Five Books Making News This Week: Monsters, Memoirs, and Mountains

Jeff VanderMeer, Patricia Lockwood, Daniel J. Sharfstein, and More

Bret Anthony Johnson’s “Half of What Atlee Rouse Knows About Horses” wins the Sunday Times Short Story Award, the richest story award in the world (it comes with £30,000, or $38,000+). In the story, judge Mark Lawson notes, “a small patch of Texas cattle country opens up long vistas on love, death, memory and the survival instinct, human and equine . . . Small details from American and animal lives take on vast significance, and every line has the kick of a horse.” Read the story here. The Edgars go to Noah Hawley’s Before the Fall, Flynn Berry’s Under the Harrow, and Ruth Franklin’s Shirley Jackson biography, among others. The Philip K. Dick Award for distinguished science fiction published in paperback original goes to Claudia Casper’s The Mercy Journals. And Congrats to Granta Best Young American Novelists: Jesse Ball, Halle Butler, Emma Cline, Joshua Cohen, Mark Doten, Jen George, Rachel B. Glaser, Lauren Groff, Yaa Gyasi, Garth Risk Hallberg, Greg Jackson, Sana Krasikov, Catherine Lacey, Ben Lerner, Karan Mahajan, Anthony Marra, Dinaw Mengestu, Ottessa Moshfegh, Chinelo Okparanta, Esmé Weijun Wang and Claire Vaye Watkins. The new Granta issue featuring their work here.

Pulitzer Prize winner Elizabeth Strout continues to draw raves for her small-town characters, Poet/Twitter phenom Patricia Lockwood tears it up with her memoir, The Southern Reach’s Jeff VanderMeer goes post-apocalyptic, Daniel Sharfstein has an eloquent and timely take on the Nez Perce wars, and Kristin Radtke “pulls no punches” in her new graphic memoir.

Elizabeth Strout, Anything Is Possible

The Pullitzer Prize winner (for Olive Kitteridge) is back with interlinked stories connected to her latest, I Am Lucy Barton. She’s a genius at creating small-town characters. “I use myself—I’m the only thing I can use—but I’m not an autobiographical writer,” Strout tells The New Yorker’s Ariel Levy. “Some people have an idea,” she continued. “I just see a person, and I start describing who this person is.”

“Like Olive Kitteridge, Anything Is Possible is really a necklace of short stories about people in a small town, studded with clues about who’s connected to whom,” notes Jennifer Senior (New York Times). “(Strout was born to be an omniscient narrator, born to flit and swoop from one crooked perch to the next.)” She adds: “You read Strout, really, for the same reason you listen to a requiem: to experience the beauty in sadness.”

“Elizabeth Strout’s new book grows more impressive with each passing page, as it becomes clear that [she] is slowly, subtly building one big story from a bunch of small ones,” writes Kevin Canfield (Kansas City Star). “There are nine chapters in Anything is Possible. Each can be enjoyed as a stand-alone short story. But read them in order, and you’ll see that they fit together like tiles in a mosaic. Collectively, they form a moving work of fiction about the pain we inflict on those close to us, and the heroic acts of kindness that make life bearable.”

Ed Tarkington (Knoxville News-Sentinel) writes:

This rich, luminous volume makes clear why Elizabeth Strout has become one of the most celebrated and beloved literary voices of her generation. For stories that so nimbly and gracefully peel back the layers of human identity and self-consciousness, the most useful comparison is the old masters. Like Joyce, Strout gives Homeric scope to the lives of outwardly unremarkable people. And she is somehow able to plumb such depths in prose that is lyrical and incisive but as unadorned and direct as her characters. Her sentences feel effortlessly fluent, the insights both brilliant and natural, bearing the weight of universal truth. Not a single word is misplaced in this extraordinary book, the title of which is apt, for Elizabeth Strout has proved again that, indeed, anything is possible for a writer of such seemingly limitless gifts.

Jackie Thomas-Kennedy (The Millions) finds much to love: “Strout’s genius is her ability to wring deeply moving stories from such ungenerous sources; to reveal, through hurried gestures and single syllables, the welter of feeling the Lydias and Olives of the world are trying to conceal. When Strout gives us the same images again and again, in one story after the next—‘fields of green soybeans,’ for instance—she’s shifting our attention to the familiar and the bearable, to the things her characters would prefer to talk about. In the best of these stories, such reticence is balanced by outburst—whether silent realization or, better yet, actual confrontation.”

Alexis Burling (San Francisco Chronicle) concludes:

In its entirety, Anything Is Possible is both sweeping in scope and incredibly introspective. That delicate balance is what makes its content so sharp and compulsively readable. In fact, one might say that this—Strout’s winning formula—has succeeded once again. With assuredness, compassion and utmost grace, her words and characters remind us that in life anything is actually possible. The highs. The lows. And everything in between.

Patricia Lockwood, Priestdaddy

Poet and Twitter star Lockwood makes the shift to memoir with her distinctive sardonic voice intact. She and her siblings developed their fierce sense of humor “as a sort of armor, a front line of defense against what was basically an unreasonable atmosphere,” she tells the Los Angeles Times’s Kate Tuttle. Her father “sucked up all the oxygen—he was a big screamer too, and very impulsive.” The Publishers Weekly starred review puts it like this: “Mary McCarthy’s Memories of a Catholic Girlhood meets David Sedaris’s Me Talk Pretty One Day, with a poetic twist.”

Christian Lorentzen (New York) calls Lockwood’s new memoir “part origin story, part narrative of her time in the wilderness. Except here the wilderness is actually a homecoming, a regression from low-rent provincial American hipster paradise back to the crucifix-appointed parental home—in fact a rectory, because through a loophole in Catholic doctrine Lockwood’s father Greg is that rare animal, a priest with a wife and five children—in the un-bohemian heartland.” He adds, “It’s mostly the story of a very loving and eccentric family, full of American contradictions and dense with brilliant sentences that Lockwood seems to toss off as if she were brushing lint from her sweater.”

Paul Laity (The Guardian) writes:

Patricia Lockwood’s dazzling comic memoir is set in midwest America and centers on a man who likes to clean his gun, listen to Rush Limbaugh and drink from a mug that reads “I love my ‘white-collar’ job” . . . Upstairs in the family home, he shreds his electric guitar in a prog-rock frenzy and sips cream liqueurs (“He looked like a gigantic brownie drinking drops of dew”). He has a habit of yelling out “Hoooo-eee” for no particular reason, cooks a great deal of meat and dresses either in his full priestly regalia or nothing but his underwear (“He was wearing his most formal boxer shorts, the ones you could almost not see through”).

James Parker (The Atlantic) concludes:

Poetry heals and integrates; online, things fly apart. God knows what kind of feedback Lockwood gets, the trolls and mugwumps and flickering testicular wraiths she has to contend with. I can see her in my mind, post-religion, post-family, a savvy, wounded poet hanging over an electronic abyss. But the pen that can describe a rural motel room as looking “like the place where Smokey the Bear went to cheat on his wife” is sharp enough for the occasion, for the moment. Can poetry address the massive and systematic degradation of the mental environment? Lockwood, her personae shimmering, her linguistic sensors tingling, is one of the few poets tough enough and shrewd enough to try.

Jeff VanderMeer, Borne

The author of the Southern Reach trilogy goes post-apocalyptic.

“VanderMeer couldn’t care less about technological plausibility, and Borne isn’t, at heart, science fiction,” writes Laura Miller (The New Yorker). “With the toppling of the old forms of order, Rachel, Wick, and the other residents of the city have been plunged into a primordial realm of myth, fable, and fairy tale. Their world is a version of the lost and longed-for territory of fantasy and romance, genres that hark back to an elemental, folkloric past roamed by monsters and infested with ghastly wonders. Mord’s rival is a mysterious figure called the Magician, a woman clad in biotech robes that enable her to appear and vanish before Rachel’s eyes. The Magician’s minions are genetically altered children whose ‘iridescent carapaces’ and ‘gossamer wings’ recall Titania’s fairy attendants. In accord with Arthur C. Clarke’s famous dictum, the technology devised by the Company has become indistinguishable from magic, but this is not so much a midsummer night’s dream as it is a year-round nightmare.”

Charley Locke (Wired) writes:

Part sci-fi, part family drama, Borne envisions a world shaped by both technology and the supernatural. It’s a story of domesticity and tension under absurdist circumstances, as its three protagonists form an unlikely bond while being tyrannized by a massive flying bear and gangs of feral, genetically modified children. The book…is a significant departure from the author’s previous work. But fans worried that its human-devouring namesake and far-future setting mean it’s lightyears away from his beloved Southern Reach trilogy should fear not. Beyond its post-apocalyptic people-eaters, Borne maintains a wry self-awareness that’s rare in dystopias, making it the most necessary VanderMeer book yet.

“Jeff Vandermeer’s lyrical and harrowing new novel, may be the most beautifully written, and believable, post-apocalyptic tale in recent memory,” writes Elizabeth Hand (Los Angeles Times). “A considerable achievement, considering Borne features not just a near-future, nameless city; an enormous, sentient, cataclysmically destructive bioengineered bear; and the endearing intelligent cephalopod who gives the book its title.”

Daniel J. Sharfstein, Thunder in the Mountains

Sharfstein, who teaches law at Vanderbilt and has been awarded fellowships for his research on the legal history of race in the United States, looks back at the monumental act of treachery by the U.S. government that triggered the Nez Perce Wars. “I think that was a crucial period in our history because it was the time when the battles that we’re still fighting were set . . . battles over the contours of liberty and equality over the relationship between race and citizenship and really over the proper size, scope and role of government,” Sharfstein tells NPR’s Ray Suarez. “And in Joseph’s story, I think we see the nature and power and necessity of protest and moral witness.”

Julia M. Klein (Chicago Tribune) writes, “In luminescent prose, Sharfstein recounts the ordeals of this nomadic tribe of hunters and fishermen whose cherished homeland was the Wallowa Valley of Oregon and whose champion was the legendary Chief Joseph.”

Nick Romeo (Christian Science Monitor) calls Sharfstein’s second book a “magnificent and tragic new history of the conflict,” He concludes:

However vivid the material and well-structured the narrative, the story is inescapably tragic and often painful to read. It’s a powerful reminder that Americans live on lands stolen by force and without provocation. It’s also a tantalizing glimpse of a possible future that never materialized. While the American government essentially presented Native Americans with a choice between assimilation and annihilation in the 19th century, Joseph imagined a third alternative—equal treatment and legal standing for tribes that chose to pursue a traditional lifestyle. But as Joseph and his tribe learned through years of mistreatment by agents of the US government, equal protection under the law was just an American myth.

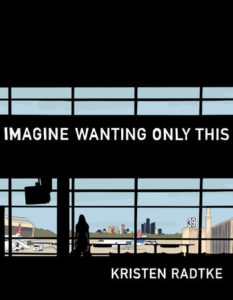

Kristen Radtke, Imagine Wanting Only This

Radtke’s first book, a graphic memoir, received three starred reviews in advance of publication, and she was featured as one of three Los Angeles Times Faces to Watch in January. As her book gathers steam, Radtke shows how she does it for Nylon.

Cristina Arreola (Bustle) sets it up:

In college, Kristen Radtke lost her beloved uncle to a rare, little understood genetic heart defect that doctors suspect might also be encoded in her own DNA. (“It’s like mush,” she writes in her memoir. “The heart beats itself to mush.”) In the aftermath of his death, Radtke developed an obsession with ruins that propelled her through early adulthood and helped her come to terms with life’s most bittersweet truth: everything—and everyone, including her—is temporary. In her Imagine Wanting Only This, Radtke tells the story of her grief and search for meaning through a juxtaposition of grayscale drawings and concise, propulsive prose.”

In her graphic memoir, writes Jim Higgins (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel), “Green Bay native Radtke grapples with loss, collapse and impermanence . . . She’s both a strong writer and an adept, fluid artist. She has a word lover’s eye for found text on jars, postcards, documents, websites, hand-lettering them into her art.”

Newsweek’s Chelsea Hassler calls the book “the most beautiful graphic novel you’ll read all year” and “an absolutely stunning look at what it is to recover from grief.”

Beth Kephart (Chicago Tribune) concludes:

Did you really just do that, Kristen Radtke? I said the words out loud, the first time I finished reading Imagine Wanting Only This. Are you allowed? To disarm us, to charm us, to goad us, to frighten us, to end this book the way you do?

But I have just read this book again, and indeed Radtke pulls no punches; her work is as wonderful and heartbreaking the second time through. I’m still scooped out, but I’m still deeply grateful for the towering power of Radtke’s vision.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.