Five Books Making News This Week: Heavyweight Season

#FerranteFever, #Franzenfreude, Sir Salman, Clegg's Debut

Three heavy hitters hit the shelves this week. Ferrante fans launched The Story of the Lost Child with midnight champagne September 1 in Brooklyn and reviewers sent out cheers from all directions. That same day, Franzen started the life of Purity, which begins and ends in California, in his newly adopted hometown of Santa Cruz. Salman Rushdie’s updated Arabian Nights arrived, as did Bill Clegg’s first novel, already longlisted for the Man Booker prize.

The Story of the Lost Child, Elena Ferrante

The cult of Ferrante went into overdrive this week, as the conclusion of her Neapolitan series hit the stores and critical adoration reached a crescendo.

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) compares Ferrante to Alice Munro and Doris Lessing. Her Neapolitan novels are “utterly distinctive,” she writes, “immersing us not just in a time and place, but deep within the psychological consciousness of its narrator, Elena (who, not coincidentally, shares the first part of her creator’s pen name). These four novels have the symphonic intricacy of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time and the intensity and sense of place of Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet. They are ingeniously plotted, with clues to thriller-like disappearances deftly and invisibly planted (beginning in the first volume, with the vanishing of a 60-something Lila, and circling back in time to the even more devastating loss of a child), and at the same time, rooted in an understanding of their two heroines that is utterly visceral and immediate.”

Laura Miller (Slate) likens Ferrante’s saga of female friendship to Mary McCarthy’s The Group, Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything, and Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, and concludes “class and identity strike me as the true central concerns of Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, not female friendship or even womanhood itself.” As the Neapolitan novels progress, she adds, “the books come to seem less and less a work of realist autobiographical fiction about female friendship and more and more a covertly mythic tale of the creation of a self through agonizing division and uneasy reintegration.”

Joan Acocella (The New Yorker) describes the Neapolitan novels in toto as “the most thoroughgoing feminist novel I have ever read.” Of the friendship between Lena and Lila, she writes, “…’love’ is too narrow a word for it. The two envy each other, compete with each other. They help and gravely harm each other. In The Story of the Lost Child, they get pregnant at the same time… Lena’s family lives upstairs from Lila’s, and their children eat and sleep now at one apartment, now at the other.”

“Finishing the last volume, I felt like I’d entered, for a time, another existence,” writes Darcey Steinke (Los Angeles Times). “Like Anna Karenina, Lila and Elena are volatile, full of desire and rage. They too break domestic conventions, but it thrills me that instead of killing them off, Ferrante allows them, in all their chaos and pain, to thrive.”

Charles Finch (Chicago Tribune) is enthusiastic: “What words do you save? Here’s your chance to bring them out, like the silver for the wedding of the first-born: genius, tour de force, masterpiece. They apply to the work of Elena Ferrante…” Finch uses his own crowning phrase for the Neapolitan quartet: “The greatest achievement in fiction of the post-war era.”

Purity, Jonathan Franzen

The label “Best American Novelist” and his widely reported, sometimes intemperate public remarks have left the lingering effects we know as Franzenfreude. Purity’s reviews range from glowing to dismissive.

Maureen Corrigan (NPR) finds Purity lacking: “You’ve got to be a Dickens to be able to command a cavalcade of stories and characters without numbing your audience. Some contemporary novelists like, say, Zadie Smith, David Mitchell and Donna Tartt have pulled it off, but, despite the Dickensian echoes of his heroine’s name, Franzen can’t meet such great expectations in Purity.”

“For all its extravagant ambition, the book is full of self-indulgent nonsense,” writes Roxane Gay (NPR.org). Franzen is not just “reaching for the zeitgeist,” she concludes. “He is offering up an earnest, albeit rather narrow and privileged assessment of the world we live in and a demonstration of how the more we are able to know about others, the less we know about ourselves. Unfortunately, the shame of this novel is that purity is largely found not in the storytelling but in the author’s passive-aggressive contempt for nearly all his characters.”

Yvonne Zipp (Christian Science Monitor) calls Purity “the best book the prodigiously talented novelist has written—funnier, looser, with more care for his characters and nary a hectoring lecture on saving songbirds in sight.”

Nell Zink’s review, posted in mid-July on N+1, breaking the embargo, is back. “Plenty of people think his books are no fun,” she writes. “And it’s true, they’re mostly dense, discomfiting portrayals of disappointing people. But Purity is fun…”

Colette Bancroft (Tampa Bay Times) assesses Purity as a better book than Freedom: “Purity is not a litmus test, it’s a notable literary accomplishment—and it’s also the most fun I’ve ever had reading a Franzen novel.”

Urmila Seshagiri (Los Angeles Review of Books) addresses Franzen’s gender issues: “What darkens Purity and weakens its realist musculature is Franzen’s atavistic treatment of male and female character. In Purity’s calculus, men are predators, women prey, and rape an inevitable aspect of being. We are asked to regard the male characters’ sexual urges—including rape, incest, pedophilia, the consumption of brutal pornography, and acts of murder—as biological prerogatives unjustly targeted by 20th-century feminism.”

Rayyan Al-Shawaf (Chicago Reader) is in the negative camp: “The domestic drudgery and bickering in which Franzen mires his characters, the ferocious neuroses with which he saddles most of the women (including, to a certain extent, Pip; Leila, Tom’s current girlfriend, is the only one who seems well-adjusted), and the interminable recounting of their personal histories combine to render Purity, as a whole, indigestible.”

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, Salman Rushdie

Critics seem divided over the twelfth novel from Rushdie, whose Midnight’s Children was named the “Best of the Bookers” in 2008, with high praise and low blows.

Ursula K. Le Guin (The Guardian) calls Rushdie “our Scheherazade, inexhaustibly enfolding story within story and unfolding tale after tale with such irrepressible delight that it comes as a shock to remember that, like her, he has lived the life of a storyteller in immediate peril,” hails his “fractal imagination: plot buds from plot, endlessly,” and proclaims his new novel “a fantasy, a fairytale—and a brilliant reflection of and serious meditation on the choices and agonies of our life in this world.”

Carolina De Robertis (San Francisco Chronicle) admires Rushdie’s “tremendously inventive and timely novel.” She has a quibble or two: “Early on, there is an overabundance of female characters repetitively described as “young” and “beautiful,” who inexplicably offer themselves erotically to older men. And, later, as the narrative web builds and expands, there are moments where the fabulist flights feel slightly cartoonish. “But these issues burn away in the great blaze of this novel, which draws power from its uncomfortable proximity to our real world.”

Ron Charles (Washington Post) mentions the years of the fatwa against Rushdie for The Satanic Verses: “As terrifying as that ordeal undoubtedly was, Rushdie has now elaborately mythologized it by the light of Aladdin’s lamp, recasting the tension between superstition and reason as a series of magical tales. He never calls anybody out by name, but it won’t take a jinni to tell you who belongs to that ‘murderous gang of ignoramuses’ who devote themselves to ‘the art of forbidding things.’”

Rushdie “seems to be having fun with the adult content,” writes Carolyn Kellogg (Los Angeles Times). “He works in jokes about the sexual appetites of his jinn, brings alive dark corners of Manhattan, explores misplaced love, and creates a good-versus-evil battle that’s firmly grounded in philosophy.” The novel, she concludes, is “an amusement park of a pulpy disaster novel that resists flying out of control by being grounded by religion, history, culture and love.”

Ann Hulbert (The Atlantic) relishes Rushdie’s “bracing dose of self-mockery,” which, she writes, “helps his antic magic and earnest message go down well.” But, she adds, “his most astute, and poignant, move is to pair one catalyst of the turmoil, a chameleon jinni of many names (Princess Aasmaan Peri, Skyfairy, Dunia, and the Lightning Princess), with a feet-in-the-dirt gardener fed up with fairy stuff.”

Ellen Akins (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) is upbeat: “There are monsters who slip through wormholes, or slits between worlds; there are battles and set pieces, in Fairyland and on Earth; there are sometimes ridiculous, sometimes hilarious comic turns; stories within stories; riddles within tales within legends. And there is Salman Rushdie, manic Scheherazade, assuming all the voices, playing all the parts, making a mad kind of sense of it all.”

Charles Finch (Chicago Tribune) uses terms like “very bad,” “terribly boring” and “incompetent.” Jenny Hendrix (The New Republic) terms the novel “so baffling that you have to wonder whether it’s some kind of a prank.”

Michael Upchurch (Seattle Times) finds that Rushdie’s new novel “begins and ends on such a perfect note that it leaves you wondering why so much of the book feels so slapdash.”

Did You Ever Have a Family, Bill Clegg

Being longlisted for the Man Booker prize weeks before publication date guaranteed lots of critical attention for this mournful first novel, which takes its title from a line in Alan Shapiro’s poem, “Song and Dance.”

“Don’t be put off by its schmaltzy title or similarities with the tragic 2011 Christmas morning fire that was headline news for weeks after taking the lives of an advertising executive’s parents and three daughters in her Shippan Point, Conn., home,” writes Heller McAlpin (Los Angeles Times) of Clegg’s first novel. “Although its inspiration may be ripped from the headlines, Bill Clegg’s beautifully written debut novel, Did You Ever Have a Family, goes way deeper than lurid banner news accounts to illuminate how grief, guilt, regrets and the deep need for human connection are woven into the very flammable fabric of humanity. The most sensational thing about this novel is how it manages to accomplish all this without a whiff of schadenfreude, prurience or mawkishness.”

Clegg earns praise from the Washington Post’s Ron Charles: “From the first page, Clegg writes about sorrow with such authenticity and dignity that we’re immediately willing to trust him.”

“Clegg has attempted something daring,” writes Jason Sheehan (NPR.org). “And the wonder of it is how often his experiment succeeds—and how strange the view of a terrible thing can be depending on the angle from which you view it.”

Clare Clark (The Guardian) has a timely take: “In the world of serious literary fiction, the conflation of bleakness and profundity means that too often the novels declared the most important are those that plumb new depths of human cruelty and suffering. Two of the 13 books on this year’s Man Booker prize longlist explore the trauma of childhood abuse, a third a savagely dystopian London, but it is their fellow nominee Bill Clegg’s debut novel that would appear at first sight to blow his competition for grimmest subject matter out of the water.”

Kaui Hart Hemmings (New York Times Book Review) calls Clegg’s novel “masterly” and “thoughtful.” Tom Zelman (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) adds his admiration for “a quiet and beautifully written novel that will keep readers turning the pages.”

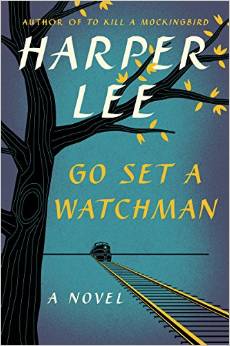

Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee

After a gazillion reviews (with the earliest gathered here and here) plus interviews, alerts and shares since its July 14 publication date, Go Set a Watchman is a top book checked out at public libraries, according to Quartz’s David Yanofsky.

And the New York Times reveals the ground-breaking nature of that Atticus Finch push alert: mobile news triumphed over embargo-breaking front-page headlines: “We send a push notification. The phone beeps, buzzes, vibrates, lights up and there’s a message on a locked home screen… It allows us to, for all intents and purposes, tap the user on her shoulder. That’s very, very powerful.”

Feature image: detail from the UK cover of Did You Ever Have a Family.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.