Five Books You May Have Missed in November (That Will Make Good Gifts!)

From a Hawaiian-Chinese-Norwegian Modern-Day Ninja

to the Alaskan Fishing Village

All of us who write about books say the same thing at this time of year: “Books make the best gifts.” I wrote it myself in another piece just this week.

But the best books to give, in my opinion, are those that introduce recipients to something new: A perspective, an event, a place. Each of the books on this month’s list would fit that bill. An added bonus: Each of these titles comes from a small or university press. If you buy one at an independent bookstore? Triple play!

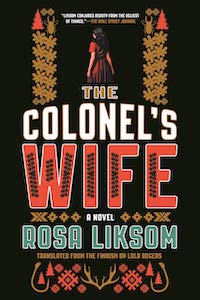

Rosa Liksom, The Colonel’s Wife (translated by Lola Rogers)

Graywolf

The Colonel’s Wife introduces readers to a woman forgotten by time. Married to a member of the Nazi-sympathizing Finnish Whites, this “Wife” witnessed Third Reich horrors—and more than a few connubial ones. Liksom (Compartment No. 6) sets her short, powerful novel in Finland’s heavily wooded far north, a place with which she’s familiar, having been raised in a Sami village of just eight families. Perhaps only someone with that quiet and beauty and desolation in her bones could understand how it could help such an unlikable narrator unspool a story of paradox: Love and hate, grandeur and simplicity, passion and pettiness. Perhaps only someone who is also a visual artist (like Liksom) could find a way to let the story unspool without sentimentality or sensationalism. One of the gifts that middle-aged authors like Liksom provide is to act as a bridge between the 20th and 21st centuries, having known characters like this protagonist—but also not having borne this protagonist’s burdens.

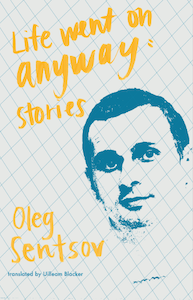

Oleg Sentsov, Life Went on Anyway: Stories (translated by Dr. Uilleam Blacker)

Deep Vellum Press

Here in these United States, literature takes a back seat to, well, almost everything. But in some places, creating and publishing books remains an act of political dissent. Life Went on Anyway: Stories is a debut collection from the Ukrainian film director, writer, and dissident whose current incarceration may come from opposing Russia’s invasion and occupation of his country’s eastern region, where he lived in Crimea. His kidnapping, probable torture, and unfair trial have been documented by organizations around the globe, including PEN Internationals, Amnesty International, and the European Film Academy. The European Parliament awarded him the 2018 Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought after he went on a 145-day hunger strike to urge Russian authorities to release all unfairly imprisoned Ukrainians in Russia. His final words at his trial were “Why bring up a new generation of slaves?” Will the publication of this book contribute to his release from prison camp? We can only hope, and meanwhile know that Sentsov’s sensitive, humorous accounts of life during a kind of wartime can remind us of the power of words.

Tori Eldridge, The Ninja Daughter

Agora Books

The Ninja Daughter comes with this bio: “Tori is a Hawaiian-Chinese-Norwegian modern-day ninja who was born and raised in Hawaii. She holds a fifth-degree black belt in To Shin Do Ninjutsu and has traveled the USA teaching seminars on the ninja arts, weapons, and women’s self-protection.” Who could resist, especially when it’s described as “Kill Bill meets The Joy Luck Club?” Lily Wong is a Chinese-Norwegian “modern-day ninja” who fights the Los Angeles Ukrainian mob, sex traffickers, and even her own family to save two desperate women and a child. It’s not Serious Littrachoor, but it is serious fun, and I defy anyone who picks up this pace-y feminist thriller to put it down before finishing.

Mia Heavener,Under Nushagak Bluff

(Boreal Books/Red Hen Press)

Perhaps this writer is feeling the cold and dark, since Under Nushagak Bluff is the second novel on this list in a remote, frigid location. Here, the setting is 1930s Alaska, in the Yup’ik fishing village of Nushagak, where Marulia and her daughter Anne Girl must cope with a damaged skiff. The owner of the boat that did the damage is Norwegian John Nelson—every year men from Scandinavia, Japan, the Philippines, and other places come to fish the waters of Bristol Bay. When Anne Girl begins an affair with John, her mother disapproves. However, the lovers marry and have a girl of their own, Ellen. Through this lens, Heavener examines two different cultures, gender roles, the idea of statehood, and fishing skills, always hewing to the distaff, indigenous side of things which may be why, when the action progresses to the 1940s, that World War II is never mentioned. That doesn’t really matter, because readers will by then be so caught up in the careful balance of life in Nushagak that nothing else seems to matter.

Masatsugu Ono, Lion Cross Point (translated by Angus Turvill)

Two Lines Press

Lion Cross Point follows ten-year-old Takeru during a summer that follows terrible memories. Alone, he befriends his new caretaker and a neighbor, while retracing his mother’s history in their home village. Ono, who won Japan’s Akutagawa Prize for emerging writers, employs a ghost named Bunji as a device to help Takeru process his trauma, something that has certainly been seen before, but not necessarily with this author’s delicate touch. Bunji, named for and resembling a boy who disappeared years before, does not hector or manipulate Takeru. His appearance and memory allow Takeru a space. Gorgeous without flourish, Lion Cross Point should be required reading for anyone who has experienced grief, especially the kind that hits closest to home.

Bethanne Patrick

Bethanne Patrick is a literary journalist and Literary Hub contributing editor.