those smells, tastes, and textures brought the world in which she had lived back to life: the bombs, the destroyed homes, the shortages, the sexual freedom, and the new opportunities for women. Her stories had them all.

This aspect of her life, and its potential for exploration in a novel, was always in the back of my mind. Cooking was so central to women’s lives that when food rationing and shortages began in 1940, a revolution of sorts changed the very foundation of the way women found and prepared food. At the same time, women were becoming more independent, earning their own money, and finding more agency with the men away. Cooking and food were in the mix of the many ways women took control.

A novel was in the making.

1.

Take one old, weather-worn recipe book.

My grandmother’s recipe book was my first port of call. Its brown binding, battered by decades of splatters and subsequent wipes clean, was coming loose from its frayed spine. Its bulging interior was packed with extra pages, leaflets, and cutouts from magazines and newspapers. Its pages were covered with her scraggly handwriting, upper and lower case infused, spelling optional. Around each recipe were small corrections or additions, often written in pencil or a different pen, showing the evolution of each recipe as it became perfected.

At the front of the book, there was a different handwriting: softer, more slanted. After some family discussion, we worked out that this would have been her mother’s book before it was my grandmother’s. It was a family heirloom more precious than her best china, more meaningful than her jewelry. I borrowed the recipes, tried them, merged them into my new story.

2.

Take a pile of government leaflets.

The National Archives is a grand building in the leafy London suburb of Kew. A cross between a giant library and a Secret Service headquarters, it was reverently silent as I passed up the stairs, passport in hand, to fill in a request, have my photograph taken, wait for it to be processed—or background checked for espionage activities—before being issued a photocard. Armed security staff checked the few belongings I was allowed to carry in before an electronic gate allowed me access to the inner sanctum.

While I waited for the files, I watched the compulsory video about handling the original documents. Wear the white gloves provided. Use white fabric-covered weighted strings to hold books open rather than your hands. Never mark anything—you will be frisked for pens as you enter the building. A strict pencil-only policy is rigorously maintained.

I took my pile of folders to a desk and dove into the past, momentarily baffled by the first leaflet beholding a recipe for Sheep’s Head Roll. The Ministry of Food produced prolific leaflets during the war. The nation’s spirit needed to be kept up, and one this was for certain: Nothing would bring the nation to its knees faster than poor nutrition and a disheartened, hungry population. Painstaking effort was required to get the nation’s housewives and cooks on board.

Most of the leaflets instructed women about nutrition and how to cook a balanced meal. Others focused on cooking with an abundance of potatoes and home-grown vegetables, and where to find protein when there was no meat. Oatmeal was a favorite, and there were tips for adding it to everything and anything, from pastries and breads to white sauces and pie fillings. The Ministry of Food ran “Let’s Talk About Food” and “Food Facts,” series of advertisements, in women’s magazines and newspapers. Slightly bossy in tone, they told people about new rations, easy recipes, and while they were about it, they had a quick scold about saving fuel and not wasting potato peels.

“We nourish who we love,” she would tell us.

The rationing details, wartime recipes, and cooking tips I garnered from the archives provided the historical foundation for the rest of my research. I turned to other books on the topic, too. Spuds, Spam and Eating for Victory by Katherine Knight becomes my mainstay, taking pride of place on my desk. The Wartime Kitchen and Garden by Jennifer Davies takes a close second. Home economist Marguerite Patten’s books provided some wonderful recipes and cooking tips. The View from the Corner Shop by Kathleen Hey was handy for understanding how shortages and rations worked on a day-to-day basis. The Taste of War by Lizzie Collingham covers the politics behind rations, including scams, the black market, and policing the policies.

3.

Take one radio show.

“The Kitchen Front” was broadcast on the BBC every morning during the war. A product of Ministry of Food propaganda, it was aimed at cooks and housewives, explaining food rations and inspiring them with recipes and tips to help with the cooks’ perennial problems: the lack of meat, cooking fats, dairy, and sugar.

The show initially featured a male presenter who was previously a travel show host, and after it became clear that the mostly-female listeners were uninspired, female hosts took the lead. One of these was Ministry of Food home economist Marguerite Patten, while others included cookery writers, chefs, manor house cooks, a housewife, and comedians Elsie and Doris Waters.

In my research, it was not clear how female presenters were chosen. I decided to base my novel on a cooking competition, the prize of which would be the job of co-host for this show. A contest would give me the opportunity to showcase both the problems cooks faced amid rationing and the ingenious recipes that were the result.

Competitions were all the rage in World War II-era Britain. They were free of charge, could be held in every church hall, and diverted participants and audiences from the horrors of war. Uplifting newspaper headlines with photographs of choir contestants, talent shows, and fundraisers appeared across the country. Local food competitions were always popular, featuring everything from the tastiest jams to the biggest turnips and best wartime recipes.

I decided my cooking contest would have four women contestants, each of them professional cooks. One is a young widow desperately trying to keep a roof over her children’s head with her home baking business. Her sister, married to a businessman, is a Ministry of Food home economist, demonstrating wartime recipes in town halls. The third contestant, a professional chef conscripted to lead a factory canteen, is desperately concealing an unwanted pregnancy. The final one is a young kitchen maid who yearns for freedom.

The contest has three rounds, dividing the book into three parts: Starters, Main Course, and Dessert, consisting of 12 recipes in total.

4.

Add a sprinkle of stories.

The interviews I carried out with those who had lived through the war brought a wealth of recipes and cooking tips, as well as intriguing, funny, and heartbreaking stories. Everyone who was there had something to say about it, from the dullness of potato pie to breeding rabbits and the putrid stench of whale meat.

In particular, the Mass Observation project brought a wealth of women’s voices to my research. The sociologists who led the effort encouraged people to write journals and send them to their research center where some would be published in a newsletter. The rest were used by the Ministry of Information as a gauge for their propaganda measures. By the end of the war, over 5,000 people had sent in their daily happenings and musings. The originals can now be viewed in the University of Sussex Archive, and many are published in books. These, as well as published letters and memoirs, provided a fascinating insight into the challenges of finding, buying, and cooking food.

5.

Taste.

The warming smell of hot scones wafts through the kitchen as my daughter and I taste the sharp sweetness of the bubbling blackcurrant jam. I am instantly transported to my childhood home: my grandmother in her apron, her recipe book open on the table. I am both there and here, a link between the past and the future, the cooking a legacy passing through me from one generation to another.

Cooking, like writing, isn’t only about the craft or the careful mixing of textures and sensations. It is also about where we have come from and where we belong. It is about who taught us along the way, who nourished us, and whom we nourish in return.

__________________________________

The Kitchen Front is available from Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2021 by Jennifer Ryan.

Jennifer Ryan

Jennifer Ryan is the author of national bestseller The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir and The Spies of Shilling Lane. She moved from London to Washington, DC after marrying, and she now lives in Northern Virginia with her husband and two children. Her forthcoming novel, The Kitchen Front, is about a wartime cooking contest, complete with wartime recipes.