Five Books Making News This Week: Legends, Looting, and Lambs

Don DeLillo, Tom Burgis, Lydia Millet, and More

As short story month begins, we are reminded of two masters of the form. Andrea Barrett wins the Rea Award for the Short Story, cited by judges T.C. Boyle, Bill Henderson (Pushcart Press founder/editor) and Karen Shepard for “a body of stories that like all great fiction expands our knowledge, brings us more fully into contact with the suffering of others, and supplies intense and gorgeous pleasure.” And Joy Williams is honored with the 2016 PEN/Malamud Award for Short Fiction. “Joy Williams’ short stories are, sentence to sentence, incandescent, witty, alarming, often hilarious while affecting seeming inadvertence (but not really) in their powerful access to our human condition,” writes Richard Ford of the selection committee. The Edgar Award for best novel goes to Lori Roy, for Let Me Die in His Footsteps. (Viet Thanh Nguyen, newly minted Pulitzer winner, picks up an Edgar for Best First Novel for The Sympathizer). Applause comes quickly for Don DeLillo’s new novel. Geoff Dyer’s latest essay collection prompts discussion of his inimitable tone, and early response to Lydia Millet’s new novel applauds her genre-shifting genius. And there’s news from abroad: New York Times reporter Robert F. Worth tracks the aftermath of the Arab Spring, and the Overseas Press Club honors The Looting Machine by Tom Burgis, who has reported from Africa for the Financial Times since 2006.

Don DeLillo, Zero K

A new novel from DeLillo? Cause for critical celebration. Although he tells the Wall Street Journal’s Brenda Cronin he “pays little attention to reviews,” and expresses regret that he is “not a better pool player.”

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) calls Zero K DeLillo’s “most persuasive since his astonishing 1997 masterpiece, Underworld, and “kind of bookend to White Noise (1985): somber and coolly futuristic, where that earlier book was satirical and darkly comic.”

She concludes:

All the themes that have animated Mr. DeLillo’s novels over the years are threaded through Zero K—from the seduction of technology and mass media to the power of money and the fear of chaos. This novel does not possess—or aspire toward—the symphonic sweep of Underworld; it’s more like a chamber music piece. But once the novel shakes off its labored start, Zero K reminds us of Mr. DeLillo’s almost Day-Glo powers as a writer and his understanding of the strange, contorted shapes that eternal human concerns (with mortality and time) can take in the new millennium.

“His most funereal novel,” “a slim, grim nightmare in print,” “Disney’s Frozen for the hospice crowd” writes Ron Charles (Washington Post). Charles calls the Convergence—DeLillo’s cryogenic facility in the desert near the capital of Kyrgyzstan “the most ambitious life-after-death scheme since the pharaohs built the pyramids.” Charles concludes, “The whole novel offers up phrases that are sure to be recycled in reverent tweets for years. From ‘the soporifics of normalcy’ to ‘the numbing raptures of the Web,’ Zero K captures us ‘trapped in our own obsessive clamor.’”

“So what are we to make of the naked brutality of Zero K?” asks Meghan Daum (The Atlantic). “The severed heads, the broken bodies, the grisly images on the screens? If some 30 years ago DeLillo suggested, in White Noise, that the primal human terror is the fear of death, Zero K appears to be a novel about the fear of life…The big prize is the realization that in dying (even, God forbid, the old-fashioned, nonfrozen way), we’re not really going to miss much. On the contrary, given what lies in store, we’re going to want to miss most of it.”

Charles Finch (Chicago Tribune) finds Zero K “brilliant and astonishing,” “transcendent,” and “excellent in many ways”:

It’s full of DeLillo’s amazing inimitable scalpel perceptions; it’s fluent in the ideas we’ll be talking about 20 years from now; and it reads like a book a millennial could have written. Given that its author is nearly 80, that’s dumbfounding. But the book’s most satisfying element isn’t its high standard of execution, it’s the slight feeling of unbending in it, the scope and generosity of its conclusions. Any rock in the desert will “outlive us all, probably outlive the species itself,” Jeffrey realizes. Merely to survive is nothing without being able to say what it was like.

Geoff Dyer, White Sands

As a prelude to the latest collection of his essays, ostensibly arranged around the theme of travel, Dyer gives up his secret to Tishani Doshi (The Hindu): “I’m so interested in what [D.H.] Lawrence calls nodality, not just in this book, but I think it’s one of the things that appears in all of the books I’ve written. More and more, I’m looking for a place that has that thing of the temporal manifesting in the spatial, a sense of history in geography. And although I’m not going around consciously with my antennas up, like a Geiger counter, I’m always drawn to those places. Always.”

“You must…get used to Dyer’s tone, which is persnickety and unenthusiastic,” Jane Smiley (Los Angeles Times) warns. But she’s a fan: “His virtue is not the whole-hearted embrace of experience and exotic locales but the parsing of degrees of disappointment. He also doesn’t pretend to be heading anywhere, but then White Sands turns into a memoir and becomes unexpectedly moving.”

James Sullivan (San Francisco Chronicle) also comments on Dyer’s tone: “What is the point of anything, really? That’s the basis for much, maybe most, of the comedy in this world. And that’s the basis for the singularly entertaining oeuvre of the writer Geoff Dyer, who takes a headlong interest in things—ideas, places, works of art—only to fall back on his default position: prone, and despairing.”

Lydia Millet, Sweet Lamb of Heaven

The author of 10 works of fiction (and three YA books) is a genre shape shifter. Her new novel, which starts with a runaway mother and evolves in surprising directions, evokes wonder.

“For a novelist who has been a Pulitzer Prize finalist, Lydia Millet is not as well-known as she deserves to be,” writes Lisa Zeidner (Washington Post). “The obstacle to broader popularity is most likely her category-defying voice, a slippery blend of lyricism and absurdist humor. She asks profound philosophical questions, yet has a direct, confiding style that doesn’t broadcast high seriousness…her ambitious new novel is part fast-paced thriller, part quiet meditation on the nature of God.” Zeidner concludes:

Millet deserves to be celebrated for staking out territory in which the novel can ruminate about current scientific developments. But that makes her work sound dry or polemical, which it is decidedly not. It’s exuberant and playful. That Millet can smuggle her original insights into a structure featuring a rollicking kidnapping plot and deliciously well-drawn characters makes her achievement even more remarkable.

Sweet Lamb of Heaven “confounded me, delightfully so,” notes Laura Lippmann (New York Times Book Review). Lippmann notes of Anna, Millet’s narrator: “It is Anna’s voice—cool, intelligent, passionate, contradictory—that makes this novel so affecting. I resisted it initially because I was overwhelmed by my sense of dislocation, my uncertainty about where we were headed. But how I missed it when it was gone, how I yearned for it to speak to me again.”

Robert F. Worth, A Rage for Order

New York Times foreign correspondent Worth traces events from the 2011 Arab Spring forward, offering rare insights along the way. Nicholas Kristof tweets, “Rave review of Robert F. Worth’s new book about the Middle East, A Rage for Order.”

Kenneth M. Pollack (New York Times) is unequivocal: “This is the book on the Middle East you have been waiting to read. A Rage for Order tells the story of the 2011 Arab Spring and its slide into autocracy and civil war better than I ever could have imagined its being told. The volume is remarkably slender for one of such drama and scope—beautifully written, Worth’s words scudding easily and gracefully across the pages. It is also a marvel of storytelling, with the chapters conjuring a poignancy fitting for the subject.”

“Worth does not offer any advice for the State Department or any forecasts of what will come next in the Arab world,” writes Adam Kirsch (Tablet). “Rather, Worth, a longtime foreign correspondent for the New York Times, offers a series of snapshots and profiles from the Arab Spring and its aftermath, showing how events unfolded at the scale of individual lives. This is an important service, since when we talk about the Middle East, we tend to use large religious and ideological abstractions—Sunnis and Shiites, secularists and Islamists. Worth brings those words back to their roots in the lives of real people, showing how people who never dreamed of making war or revolution ended up being unmade by them.”

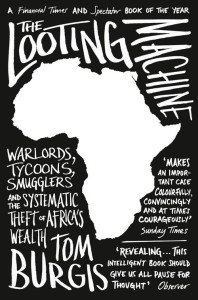

Tom Burgis, The Looting Machine

Thursday night the Overseas Press Club presents its award for best nonfiction book on international affairs to Tom Burgis’s The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth. (It’s due out in paperback July 4). The judges cite the book for its “exceptionally detailed reporting on a critical topic: how resource-rich African countries have been looted by their political leaders working hand-in-hand with international corporations. Burgis carries out remarkable on-the-ground investigations to identify the government and corporate officials who, in country after country, collude to amass tremendous fortunes while leaving their citizens impoverished and powerless. The book is a must-read for those eager to understand the problems plaguing a wide swath of Africa today.”

Howard W. French (Foreign Affairs) lauds the book, writing that Burgis “brings the tools of an investigative reporter and the sensibility of a foreign correspondent to his story, narrating scenes of graft in the swamps of Nigeria’s oil-producing coastal delta region and in the lush mining country of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, while also sniffing out corruption in the lobbies of Hong Kong skyscrapers, where shell corporations engineer murky deals that earn huge sums of money for a host of shady international players. Although Burgis’ emphasis is ultimately on Africa’s exploitation by outsiders, he never loses sight of local culprits.”