Flyover and Proud: TaraShea Nesbit Reckons With Home

Because Sometimes the Floor Needs Swept

The first time I heard the phrase “flyover country” was in graduate school, in a Midwestern city, and the person explaining the phrase was telling me a bit of gossip. A faculty member, it was rumored, might not get tenure, because her book was published on a flyover press.

Flyover? I asked.

It was after a reading from a visiting writer, who wore a velvet blazer, brought to us from a university near a coast, surely, as they often were. I would have had a small plate in my hand of things I’d never eaten before that year: triple cream brie, those thin crackers you spread fancy cheese on, and in my other hand, red wine. My new weekly, free, dinner, especially useful at the end of the month, before our stipends came in.

Like in ‘flyover country’? she said.

I cocked my head.

She explained.

Not a more prestigious, New York press, but a university press located in the Midwest.

Where I’d lived my first 23 years, Ohio, was a place never to land, a place to dismiss for a better elsewhere. I’d wanted to dismiss it, too, as soon as I learned there was an elsewhere. New York was the fixation of my ambition—although how it became that is difficult to place. In high school, I requested college brochures on a dial-up computer connection in my father’s unheated den. Barnard was the school I most wanted to go to because I suspected I was queer. But I chose the state school, instead, persuaded by my father not to acquire much in student loans. After graduation, I worked in an optical shop and nearly made the mistake of getting married at 22, before I left for graduate school in St. Louis.

*

At school, I submitted a poem for workshop with the line, The floor needs swept. The famous poet leading the workshop said there was something wrong with that phrase.

Could I read it aloud?

I read it aloud.

Don’t you hear that? he asked.

When I showed no recognition of my mistake, he explained. He passed his copy of my poem to me, which had “to be” written between “needs” and “swept.” I studied it, considered it, but did not “fix” it. That is how we speak here, in Ohio, if you are from certain regions. Sometimes, the floor needs swept.

*

A year after graduation, a friend and I crossed the west, and on our way to Seattle—the farthest place I could get from my family and still be in this country—I met the person I later married, in a gold mining town in Nevada. We moved to Seattle, then Tacoma, then Denver, then Boulder. Ten years passed. I thought I’d done it; I’d forever outgrown the Midwest.

I got pregnant, I birthed a full-term daughter, who was born unbreathing, we grieved, I published a novel, I finished a PhD, I went on the academic job market, and I was pregnant again. A school in the Ohio valley of my youth, with a coveted 2-2 teaching load, health insurance, and a 10 percent matching 401K, was hiring. I brought my husband and our five-week-old on the on-campus interview. My husband was surprised that the pizza place did not know what Kalamata olives were. I knew this place, these people. I was offered the job.

With a seven-month-old and a western husband that confused the geographic location of Ohio with Illinois, I moved back to the Miami Valley, back to where my entire family—mom, dad, brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles, grandparents—live. I was ecstatic to have a job, but the first year was also a mourning process I did mostly privately, for how unsavory, ungrateful, and insulting it is to tell someone living where you live that you are mourning living there.

*

That was four and a half years ago. Before I moved back to the Midwest, I’d stopped seeing any good in where I came from, if I ever saw good. I did see good there once. Riding in the back of the pickup on our way to a family reunion at Miller’s Grove, that was a good memory, with my closest cousin, Jessica, four years older, as our grandmother drove. Jessica liked to look through our grandmother’s large J.C. Penny’s catalogs and pick out items for her future baby’s nursery. I liked to pick out business suits I’d wear to my nebulous “professional” job. Jessica died from complications of addiction the year I moved back to Ohio. That is one way to frame it. Or she died from grief, from loneliness, from poverty, from childhood sexual abuse, from a lineage she could not escape, because she was more loyal than I, I sometimes think. Because she wanted and needed her family, I sometimes think, whereas I had worked myself into needing nothing, and left.

*

A friend I made in Denver flew in from New York City to give a reading. I was apologetic through the cornfields. I asked her which version of mediocre she’d like to have for dinner: Indian, Asian, American.

She laughed.

She loved New York. It reflects the way I experience life. Messy and chaotic.

I drove us past the tawny winter fields, the houses on acre lots with man-made ponds, across train tracks, a strip mall.

This place resembles life for me, I told her. There is nothing and then you die.

I qualified: I mean, the distractions are few here from mortality, or at least the distractions that would be most distracting to me: art openings, museums, book launch parties. Privately, I also think I’m spending more time with my children then I would if I lived elsewhere: we bake muffins, we go to the park, we spend many hours reading books.

There is nothing and then you die, I said, again, lightly, and she laughed.

*

Given the options for shopping within 45 miles—a TJ Maxx, a Walmart, and a Goodwill full of clothes from the TJ Maxx and Walmart—as well as a busy teaching schedule and two small children, I don’t drive into the city (Cincinnati) to shop for clothes, or get my glasses adjusted, or wax my eyebrows, and the clothes I order online are quick purchases, often ill-fitting, and get returned, or linger too long in my closest, unreturned, until I have to keep them because the return period has expired. So, I dress like I’m from here, too—nothing from an independent designer, no whimsical shoe from a boutique on Pike or Pine in Seattle. Those days are, if not gone, dormant, buried beneath the fallen maple leaves of my life. This is how one grows into Midwestern, I think, but perhaps this is just how one grows older, making calculations, valuing time over appearance.

She died from grief, from loneliness, from poverty, from childhood sexual abuse, from a lineage she could not escape, because she was more loyal than I.A small town asks you to be a little more decent. Our friends who moved here from Brooklyn say they learned quickly not to display road rage—that person you flipped off could easily be the person in front of you in preschool pickup, at the grocery store.

I was writing at the coffee shop when someone put their hands on both my shoulders. I turned to see not a threat, as I had anticipated, but a professor and friend who has started writing personal essays. She has good news: her newest essay will be published soon. We celebrate for a moment and discuss our kids and a visiting scholar’s talk—a conversation both of us would be having at any university. My friend was an undergrad at Barnard the years I would have been there. It is entirely possible I would have found myself here, back in the Miami Valley, had I lived those years in New York. I could have ended up exactly where I am. Except if it had happened that way, I might presently owe more money in student loans than we do on our mortgage.

The goal of a teaching job with a 2-2 load in an affordable, reasonably-sized west coast or mountain town where we have friends, or family, grows fainter and fainter. I like my colleagues and I like the students here. I understand the subtlety; the small cues that suggest a lot more is going on beneath niceness. Our shared geographical upbringing does, more than I thought it would, give us connection, and I have a particular tenderness for students who come from lineages closest to my own. Last week I taught Joan Didion’s “Goodbye to All That,” and my students said that the essay worries them. They fear they’ll one day feel the way the narrator does. Most of them are from this region. We discuss how Didion downplays that leaving New York is also returning to where she is from, California. It’s shameful to return to where you are from, one student says, and others nod. It’s the last thing they want to do right now.

My dad used to say, upon his friends asking about me, my lapsed visits, all the holidays and birthdays I missed, I knew I raised my daughter right if she never came back.

Many of my family members are in recovery. The automobile factory my grandfather worked at has closed, and with it, other factories my family members have worked at, and the associated correlations with unemployment and opioid addiction are palpable. But I know that more from my friend who is an ER doctor than how I once did as a child, scared and confused watching a caregiver nod off. My fantasies are no longer to live in a loft in New York—I know what kind of lineage I’d need, or what kind of risktaker I’d need to be, to live that way. Now my fantasies are that a small cottage adjacent to our house will come on the market, and my mother will buy it, or we’ll help her buy it. My mother, who is looking to buy a home again, after losing hers to bankruptcy when I was in college, told my daughter that her ideal home is next door to us and after school, my daughter comes to her house for a snack. I can see the possibility of comfort in this.

My father used to say, “I knew I raised my daughter right if she never came back.”On certain spring afternoons though, a Friday after teaching, when the sun shines as I bike home, I could admire the crocus and daffodils pushing through hard clay. But often, I wish for a back patio in a city to meet friends in. I wish for a bookstore. I miss watching fiddlehead ferns unfurl along the trails of the Pacific Northwest. I seek a little lapse in being aware of my mortality.

But perhaps there is something else I’m reckoning with here. As a child, ambition was my survival skill. If a parent was shooting up, if a pedophile was targeting me, if I knew what bar to call to find my other parent, until I didn’t and they were gone for a week—I studied, I practiced basketball, I wrote. I trained my mind to imagine a future where happiness resided. Happiness, I thought, was elsewhere. But elsewhere, it turns out, was not necessarily geography. The pattern of my thinking—when stressed I catapult out of the present and plan the future—was an important survival strategy I’m trying to unwire.

When people ask about my family and I pause too long for social comfort, my husband offers, She was raised by wolves. But I don’t blame the wolves. Before them were their mothers and fathers, their mothers’ mothers and fathers, and to all of them, poverty and trauma.

*

I want surprise and delight, I tell my husband, when I get home, sulking in a way he has little sympathy for, which is a trait I mostly appreciate about him. We push the strollers to the ice cream shop and stop to watch the tadpoles flitting about in the creek.

I have never called this place flyover country.

*

The floors need swept, I say sometimes, of this daily mess that is two children eating dinner. I say it if I am tired, if I’ve forgotten, or if I’m choosing to teasingly offend my husband. I wonder what our two children will say, if they will drop “to be”, if they will say “soda” or “pop”, what they will choose to identify with, to hide, when they begin to see and hopefully question the implications of these differences. She’s done it once, our daughter.

Mom, she said, my dress needs washed.

What did you say? her father asked, smiling. He had heard her.

To my surprise, it gave me great delight.

__________________________________

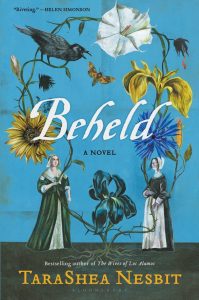

TaraShea Nesbit’s, Beheld will be available on March 17 from Bloomsbury Publishing.