Five Books Making News This Week: Detectives, Demagogues, and Dystopias

Tana French, Volker Ullrich, Michael Helm, and More

The first week of autumn brings a rush of news on the literary front. Brit Bennett (The Mothers), Yaa Gyasi (Homegoing), Greg Jackson (Prodigals), S. Li (Transoceanic Lights) and Thomas Pierce (Hall of Small Mammals) make the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 list. PEN America names new board members Six books are shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize, which rewards “fiction that breaks the mould or extends the possibilities of the novel form,” including Rachel Cusk’s Transit, Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk, Eimear McBride’s The Lesser Bohemians (her first novel, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, won the award in 2013), and Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun. PEN American Center adds Markus Dohle, CEO of Penguin Random House, to its board, along with poet and memoirist Saeed Jones and novelists Dinaw Mengestu and Hanya Yanagihara. New biographies trace Hitler’s “ascent from ‘dunderhead’ to demagogue,” pianist Van Cliburn’s triumphant assault on Moscow, and the life and work of “Lottery” author Shirley Jackson. Novelists Tana French and Michael Helm transcend genre.

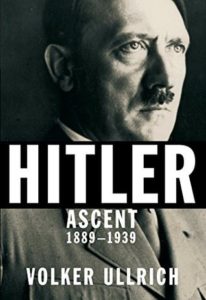

Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939

Michiko Kakutani’s review of the first of two volumes of a new Hitler biography shakes up the Twitterverse. “It’s true that the review didn’t name Trump—or even allude to the 2016 U.S. presidential race” points out the Washington Post’s Aaron Blake. “But it came across to more than a few readers as an intentional, point-by-point comparison of Hitler’s rise and Trump’s.” Within hours, the book is a bestseller, writes its translator, Jefferson Chase.

“Mr. Ullrich offers a fascinating Shakespearean parable about how the confluence of circumstance, chance, a ruthless individual and the willful blindness of others can transform a country—and, in Hitler’s case, lead to an unimaginable nightmare for the world,” writes Michiko Kakutani (New York Times).

“Hitler’s rise was not inevitable, in Mr. Ullrich’s opinion,” she notes.

There were numerous points at which his ascent might have been derailed, he contends; even as late as January 1933, “it would have been eminently possible to prevent his nomination as Reich chancellor.” He benefited from a “constellation of crises that he was able to exploit cleverly and unscrupulously”—in addition to economic woes and unemployment, there was an “erosion of the political center” and a growing resentment of the elites. The unwillingness of Germany’s political parties to compromise had contributed to a perception of government dysfunction, Mr. Ullrich suggests, and the belief of Hitler supporters that the country needed “a man of iron” who could shake things up.

Neil Gregor (Wall Street Journal) parses the Hitler biography lineage, then asks, “Where, then, does Mr. Ullrich’s account fit into this crowded landscape? What, if anything, does it add?” He concludes:

Mr. Ullrich is a journalist rather than an academic, which partly explains one of the book’s many positive features—its remarkable fluency and readability, which has been ably captured in an excellent translation by Jefferson Chase. Avoiding the often deadening prose of his German academic colleagues, Mr. Ullrich has produced an immensely engaging book: It can be recommended without hesitation to those who seek an approach that blends the personal focus of biography with a lively, informative account of the political background.But this is no triumph of style over substance. Mr. Ullrich knows his stuff.

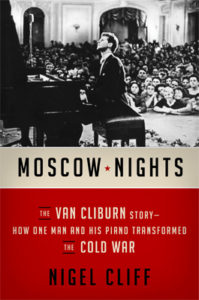

Nigel Cliff, Moscow Nights

A new biography of the legendary pianist casts Cliburn as a secret weapon in the Cold War.

“Nigel Cliff, as given to emotional flourishes in his prose as Cliburn was at the piano, blends Cold War history and biography,” writes Ann Hulbert (The Atlantic). “Vivid details are his forte as he evokes the man who went on to inspire more swooning at the Soviet Union’s first international piano and violin competition, in 1958. It was half a year after Sputnik, and though the contest seemed rigged against the U.S., ordinary Soviets went crazy for Cliburn.”

James Barron (New York Times Book Review) notes that Cliff did not turn up evidence that Cliburn ever passed secret diplomatic dispatches back and forth. “…as he writes, Cliburn may have been ‘courted by presidents and Politburo members,’ but he was also ‘watched by the F.B.I. and K.G.B.’ Mostly, Cliburn served as a relief valve, easing the pressures his audiences felt.”

Laurie Hertzel (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) praises Cliff:

Cliff does a magnificent job of setting things in historical context, breaking away from Cliburn’s story to vividly recount the last hours of Stalin (his guards were afraid to check on him, “scared at what might have happened and even more scared that they might have to disobey his orders not to disturb him” ), as well as the rise of the “voluble, roly-poly” Nikita Khrushchev.

Cliff has a great eye for entertaining stories and lively anecdotes (all footnoted within an inch of their lives — a good thing), and he seems genuinely fond of everyone he writes about (even Stalin, sort of). At times, Khrushchev and his colorful escapades threaten to steal the book from the more one-dimensional Cliburn.

Ruth Franklin, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life

Franklin’s biography of Jackson illuminates the author’s writing process as well as her complicated emotional life.

“Rare is the author biography (Blake Bailey’s study of Richard Yates is another) that so thoroughly explores and illuminates the subject’s writing itself,” writes Megan Abbott (Barnes and Noble Review). “Franklin offers inspired discussion of every novel, both memoirs, and many of the major stories. It is with the same keen literary-investigative eye that Franklin makes astute but measured connections between Jackson’s work and life._ One illuminating example is a discussion of two letters Jackson wrote but never sent. The first occurs after Jackson receives a note from her mother—a source of lifelong anxiety for Jackson—criticizing her appearance after seeing her daughter photographed in a Time magazine profile. Jackson’s initial, unsent reply demands her mother cease her “unending” critiques. Franklin finds a canny parallel when, early in their relationship, Jackson wrote Hyman an angry, broken letter after he confided an infidelity. Once more, she never sent it, never let her pain reach its source. Both mother and husband provoke her rage and break her heart, yet Jackson stifles herself — not on the page, but the pages never reach their intended recipient. Her fiction, however, is where those feelings find their home.

Scott Bradfield (Los Angeles Times) writes, “Franklin’s biography of Jackson provides a well-written, well-considered and enjoyable opportunity for those of us who recall the pleasures of reading Jackson to go out and enjoy her all over again; it also helps make up for the poor scholarly attention her novels and stories have received since her death.”

“As Franklin’s subtitle, ‘A Rather Haunted Life,’ suggests, Jackson also had a tragic private life,” writes Charles McGrath (New York Times Book Review). “She was a fragile, damaged and often desolate person, subject not just to the trials that beset ambitious women of her generation but to torments all her own.”

Tana French, The Trespasser

“I like historical true crime, the kind that uses the crime as a window into the time and place where it happened,” French writes in the New York Times By the Book column. Her talent for creating authentic characters in crime fiction has built her fan base from book to book.

“It has become increasingly clear that American-born, Dublin-based Tana French is the most interesting, most important crime novelist to emerge in the past 10 years,” proclaims Patrick Anderson (Washington Post). “Now, with the publication of her sixth novel… it’s time to recognize that French’s work renders absurd the lingering distinction between genre and literary fiction—the notion that although crime novels might be better plotted and more readable, only literary fiction, supposedly blessed with superior writing, characterizations and intellectual firepower, deserves the respect of serious readers.”

Laura Miller (The New Yorker) agrees, pointing out ways in which French’s books transcend the crime genre:

Yet, however convincing and well observed French’s Ireland feels, it isn’t the kernel of her work’s appeal, the thing that makes the Dublin Murder Squad series the object of an intense, even cultic fascination. French’s readers like to go online and rank the books (six so far, counting The Trespasser) in order of preference, and while there’s no consensus, it’s taken for granted that anybody who’s read one will very shortly have read them all. …Most crime fiction is diverting; French’s is consuming. A bit of the spell it casts can be attributed to the genre’s usual devices—the tempting conundrum, the red herrings, the slices of low and high life—but French is also hunting bigger game. In her books, the search for the killer becomes entangled with a search for self. In most crime fiction, the central mystery is: Who is the murderer? In French’s novels, it’s: Who is the detective?

Michael Helm, After James

Canadian author Helm’s new dystopian novel combines three overlapping novellas from three perspectives, and evokes “creepy” urban legends.

Cory James (The Literary Review) calls After James “dense, fascinating, and genre-defying,” adding, “Through its own unique grasp of narrative slithers and bends, After James masterfully places readers in the same predicament it has placed its characters. It not only raises profound questions about the nature of life and imagination in the modern world, but actually dares to answer them.”

Emily Smith (Ploughshares) is also a fan:

Part ghost story and part detective novel, After James by Michael Helm is a novel of ideas descended from creepy pasta, or urban legends from the Internet.

It’s not that After James terrifies the reader the way a horror movie might, but that the reader’s own suspicion of each character is unsettling, as if when a page is turned the characters shuffle and test your attention. As if when you close the book, they curl their fingers off the page and rearrange words you remember in a different order.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.