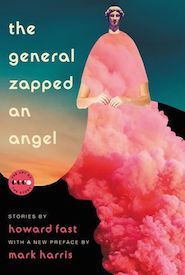

The Unapologetic Politics

of Howard Fast

Mark Harris on the Writer Who Stood Up to Joseph McCarthy

In 1950, Joseph McCarthy tried to silence Howard Fast. It was a fool’s errand. Called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Fast refused to name names, served three months in prison for contempt of Congress, and had to resort for some time to a pseudonym to survive the blacklist. It was scarcely a speed bump in a career of astonishing variety and prolificity.

Fast was a novelist, an essayist, a poet, a playwright, a young adult author before that was even a named genre (his April Morning was a staple of middle school curricula for decades), a biographer, an autobiographer, and, as this volume attests, a short story writer. Something like 100 books bore his name (or one of his aliases). His first novel was published in 1933, when he was 18, and his pace barely abated for the next 70 years. Even in prison, Fast didn’t take a break; he started what would become one of his most famous novels, Spartacus, self-publishing it to great success upon his release. He wrote—including, during the blacklist years, for the Daily Worker—like it was a job and a calling. And he wore his politics on his sleeve.

By the time this delightful, imaginative, irate collection was published in 1970, those politics had evolved, but not mellowed. Fast was no longer a Communist, having become disillusioned with Stalin in the early 1950s, but his rage at American militarism, greed, and profiteering did not abate, and it resounds through these nine stories like a hand pounded on a breakfast table over strong black coffee and the morning paper. This collection offers a mix of sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and dystopian black comedy, a combination of moods that emerged from a political moment when US involvement in the Vietnam War was the subject of daily household argument, and from a cultural moment when Star Trek had recently merged speculative fiction with liberal social consciousness and brought the results into American homes.

Fast leapt genres, tones, and styles to suit his interests. In the title story, an American general in Vietnam who began his assaultive career by killing puppies works his way up to shooting an actual angel out of the sky; it’s a savage portrayal of military swagger and heedlessness, the prose equivalent of a satirical protest song. “Tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal” features a guest appearance by the devil, who—Fast would have it no other way—naturally self-identifies as a conservative. In “The Mouse,” visitors from another planet land their small flying saucer in a suburban yard, imbue a mouse with the consciousness of a human, and leave him in suicidal despair, the only rational response to a world that, for the first time, he now understands.

The stories in The General Zapped an Angel are not subtle, fussed-over pieces of prose. Straightforward and blunt, most of them read like a good day’s (or a good few days’) work, written in plain English to get the point across. Fast did not suffer from writer’s block or a lack of ideas. His 2003 New York Times obituary quotes him as saying, “The only thing that infuriates me is that I have more unwritten stories in me than I can conceivably write in a lifetime.” It didn’t take much to get him started—these pieces are, for the most part, a whim or a wince or a grin or a grimace at the state of the world spun into brisk narrative. But cumulatively, they offer readers a powerful, plaintive kind of undertow: they have the feel of religious parables, recognizably Jewish in their rhythm and their stretchiness, their shrugging joke structure and their moral rigor, their humor and their outrage. Their sense of futility feels bone-deep, the product of a life’s contemplation of mankind racing toward the edge of a cliff.

Because many of these stories are the product of their historical moment, it’s jolting to see that their subject matter is anything but quaint. One can’t exactly laugh off “The Wound,” in which nuclear weapons are reimagined as the latest (and last) tool of oilmen looking for a new way to dislodge deposits beneath the earth’s surface—it’s a heart’s cry that is no less resonant today than it was half a century ago. (Does anyone doubt what Fast would have to say about fracking?)

And in at least one case, Fast appears to have had the assistance of a time machine. “The Vision of Milty Boil” tells the story of a powerful New York City real estate tycoon—a man obsessed with amassing power and wealth who, despite being derided as an idiot by the skeptics around him, proceeds to remake the cityscape in ways systematically designed to make himself larger and everybody else smaller. In this mordantly funny little masterpiece, bedrooms, buildings, even humanity itself can all be tailored to soothe the insecurity and enhance the vanity of a man who absolutely does not want to be seen as small. Fast follows Milty into the 1980s, the 1990s, and beyond, finally crafting an epitaph that is perfect for him and just as apt for us. Like many of the stories in The General Zapped an Angel, it’s a nightmare that eventually releases us back into our own reality with the snap of a bitter little joke. And there is particular pleasure in unearthing it 50 years after it last occupied Fast’s mind.

To read these stories is to open a time capsule prepared by a man who could not have imagined what the world would become and yet, as often as not, managed to take a pretty impressive guess.

__________________________________

From The General Zapped an Angel by Howard Fast. Used with the permission of Ecco.