Five Books Making News This Week: Space, C.D. Wright, and Fake Steve Jobs

Janna Levin, Nathalia Holt, Maggie Nelson, and More

As the news of Prince’s death expands into an international purple-lit memorial marathon, music journalist Alan Light, author of Let’s Go Crazy, takes to the air to talk about Prince’s life, his artistic genius. and his passion for creative freedom. (Read about the shooting of Purple Rain here.) Cultural critic Maggie Nelson, whose book The Argonauts won the National Book Critics Circle award for criticism in March, returns to a family tragedy that shaped her life. An astrophysicist and novelist documents cutting-wave work on black holes; a microbiologist writes about NASA’s team of women; Fake Steve Jobs takes a job at a Boston firm, leaves, and writes about it. Two posthumous books by the late C.D. Wright are released.

Maggie Nelson, The Red Parts

Nelson’s aunt was murdered at age 23, in 1969. She first wrote about it in the poem cycle Jane and later in The Red Parts, the autobiographical work drawn from attending the trial of the man accused 36 years after the crime. The Red Parts, first published in 2007, was reissued this month. (New Yorker critic Hilton Als calls it “devastating” in his profile of Nelson and her “many selves.”)

“Nelson’s resistance to the easy answer, her willingness to reach a kind of conclusion and then to break it, to probe further and further, to ask about her own complex and not entirely noble intentions instead of facilely condemning others, make The Red Parts an uneasy masterpiece,” concludes Annalisa Quinn (NPR). “It is a sounding, a wondering, not an autopsy (It was murder, I say!) or a condemnation. Nelson allows space for the truth: Maybe grief is a repeating cycle, not a hurdle to be passed, maybe there is no immunization, maybe we’ll never feel entirely safe. Maybe women will always have to negotiate between freedom and safety, on and on in endless compromise.

Eve Conant (New York Times Book Review) writes:

Maggie Nelson’s memoir of her aunt Jane’s killing, which was one in a series that was labeled “the Michigan Murders,” opens with a quotation from Nietzsche: “In all desire to know there is already a drop of cruelty.” These words take us directly into Nelson’s conflicted psyche. A 34-year-old poet, she never met Jane, yet became so obsessed with her death she fell prey to what she calls “murder mind.” By day she researches rhyming words for “skull” and “bullet.” By night she is assailed by sickening images with “the slapping, prehensile force of the return of the repressed.” But she is ripped from her grim reveries when an investigator announces that — thanks to a DNA match — Jane’s unsolved case has been reopened and that an arrest…is imminent.

Alexandra Molotkow (New York) notes that in Jane and The Red Parts, Nelson “catalogs the scripts to which female victims are assimilated — thrillers and torture porn, but also the true-crime books, ‘serial-killer chic’ Web sites, and newspaper articles that diminish the person while savoring her pain, pairing a ‘she had so much to live for’ sentimentality with quasi-pornographic descriptions of the violence each girl had suffered.”….” Nelson never claims that works are harmless, Molotkow adds, “but she doesn’t condemn. Instead, she documents her responses, faithfully reproducing her own impressions and convictions, which are often very strong, and often at odds. She diagrams her knots. ‘True moral complexity is rarely found in simple reversals,’ she writes. ‘More often it is found by wading into the swamp, getting intimate with discomfort, and developing an appetite for nuance.’ Nelson never flattens or contorts her own insights — she is not a polemicist; ambivalence is her element.”

And here is Lyz Lenz (The Rumpus): “Although it can be classified as true crime, The Red Parts has none of the trappings of a whodunit. It doesn’t look for answers, it just looks unflinchingly at the wreckage, the loss, the love and the fear. It bears witness.”

Janna Levin, Black Hole Blues

Levin, an astrophysicist and novelist, tracks the decades leading up to September 2015, when the measurement of gravitational waves created by black holes colliding at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) confirmed Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Her book ranks high with critics.

Maria Popova (New York Times Book Review ) explains the genesis of the “magnificent machine” Levin chronicles—an apparatus that would detect “the sonic message of the cosmos as it made contact with us via gravitational waves — ripples in the fabric of space-time, first envisioned by Einstein in his pioneering 1915 paper on general relativity.”

“After half a millennium of exploring the cosmos through light, we have entered a new era of sonic exploration,” she concludes. “But as redemptive as the story of the countless trials and unlikely triumph may be, what makes the book most rewarding is Levin’s exquisite prose, which bears the mark of a first-rate writer: an acute critical mind haloed with a generosity of spirit.

Levin’s “easy style,” writes John Gribbon (Wall Street Journal) “makes readers feel as if they are sitting in on her interviews or watching over her shoulder as she describes two black holes colliding—‘an event more powerful than any since the origin of the universe, outputting more than a trillion times the power of a billion Suns.’” Gribbon has a couple of quibbles (he is uncomfortable with her “too detailed” portrayal of “rivalries that led Mr. Drever to be pushed out of the project at the end of the 1990s”), but he concludes, “This is a splendid book that I recommend to anyone with an interest in how science works and in the power of human imagination and ability.”

Nathalia Holt, The Rise of the Rocket Girls

Microbiologist Holt tracks the teams of mathematically gifted women who worked at NASA from World War II to the launch of Sputnik and the decades after. Hers is a rare look at a little-known team.

“Before PCs or smartphones or even clunky mainframe IBMs, a little-known group of women known as ‘computers’ were using paper and pencil to calculate thrust, velocity, and trajectories for the first American rockets,” writes Julia M. Klein (Boston Globe).

“While dreaming of space rather than war, they were indispensable to the construction of the first ballistic missiles in the 1940s and ultimately helped design spacecraft that would explore the moon and the rest of the cosmos.” She gives Holt credit for bringing their story—their “intimate accounts of their accomplishments, family lives, and the sometimes unsettling mix of opportunity and discrimination they encountered”—to light.

“Even as not-so-human computers made by IBM join their offices, diligent, talented women such as Barbara Paulson, Helen Chow and Margie Behrens continue to use their heads and pencils to help America respond to Russia’s October, 1957, launch of Sputnik with the successful launch four months later of Explorer I,” writes Gene Seymour (USA Today). “Throughout the succeeding decades, when they work on satellites and robots that map the moon, register temperatures on Venus and photograph the surface of Mars, these women are vividly depicted at work, at play, in and out of love, raising children — and making history.”

Dan Lyons, Disrupted

At 52, the author of the satirical blog The Secret Life of Steve Jobs goes to work for HubSpot, a Boston marketing software firm. He lasts twenty months. He writes about it. Some critics find him funny. HubSpot’s co-founders do not. They post a response on LinkedIn that includes FAQs like this: “1: When people were fired did you actually call it a graduation? Unfortunately, yes.”

Dwight Garner (New York Times) has fun with Disrupted:

You are not the kind of guy – not at your age, and not with your résumé — who should be working at a place like this.

But here you are. It’s your first day at HubSpot, a Boston start-up company, plump with $100 million in venture capital. You’ve been hired as a marketing fellow, whatever that means. You’ve been granted a small tranche of stock options.

This is 2013. You walk into HubSpot’s vast, open office space, gaze at the hundreds of dewy employees, and think: It’s like a Montessori frat house in here. There are foosball tables and video game consoles and beanbag chairs and Nerf guns. Dogs roam the hallways. Is that a wall of free candy? …You note, distressingly, that you are “literally twice the age of these people, in some cases more than twice their age.”

Led to your desk, you find that you are expected to sit on a big rubber ball on a rolling frame. (The ball is orange, of course.) You fear you will fall over and break your pelvis. You ask for an actual chair, with four legs. You begin to feel very, very old.

Nancy Franklin (New York Times Book Review) calls HubSpot “tailor-made” for someone like Dan to write about. “HubSpot embodies everything that’s ridiculous about the culture of start-ups, and in the bargain it reinforces every paranoid worry Lyons has about his age.”

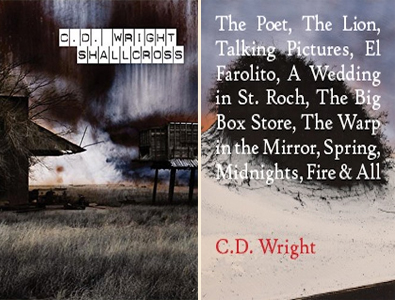

C.D. Wright, Shallcross and The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farlolito, A Wedding in St. Roch, The Big Box Store, The Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All

C.D. Wright, winner of the National Book Critics Circle award for her 2011 collection One with Others, died in January only days after her collection of essays about poetry The Poet, the Lion, Talking Pictures, El Farlolito, A Wedding in St. Roch, The Big Box Store, The Warp in the Mirror, Spring, Midnights, Fire & All was published. Shallcross is her first (but not her last) posthumous work. Both are greeted with reverance.

This “extraordinary collection of poems should not be read as any kind of a final statement but instead as the next installment in a series of books by a poet at the height of her powers,” writes Craig Teicher (Los Angeles Times), who notes that “she had submitted her next manuscript to her publisher already.” Of “Breathtaken,” the book’s centerpiece, he writes:

The 20-page poem is a relentless stack of fragmentary descriptions of murders lifted from “the NOLA.com Crime Blog … with contributions from an extended cast of reporters for the Times-Picayune.” The descriptions begin midway, bleed together, add up to a disturbingly incoherent yet somehow unified whole: New Year’s Day / in front of his grandmother’s house, 6th Ward / shot 14 times … / at a graduation party in the backyard / a girl totally in love with poetry/ mother of a 30-month-old … the father ambushed in his car/ a few days after she learned he was pregnant. Who are these people? Wright gives them their humanity without their names, as if to remind us that even statistics have mothers, lovers, children. She transforms journalism into poetry, leaving us with feelings rather than thoughts, with a sense of culpability and responsibility that, as observers of injustice, we share.

“She transforms journalism into poetry,” he adds, “leaving us with feelings rather than thoughts, with a sense of culpability and responsibility that, as observers of injustice, we share. That’s Wright’s most remarkable power, to make her readers feel both culpable and capable. Compassion, which her poems engender almost instantly in anyone who pays attention, can become a form of action, even activism in her work.”

“We think of criticism as something utilitarian, probably dry,” writes Daisy Fried (New York Times Book Review) of Wright’s January 2016 collection. “But this collection of prose fragments about poems, poets, poetics and politics reads like a journal of explorations and commitments. The fragments, as short as two lines and as long as nine pages, are culled from essays and lectures: outtakes remixed to appear at surprising angles. They are always smart, sometimes elliptical, frequently strange.” And, she concludes, “Things here fit together even as they fragment. This book is partially a portrait of America.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.