Five Books Making News This Week: Longlists, Anthologies, and the Underground Railroad

Deborah Levy, Jesmyn Ward, Colson Whitehead, and More

Roxane Gay receives the Paul Engle Prize, which seems tailor-made, if you read the qualifications. “Roxane Gay,” the judges say, “has emerged as one of the strongest voices in American letters in her various roles as a writer, professor, editor and commentator.” “I write because I love it, plain and simple,” Gay responds. The San Francisco Foundation announces awards for manuscripts in progress to six Bay Area emerging writers, including Mauro Javier Cardenas, whose novel, The Revolutionaries Try Again, is due out in September; land conservationist and storyteller Obi Kaufmann, and poet/playwright Lisa Marie Rollins. Colson Whitehead’s new novel launches like a rocket, Terry McDonnell recounts his adventures with legendary writers including Hunter S. Thompson, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton, Jesmyn Ward’s anthology updates Baldwin, Deborah Levy’s new novel puts her back on the Man Booker list, and Krys Lee’s first novel is already in the running for a Center for Fiction award.

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

His fifth novel, the book Whitehead said “really scared” him, launches like a rocket. The Underground Railroad is published early (August 2 instead of September), with 200,000 copies shipped secretly to booksellers after Oprah selects it for her Book Club. The New York Times Magazine publishes a 16,000-word excerpt in special standalone print-only section. Reviewers are enthralled with Whitehead’s original take on slavery in America as envisioned with real trains carrying fugitives to freedom.

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) calls The Underground Railroad “a potent, almost hallucinatory novel that leaves the reader with a devastating understanding of the terrible human costs of slavery. It possesses the chilling, matter-of-fact power of the slave narratives collected by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s, with echoes of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and with brush strokes borrowed from Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka and Jonathan Swift.”

“This is grim material to be sure,” writes Ron Charles (Washington Post), “but hope animates the story, and Whitehead’s narrative is a fascinating lamination of disparate tones. Sentences seem to twist phrase by phrase — mocking, mourning, satirizing, celebrating. While describing the horror of the plantation, he also honors the slaves’ courage and relishes their wry humor. Elegant lawn parties are undercut by casual references to torture. But the ultimate effect of sabotaging our glossy history is to remind us that we stand upon ‘stolen bodies working stolen land.’” And, he concludes, “The canon of essential novels about America’s peculiar institution just grew by one.”

Juan Gabriel Vasquez (New York Times) compares the novel to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, noting “It doesn’t merely tell us about what happened; it also tells us what might have happened. Whitehead’s imagination, unconstrained by stubborn facts, takes the novel to new places in the narrative of slavery, or rather to places where it actually has something new to say. If the role of the novel, as Milan Kundera argues in a beautiful essay, is to say what only the novel can say, The Underground Railroad achieves the task by small shifts in perspective: It moves a couple of feet to one side, and suddenly there are strange skyscrapers on the ground of the American South and a railroad running under it, and the novel is taking us somewhere we have never been before.”

Terry McDonnell, An Accidental Life

McDonnell, a co-founder of Lit Hub, has been high up on the masthead at Outside, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated. His memoir—told in brief takes, complete with word lengths—describes his adventures editing dozens of writers, from George Plimpton, James Salter, Tom McGuane, and Richard Price to Edward Abbey and Hunter S. Thompson. Critics praise this inside look at a golden age of journalism.

Alexander Nazaryan (Newsweek) writes, “Terry McDonell is almost certainly the only editor in the history of American magazines to have played golf with Hunter S. Thompson while tripping on acid, edited the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue and had one of his ideas called ‘really stupid’ by Steve Jobs—all in a career that also involved friendships and collaborations with some of the foremost cultural figures of postwar America, from novelist Richard Ford to actress Margot Kidder. As an editor who worked at seemingly every great magazine in print other than Cat Fancy, he mainly wants to run his fingers along the fine grains of the editing life, which might involve tracking down Edward Abbey in a rural Utah bar or fielding a complaint from Spike Lee about an Esquire headline.”

“The Accidental Life is intelligent, entertaining and chivalrous,” concludes Dwight Garner (New York Times). “It’s a savvy fax from a dean of the old school.”

Jim Kelly (Wall Street Journal) calls the writing in McDonnell’s memoir “direct and crisp, with a touch of tartness; there is not a bloated or sappy passage in the book.” McDonell, he adds, “can be sentimental, especially about friends now dead (and there are enough to fill a cemetery), but he is never mawkish. The way he describes the writing of his great friend James Salter, who died in 2015, captures why it is so pleasurable to spend time with this book: ‘You read to see what would happen, sure, but you read every word to savor the meaning and balance of each sentence—it was a way to look at life as it passed.’”

Jesmyn Ward, editor, The Fire This Time

“I read the passage where James Baldwin alludes to the fire that will come when America again is denying its past with history and with racial inequality, and saying that the result will be a fire next time,” Ward told NPR’s Audie Cornish, discussing the inspiration for the new anthology she’s curated. “And I thought, man, this really feels like a moment where we’re burning.” The 18 contributors include Claudia Rankine, Isabel Wilkerson, Edwidge Danticat, Jericho Brown, Natasha Trethewey and Kevin Young.

“Following in Baldwin’s footsteps seems a daunting task — particularly when Michael Brown or Freddie Gray have nearly as much name recognition as Beyoncé or Barack Obama,” writes Joseph P. Williams (Minneapolis Star-Tribune). “Still, Ward’s team delivers the goods, in three sections commenting on the past, current and future states of African-Americans. Their general conclusion: The nation that black people helped build, largely for free, is still conflicted at best about our presence. And being African-American can be a profound joy or a death sentence, depending on circumstance.”

Hope Wabuke (The Root) calls the anthology “a profound, necessary work of depth and insight.”

“The perils of walking, driving — indeed living — while black have become tragically apparent in recent months,” writes Charisse Jones (USA Today). “At a time of such tension,…a collection of essays chronicling the outrage, hurt and fear felt by so many African-Americans, might seem too much to bear. But ultimately, the prose and poetry contained in this concise volume…is illuminating and even cathartic.”

Deborah Levy, Hot Milk

Hot Milk is longlisted for the Man Booker (Levy’s novel Swimming Home was shortlisted in 2012). Critics find much to admire. And a few flaws.

Levy’s title, notes Sarah Lyall (New York Times), “evokes the charged connection between mother and child and also sounds a bit like ‘hot mess,’ which many of its characters are. At its heart, the book is a tale of how Sofia uses strength of will, rigorous self-examination and her anthropological skills to understand and begin to repair things that are holding her back. She learns to stand up for herself, to take risks, even to behave badly. She becomes bolder….What makes the book so good is Ms. Levy’s great imagination, the poetry of her language, her way of finding the wonder in the everyday, of saying a lot with a little, of moving gracefully among pathos, danger and humor and of providing a character as interesting and surprising as Sofia.”

“Levy has spun a web of violent beauty and poetical ennui,” concludes Leah Hager Cohen (New York Times Book Review). “As a series of images, the book exerts a seductive, arcane power, rather like a deck of tarot cards, every page seething with lavish, cryptic innuendo. Yet, as a narrative it is wanting…. The symbols here, although entrancing individually, feel at once overdetermined and underpurposed. They never fully cohere into a satisfying web.”

“One of the most consistent pleasures of Levy’s fiction is her complete resistance to unthinking characters, unthinking female characters in particular,” notes Eimear McBridge (New Statesman). She also voices a quibble:

Levy deftly twins the mother-daughter, physical-emotional paralysis from the outset, too, so the deep sense of filial bondage is clear. Yet it is Sofia’s obvious understanding of the reasons behind her failure to take on any of the responsibilities that might be expected of an intelligent, well-educated, 25-year-old woman that eventually creates a certain frustration with the narrative. She knows, and we know she knows, what both the problem and the solution are, almost from the first page. It is difficult to remain patient with a woman who colludes in overly extending her own adolescence. Nevertheless, the way Levy draws the other strands together makes up for this irritation.

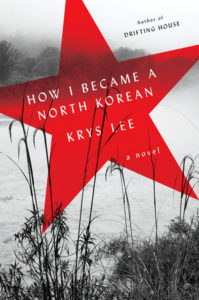

Krys Lee, How I Became a North Korean

Lee, who teaches at Yonsei University in South Korea, is the author of a much lauded story collection, Drifting House, and recipient of the Rome Prize and the Story Prize Spotlight Award. How I Became North Korean already has made the long list for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize.

Katie Cunningham (Christian Science Monitor) responds with praise. “Lee (who currently lives and works in Seoul) offers a raw take on the China-North Korea conflict, examining what ‘ally’ and ‘enemy’ seem to be in the eyes of the next generation. She also weaves questions of racism, religion, sexism, and sexual orientation throughout, giving the novel a meatier feel. It’s also impossible to read this novel without remembering – even as the teen protagonists push the limits on the unthinkable to do what they need to do to survive – that many real-life refugees have faced similar tough decisions and horrors in order to escape.”

Connie Ogle (Miami Herald) concludes:

Readers of Adam Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Orphan Master’s Son should relish this revelation of yet another facet of North Korean life. How I Became A North Korean doesn’t quite reach that novel’s mighty scope, but it’s an intense, unforgettable, compassionate study of human resilience. “A person can get used to almost anything in order to survive,” Jangmi says. “That was what China taught me.” What Lee teaches us is that there is hope in the most desperate of circumstances, that the human spirit can still sputter to life after the worst has happened.

“Lee’s story throws light on a place we know little about, in heart-wrenching, lyrical detail,” writes Estelle Tang (Elle).

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.