This is not a confession.

It is not even an explanation.

I know I was a bad mother to you. That’s why I’m here, in the place for bad mothers whose daughters have forgotten about them. Now, don’t make that face. I know you haven’t forgotten me. But you don’t know what it’s like here, paralyzed by time, when all there is to do is think of all the ways I have failed you, all the stories you don’t know, all the reasons I had, or thought I had. All I have here is time to think, time to replay the events of my life, to undo somehow our estrangement, make things turn out better, change what happened between us.

I suppose it is an unburdening.

That’s all I want, to be free of the burden of all this time. Time is slow here, in this place. Minutes take hours, hours unspool with silent inevitability, and days are blank eternities as I think about what I want to say to you.

Back when I played piano, I used to imagine I was free from time, that I was able to float through time as I played. But performing comes with its own burden: the burden of omniscience. Of knowing exactly how a piece is to be played.

And yet, isn’t that the trick? To play a piece of music as though the inevitable is actually a surprise? When I performed, I was a fortune-teller, an illusionist, a guide. And yet I know there was some part of me hoping that I, too, might be led someplace unexpected, that there may have been something yet I didn’t know.

But now, here in this place, unable to play, I am no longer all-knowing, and without the omniscience of a performer, I can only guess at whether I am doing the right thing in telling you all this. Perhaps this moment, here, right now, is precisely where I am supposed to be, precisely where I was meant to be led: here, leaden, no longer able to float. Perhaps this is what I deserve.

I don’t blame you. I know this place is a practicality, not a punishment.

Where else would I go?

My wrists ache as I sit here, empty of music, full of time.

So. You discovered the paintings. You learned about your father. And now I need you to know what I know as I know it now, bereft of omniscience but cursed with time to think, so you can understand it all. To understand me, finally.

Note that I did not say forgive.

*

In the early days in the hospital, I kept my eyes closed. Especially when he was there. I didn’t need to see Mor to sense his presence. I could smell the mix of turpentine and sweat on his coat. I could hear his impatient sighs, the repetitive clearing of his throat, his constant, nervous readjusting in the vinyl hospital chair. He was never able to keep still.

This was 1933, before you were born, before I was married to Samuel, back when I was married to Mor.

It’s easier than you might think to not respond, to stay in the dark, dreaming. When your eyes are closed, time passes without you. You hover in suspension. Darkness. Endlessness.

I kept my eyes closed for the doctors, too, at the beginning, but eventually it became easier to give in, open my eyes to shut their mouths. They promised me that if I tried for them, if I opened my eyes, I would be able to play. I had seen a battered upright in the common room. They promised me if I answered their questions and kept my eyes open and stopped trying to slip away, I would be able to play it. They told me I was there because I had tried to slip away. They told me why I was there, but not how. The facts of what had supposedly happened, but not anything that made sense to me at the time. My wrists throbbed inside their bandages, a message from the past.

I couldn’t open my eyes when Mor was there. I listened to him fidget and sigh, and I tried to stay very still, still enough to disappear, until I fell asleep and, finally, he was gone.

Once, when he returned, I felt a hand on my hand, and for a tense moment I thought it was him, but it felt at once too gentle and too confident. Then the light above me was adjusted and a cool towel was placed on my forehead, and I realized it was a nurse, changing my dressings.

When I felt the slight rush of air as the nurse moved away, I opened one eye just the slightest bit, and I saw him, his profile contorted with concern, his posture tense and anxious as he watched the nurse leaving. I had the impulse to comfort him. I remember thinking that if his face were a key signature, it would be C-sharp major, so many worried hatch-marks crowding the staff.

But as he turned to me, I was overcome. I immediately shut my eyes. I couldn’t look at him. I didn’t want him to see my eyes opened. I turned my head away from him, turning my body as much as I could given the restraints on my ankles, my wrists. I lay there, feeling my heart panicking in my throat, my skin cold and clammy, my hands shaking. I tried to breathe, to slow the sharp, spiky inhalations before they became cries, hurt my throat, alerted someone.

The treatments they gave me made me spacious, right from the start, emptying great gaps of time from me, rendering my mind blank as a desert. But every time he was there, I felt a terrible oasis of panic, a looming dread.

I outlasted him by lying there with my eyes closed, waiting for the terror to pass, imagining myself playing through Bach’s first Invention, note by note, in my mind, to try to be in this moment, and that one, and the next, and the next, until I remembered my way all the way through. Once he finally left and it was safe to open my eyes, I found his message on the bedside table. A sketch of me, reading a book on a bed, in a room cluttered with books and paintings—was this our bed, our busy room?— and a note: “A few kisses, Lise. I’m sorry. M.”

In the hospital they gave me medicine that made my lungs burn as though I’d just finished singing Schubert Lieder. That faded me to an empty blankness. They asked me questions, so many questions. What day is it? What year is it? What is your name? How old are you? Who is the president? Why did you cut your wrists?

I was roused from my sleep early in the mornings, before breakfast, and pierced with needles. I kept my eyes closed while they put me on stretchers, strapped me into movable beds, wheeled me into rooms where I was injected with something that flooded me with emptiness before the shaking began. When I did open my eyes, I stared at fluorescent lights on the ceiling, waiting. I came to know what to expect from the treatment. I saw it, once. Done to someone else. I wasn’t supposed to see. But I wanted to know what had been happening to me, what filled the space between the terror rush of adrenaline and waking up in my room, in the dark. I watched through the scratched, clouded window in the door. I saw a woman restrained on a bed. She was so still, no panic, no anticipation. Perhaps it was her first time. I saw the flash of a needle in a nurse’s hand. Then it began. The woman struggled against her restraints, moaning, writhing, her eyes rolling back in her head and her body arched with the initial assault. Her body rattled with convulsions, seizures shaking her arms, legs, trunk. It seemed to go on forever, the nurses just standing by, almost impatiently waiting for the flailing to end. Finally, she stopped moving. For a still moment, it seemed as though she barely breathed. Then a nurse placed a stethoscope on her chest, listened for a moment, and glanced toward the window where I stood. I moved away from the door. Whenever I was restrained on a bed, ready for treatment, I tried to let Chopin études flood my brain. I heard them all at once, my favorites colliding, a snatch of one mashed up against a strain of another. One of them—the “Revolutionary” étude, “Tristesse,” maybe “Winter Wind”— would eventually float to the top, and I would allow myself to be filled by it. Every time, afterward, when I was awakened, I felt battered, broken, a heap of shattered bones. It took time, who knows how much time, until I could remember where I was, until my body came back to me and I felt less bruised. The music in my head became hidden, just emptiness inside me. I would drift off to sleep in the blankness, and when I woke, the space inside my head would feel infinite.

He did this to me. Mor did. That’s important for you to remember.

The day I finally decided to open my eyes and keep them open for the doctor, after hearing his voice piercing the silent spaces, I was bleary from the treatment. I felt hands on my wrists, my arms, my legs; the sensation of buckles being removed, straps undone; I heard the clank of metal as things were unfastened. I covered my eyes to block out the light, and a voice told me not to close my eyes anymore, that it was safe to look.

He was a collection of facts: square black glasses, reddish mustache and beard. Hands gripping a clipboard, a pencil, a sheaf of paper. Long white coat brilliant in the harsh light. Legs crossed in a low chair. It took a while to register in my brain as he introduced himself.

The other doctors were interchangeable, frowning, rough. They appeared from nowhere to observe each of us in turn, note things on clipboards, dictate observations to the nursing staff in code I didn’t understand but felt the intention of. Dr. Zuker was different. He was the one who promised me I could play, who swore that if I kept my eyes open, if I used my voice, if I stayed with him and answered his questions, he would let me practice again.

“When you are strong enough,” he kept saying, as if he could possibly know how to determine that.

He pestered me with questions, things I didn’t want to answer, and told me things I didn’t want to know. There was an absurdity to what he was saying that I could not reconcile with the information he was trying to impart. He told me that I’d cut my wrists. That didn’t make sense. And yet there was the proof, my aching hands and arms, bandages still covering the wounds. He told me about the various procedures the doctors wanted to perform, the word transporting me to a concert hall, visions of doctors flourishing their instruments, virtuosos wielding scalpels, a triumphant standing ovation, the surgeons bowing, gesturing grandly to my unconscious form on the operating table.

I didn’t remember hurting myself, but I remembered wanting to be dead. To be left alone, with my eyes closed, with the music. I remembered letting the nurses change my dressings, bring me food, change my hospital gown, clean me. I remembered that I didn’t care. I was music, pure music, and I would not speak, would not open my eyes, would not be bound by time.

Once, when my eyes were still closed, I’d felt the brightness of an open window to my right, heard noises from the hallway on my left, waited for the nurses to leave, and then I opened just one eye, secretly. The floor was a sea of sick-green tiles, and I was shocked by the presence of even that dull color after so many days of closed-eyed darkness. Shortly after that, I spoke for the first time in the hospital, my voice faltering like a clarinet with a split reed, as I asked for Mor and heard the nurse tell me, “Your husband? He knows where you are, don’t worry. He’s the one who signed the papers.” She surprised me with her hand on my hand, and I imagined for a moment that this was a gesture of compassion until I realized she was shaping my hand around a paper cup, cool and weighted with water. “Now stick out your tongue for the medicine, and drink up.”

At some point, after I obeyed them, after I started opening my eyes, I remember being put into a robe stiff from industrial washings, helped into a wheelchair, wheeled down a hallway punctuated by doors with no windows. There were other people in the hallway, sitting in wheelchairs like me, some staring blankly, some sleeping, some talking and gesturing to people I couldn’t see. I was pushed through a doorway into a room filled with other people in wheelchairs, old women sitting with blankets in their laps, young women sitting near windows, nurses soothing women who whispered angrily, talking to women who would not answer.

I remember seeing the piano.

It was in the corner of the common room, plants and books on its lid as if it were a side table or a bookcase. I remember it beckoning to me like a beacon, begging me toward it. Together, I knew, we could escape this deadened room with its scuffed black-and-white checkered linoleum, ratty and sagging olive-green couches, cafeteria-style tables; together we could transcend time, if I could only play it. It was near a window. I remember the sunlight streaming in, looking warm on the keys. I remember my impulse was to clear the plants and books from the top of it, put them in a more proper place: a table, a bookcase, a cabinet. A piano should not be a desk. Even a spinet deserves to have the fullness of its own sound, a lid unencumbered by objects that could go elsewhere. I remember fingering the C-sharp major scale in my lap. Pressing down against my own leg was not the same as pushing against a real key, but I imagined the hammer striking the strings, the twangy sound of the instrument, as best I could. Most likely the spinet would be tuneless, the action sluggish, the pedals too muddy. It wouldn’t matter. I planned to savor every moment of the experience.

I remember Dr. Zuker materializing at my side, telling me, “Do you see, Mrs. Goldenberg? We have a piano here. Perhaps, if you keep your eyes open, and keep talking with me, and if your husband allows, you may play it.”

I remember that word.

Allows.

__________________________________

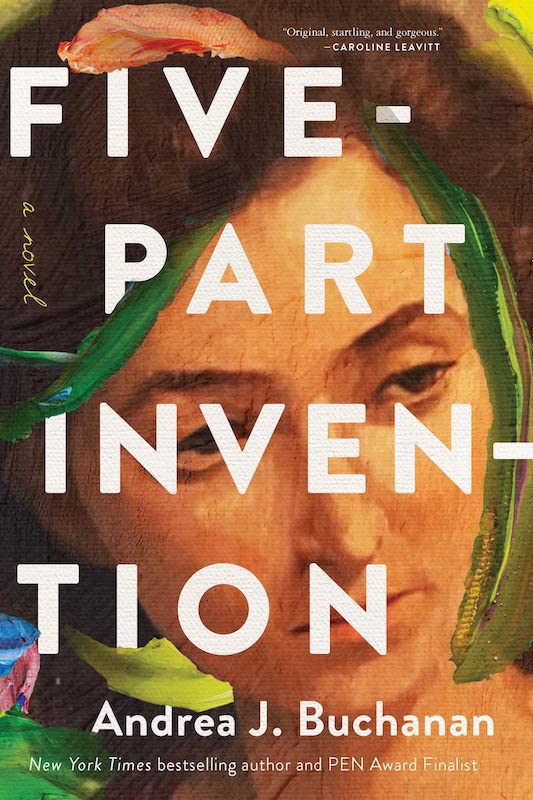

From Five-Part Invention by Andrea J. Buchanan. Used with permission of the publisher, Pegasus Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2022 by Andrea J. Buchanan.