Five Books Making News This Week: Floods, Ponds, and Grief

Angela Palm, Claire-Louise Bennett, Jacqueline Woodson, and More

Phillip Glass wins the Chicago Tribune Literary Award for his memoir Words Without Music. Heartland Prizes go to Jane Smiley for Golden Age (fiction) and Margo Jefferson for Negroland (nonfiction). T.C. Boyle wins the inaugural $25,000 Mark Twain award for a fictional work that “best captures a distinctly American voice,” for his novel, The Harder They Come (Ecco). Runners-up: Welcome to Braggsville by T. Geronimo Johnson and The First Bad Man by Miranda July. Colson Whitehead’s Oprah pick, The Underground Railroad gathers speed (and he’s on President Obama’s summer reading list, as tweeted by Reuters White House Correspondent Jeff Mason). National Book Award winning YA author Jacqueline Woodson’s first adult novel is sheer poetry; Teju Cole’s essays, collected, exhibit a wide-ranging intelligence, and first books by Irish-born Claire-Louise Bennett and Indiana-born Angela Palm prove they are writers to watch.

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

For a second week, Whitehead’s story of Cora, a slave who follows a path toward freedom via a railroad that is literal and underground, has critics raving.

“With this novel, Colson Whitehead proves that he belongs on any short list of America’s greatest authors — his talent and range are beyond impressive and impossible to ignore,” writes Michael Schaub (NPR). “The Underground Railroad is an American masterpiece, as much a searing document of a cruel history as a uniquely brilliant work of fiction. And it is, finally, an impassioned cry for the soul of a country that still struggles to embrace the promise of its humanity: ‘The only way to know how long you are lost in the darkness is to be saved from it.’”

Whitehead’s novel, writes Connie Ogle (Miami Herald), is “a thrilling, relentless adventure, an exquisitely crafted novel that exerts a deep emotional pull. It’s an alternate history with a bite and a heart. But Whitehead’s greatest skill is that he also forces us to consider the messy, ugly state of race relations today the further we immerse ourselves in Cora’s nightmare worlds.”

“America,” he writes, “is a delusion, the grandest one of all. … This nation shouldn’t exist, if there is any justice in the world, for its foundations are murder, theft and cruelty. Yet here we are.” True. But a book like The Underground Railroad — a masterpiece, let’s just say it — can put our tattered, ugly past in perspective and maybe help us forge some kind of better future.

“The Underground Railroad makes it clear that Whitehead’s omnivorous cultural appetite has devoured narratives of every variety and made them his own,” writes Laura Miller (Slate). “This novel, like much of his work, has the flavor of Ellison’s skepticism—but it’s also redolent of the propulsive, quasi-allegorical quest plot of Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series. Think of The Underground Railroad as the novel where the spirits of two great American storytellers meet in a third. What makes Cora’s mission existential rather than epic is that she just wants to be a human being in a nation hellbent on denying her that status.”

Jacqueline Woodson, Another Brooklyn

Woodson’s 32nd book is her first novel for adults, after 31 children’s and Young Adult books, including the National book Award winner, Brown Girl Dreaming. Critics respond to its poetic style.

“Another Brooklyn is a short but complex story that arises from simmering grief,” writes Ron Charles (Washington Post). “It lulls across the pages like a mournful whisper.”

He concludes: “It’s as much as a compliment as a complaint to say that I wish the story were fuller. There’s enough material here for a much longer novel, and, though Woodson’s prose is always carefully constructed, she’s sometimes so elliptical that complicated issues are illuminated only obliquely. But that’s the real attraction of this novel, which mixes wonder and grief so poignantly. Woodson manages to remember what cannot be documented, to suggest what cannot be said. Another Brooklyn is another name for poetry.”

Another Brooklyn, writes Nichole Perkins (Los Angeles Times), “joins the tradition of studying female friendships and the families we create when our own isn’t enough, like that of Toni Morrison’s Sula, Tayari Jones’ Silver Sparrow, and Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lorde. Woodson uses her expertise at portraying the lives of children to explore the power of memory, death and friendship. Even when what was good turns sour, it can fuel the rest of our lives, in ways we never think to acknowledge.”

Bliss Broyard (Elle) writes, “Written in spare vignettes, sometimes with only a few sentences to a page, Another Brooklyn can feel like living in someone else’s dream. Underneath each moment lies a network of connected memories, illuminating, one after another, an entire life.”

Teju Cole, Known and Strange Things

Born in the U.S., raised in Nigeria, Cole is a novelist (Open City, a National Book Critics Circle fiction finalist), photographer, art historian, essayist, Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College and photography critic of the New York Times Magazine. His new collection begins with his pilgrimages to the Swiss community where Baldwin wrote an iconic essay “Stranger in the Village” and to W. G. Sebald’s grave, and includes his essay “The White Savior Industrial Complex,” which originated on Twitter. Response: glowing reviews.

In Cole’s first collection of nonfiction, “journeys through all the landscapes he has access to: international, personal, cultural, technological and emotional,” notes Claudia Rankine (New York Times Book Review), “the world belongs to Cole and is thornily and gloriously allied with his curiosity and his personhood.” “On every level of engagement and critique,” she concludes, “Known and Strange Things is an essential and scintillating journey.”

“Africans are generally not expected to be experts on non-African subjects,” writes Pettina Gappah (The Guardian). “We are perennially other people’s subjects, never the anthropologists, and when we show that we can return the gaze with equal intensity, that we can also glory in expertise that goes beyond the innate knowledge of our own worlds, the response is often similar to Naipaul’s: ‘He’s very good, he speaks so well, he speaks well.’ So I am grateful that Cole has quietly and calmly asserted his right to write in the key most harmonious to him, and to do so at the deepest level. He has asserted the right to write on Brahms and Kofi Awoonor, Derek Walcott and Tomas Tranströmer, Sebald and Wole Soyinka, Wangechi Mutu and Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Malick Sidibé and Krzysztof Kieslowski. The essays demonstrate the transformative power of communion with gifted and committed master craftsmen and women who have given, and continue to give, the very best of themselves, and thus raise their achievement from the merely competent to the sublime.”

Elizabeth Rosner (San Francisco Chronicle) concludes: “Most poignant of all is Cole’s epilogue, in which he depicts his temporary yet terrifying experiences of papillophlebitis (or ‘big blind spot’), followed by restored (though myopic) sight. Linking this to Virginia Woolf’s ‘epiphanic moments that intermittently illuminated the gloom,’ he revisits his overarching metaphor, with the ‘insurgent area of darkness’ taking over and clearing up, and his expectation ‘that it will happen again, and again, until it is supplanted by something worse, as it was written.’”

Claire-Louise Bennett, Pond

Bennett’s first book of fiction was initially published as a story collection by Stinging Fly Press in Ireland, then reprinted in the U.K. by Fitzcarraldo. Now it’s out as a first novel from Riverhead. However its form is defined, reviewers find Pond enthralling.

“Though the title and some of the narrator’s observations deliberately reach back to that other famous literary pond, Bennett’s Pond is an altogether different body of water from Henry David Thoreau’s Walden,” writes A.N. Devers (The New Republic). “Pond is not about a prickish man throwing out the creature comforts of society for a brief and beautiful proto-hippy experiment—as the New Yorker’s Kathryn Schulz hilariously detailed last year in her ponderance on Thoreau, bitingly titled, ‘Pond Scum’—nor is it about the same privileged man who lived in a shack but likely didn’t have to do his laundry, as Rebecca Solnit elucidated in her Pushcart Prize-winning Orion essay. Oh no, this is a pond as it relates to the overlooked, under-described, and often dismissed life of a woman as herself, alone in a domestic realm but rarely lonely.”

Meghan O’Rourke (New York Times Book Review) calls Pond “a sharp, funny and eccentric debut…one of those books so odd and vivid that they make your own life feel strangely remote.” “Somehow,” she adds, “Bennett has written a fantasy novel for grown-ups that is a kind of extended case for living an existence that threatens to slip out of time. Such a life, Bennett suggests, is more actual than list-laden, ego-driven, ‘successful’ adulthoods.”

“Like Lydia Davis, Bennett, who is from the southwest of England, takes a state of mind closely associated with madness and places it in settings that are utterly domestic, mundane,” writes Jia Tolentino (NewYorker.com). “The result is fervid and fearful; at times, Pond recalls works by Knut Hamsun and Samuel Beckett, in which characters are more obviously forced into states of isolation. At other points, the book evokes the cottage hymns of Katharine Tynan, the pure formal eccentricity of Emily Dickinson, and the dread-laced, detonating uncertainty of W. B. Yeats.”

Meaghan O’Connell (New York) concludes that Pond is “the female answer to Knausgaard.” “It feels, to me, if by nothing else but instinct, like a distinctly female consciousness, which makes the Knausgaard comparison that much more pointed. It is a short, concise, cutting book. It is 195 pages, not 3,600 pages, not six volumes. The experience of reading these books side by side, as I did inadvertently, is incomparable except for the thing that is most remarkable about them both: They offer, in different styles, and at different lengths, an almost-painful intimacy with the reader.”

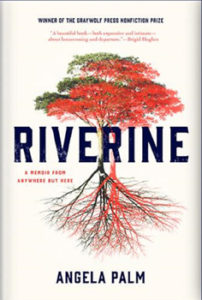

Angela Palm, Riverine

The 2016 winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize describes a girlhood in an Indiana flood zone, an impoverished neighborhood in which a neighbor boy becomes a beloved anchor, until he’s jailed for murder. Palm’s first book gathers laurels from critics.

Riverine, writes Beth Kephart (Chicago Tribune), “has seeped into my blood and left me messy inside — alerted, diverted, and scrambling to get a hold on time.” After comparing her to Mary Karr, J.R. Moehringer, Jo Ann Beard and Annie Dillard, Kephart concludes:

Palm stretches the envelope of truth on the page.

She experiments with (then sometimes repeats) essayistic forms. There are returning metaphors, recurrent scenes, displacements. There are essays where, perhaps, Palm pushes the digressive weave too far…. But there is volumetric power here. Sizable intrigue in the sentences. Bold declarations that (as all memoir must) destabilize the reader and paralyze easy judgment on both the life lived and the words chosen. Angela Palm has left the river and returned to it. Angela Palm has arrived.

“Palm emerges from these pages as someone who holds on firmly to the first boy she ever fell in love with, someone who forges a new life for herself while never forgetting where she comes from,” writes Michele Filgate (Washington Post). “There’s a flickering beauty to her stubbornness, like the reflection of late afternoon sunlight in a river.”

The Publishers Weekly book of the week review notes, “Palm probes deeply into the family and small-town stories, which instilled such a deep sense of place in the author. She becomes fascinated with theories of criminal justice—taking college classes on the subject, reading local police blotters, and watching crime shows on television to better understand the how and why of what happened to her friend. All in all, this is a memoir to linger over, savor and study.”

Watch: Jacqueline Woodson talks to Lit Hub at the National Book Awards on writing what matters instead of what sells.