Five Books Making News This Week: Debuts, Icons, and Poets

Jung Yun, Claire Harman, Brian Blanchfield, and More

Ten emerging playwrights, poets, writers of fiction and nonfiction—win $50,000 Whiting Awards this week. Among them, J.D. Daniels and Catherine Lacey, who have books due out in 2017, Ocean Vuong and Safiya Sinclair, who are publishing new collections later this year, and Brian Blanchfield, whose essay collection is just out. A first novel explores the impact of the housing crisis and violent crime on a young Korean-American father and his family, a new biography of Charlotte Brontë celebrates her bicentennial, Adam Hochschild’s look at the Spanish Civil War underscores the contributions of American volunteers, and a Joseph Brodsky memoir written in English is a best seller after being translated into Russian—but it has yet to find a publisher here.

Brian Blanchfield, Proxies: Essays Near Knowing

Blanchfield’s Whiting award is announced on the eve of the launch of his essay collection, giving this poet a rare conjunction of good fortune and good timing. Early reviewers are impressed, as are the Whiting judges: “The quiet but searing vulnerability in Brian Blanchfield’s writing is as wide and trembling as the wingspan of his otherness. He writes with a beguiling sagaciousness that made me bow my head so many times that I lost count. These are essays about honesty and the revelation of self in which shame and guilt are dissected and anything extraneous scrubbed away. Each sentence is a live wire. Diverse, maybe mismatched styles, genres and topics accrue to great and moving effect, a profound whole made from an unlikely assemblage of parts. He appears to be forging a new genre before your very eyes.”

Publishers’ Weekly gives Proxies a starred review: “The themes of secrets and concealment pervade the collection…with its catch-and-release rhythm—sometimes lyrical, sometimes barbed. The concluding essay ‘Correction,’ which fills in or corrects details for the other selections, offers its own tribute to the processes by which we construct meaning—the real subject of this elegant and astonishing book.”

Ander Monson (BOMB) notes that Blanchfield’s “decision to work from memory gives these essays a contingent feel.”

These are high-wire acts that are a ton of fun to read. Here’s what I think I know, they say; watch me try to make something of it. And they know very many things indeed. A few of the subjects covered include housesitting, plastic surgery, tumbleweed, shame, abandonment, Man Roulette, footwashing, proprioception, frottage, and dossiers. This last piece, one of the best in the book, appeared in BOMB, and should give you a good sense of the intellect that Blanchfield brings to bear in each essay. It’s a deft one, performing close readings of cultural phenomena and tracking—with great, even heroic care—minor and major emotional transactions and tendencies. The result is a book of dynamic, thoughtful, and flat-out moving essays. These proxies are short but extremely sticky. They stuck with me. I’m carrying them with me as I write this sentence. I think you’re going to want to get sticky too.

Jung Yun, Shelter

Kyung Cho is headed toward tenure, but mired in credit card debt; he and his wife Gillian, the daughter of a policeman, and their young son are further at risk when he learns their house is “under water.” Then his mother, who lives nearby, is the victim of a violent break-in. Yun transforms the stuff of headlines into a gripping first novel.

“Yun’s debut may be a family drama, but it has all the tension of a thriller, “ writes Steph Cha (Los Angeles Times). “It’s a sharp knife of a novel — powerful and damaging, and so structurally elegant that it slides right in.”

“Race politics weave throughout the novel — a white person with an ignorant comment here, the compulsory assimilation of Asian-Americans there — but the most interesting commentary on race and ethnicity lies in its critique of the American dream through the parallel stories of an unhinged family, the housing crisis and a random act of violence,” writes Rani Neutill (New York Times Book Review).

Kim Fu (The Rumpus) calls Shelter “a desperate howl from the half-generation between the straightforward, gendered culture clash of Jin’s generation and the progressive, gender-disrupting individuation of mine. The book’s gaze is fixed firmly backward, sons suffering for the sins of their fathers, tortured and hostile men begetting more of the same. There’s reason to hope this is becoming yesterday’s story, and the world is ready for something new.”

Claire Harman, Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart

Timed to be published on the bicentennial of her birth, Harman’s new biography of Charlotte Bronte emphasizes the radical originality of her imagination—Jane Eyre was the first novel in the first-person voice of a child–and the ways in which her work was fueled by her sense of her society’s injustices toward women and children. Harman, biographer of Sylvia Townsend Warner, Fanny Burney and Robert Louis Stevenson, gets high marks for solid work.

When Jane Eyre was published in 1847, writes Laurie Stone (Denver Post), “it was an immediate rage. The intimate voice of the storyteller made people feel as though she was speaking directly to them.”

Charlotte looks out, speaking for everyone ever sold short. She speaks for the right of women, plain or beautiful, to claim love. She has found an affectionate champion in British biographer Claire Harman, whose lively and exhaustively researched Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart arrives on the 200th anniversary of Charlotte’s birth.

Do we need another Bronte bio, given the dozen or so captivating meditations that have followed Elizabeth Gaskell’s brilliant and gossipy pioneer study, published in 1857? Of course we do. Harman’s story is about how writers write.

Julia M. Klein (Los Angeles Times) notes that Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography lionized Bronte two years after her 1855 death. It had the “virtue of immediacy,” she writes, “but suppressed details of Charlotte’s unrequited love for her married Belgian schoolmaster. Later biographies, including Lyndall Gordon’s Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life (1994), rectified the omission. Claire Harman puts the frustrated romance at the center of Charlotte Brontë: A Fiery Heart, depicting it as the key to Brontë’s psyche and her work.”

“Harman’s well-paced narrative and keen attention to the tentative and troubled way Charlotte adjusted to sudden fame make this latest version of a literary life all the more modern and captivating,” concludes Carl Rollyson (San Francisco Chronicle).

Elizabeth Toohey (Christian Science Monitor) calls Harman’s biography “an irresistible read even for those familiar with her story.”

“Harman’s tart, understated wit and gift for quotation shine throughout,” writes Katherine A. Powers (Chicago Tribune). “She is also generous with incident and telling details, among them Charlotte’s unsuccessful attempt at improving her appearance with a hairpiece (‘a wad of brown merino wool’) and her high-handedness with an unmarried friend once she herself had become a wife. Who can say at this point which is the best biography of Charlotte Brontë, but Harman’s is among them and perhaps the most engaging of all.”

“This biography is careful, well-judged, nicely written — perfect if you’ve never read a biography of Charlotte Brontë published after 1857, not quite necessary if you have,” concludes Deborah Fredell (New York Times Book Review).

Adam Hochschild, Spain in Our Hearts

The Spanish Civil War was covered by some of the major literary figures of the time, and hundreds of reporters. Hochschild’s research on the lesser known Lincoln Brigade and other volunteers brings untold stories to the fore.

“Orwell and Hemingway come alive in this volume,” writes Dwight Garner (New York Times). “So do the two New York Times reporters, Herbert L. Matthews and William P. Carney, who reported from — and, Mr. Hochschild suggests, sympathized with — opposite sides (Mr. Matthews, the Republic, and Mr. Carney, Franco).”

But, he adds, “The best stories in Spain in Our Hearts tend to be the smaller ones, which the author patiently teases out. We follow a Swarthmore College senior who becomes the first American casualty in the battle for Madrid, for example, and a 19-year-old woman from Kentucky who heads for Spain while on her honeymoon.”

Bob Drogin (Los Angeles Times) writes, “The tragic story of the Americans in the doomed Lincoln Brigade — who bore some of the toughest fighting and heaviest casualties of any unit — comes vividly to life in Adam Hochschild’s compelling Spain in Our Hearts, a long-overdue book that explores this long-overlooked conflict. Hochschild cautions he hasn’t written a history of the war or even of the Lincoln Brigade. He instead focuses on a handful of Americans to tell the larger story of why Spain loomed so large at the time. Mining letters, unpublished memoirs and other archives, Hochschild recounts how Americans like Bob and Marion Merriman, graduate students from Berkeley, were drawn to what they considered a utopian society and what they rightly saw as the opening round in a global battle against fascism.”

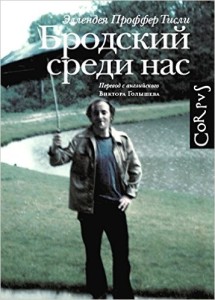

Ellendea Proffer Teasley, Brodskij sredi nas (Brodsky Among Us), translated from the English by Viktor Golyshev

A book written in English is a sensation after being translated into Russian. Here’s why American publishers should care.

Cynthia Haven (The Nation) calls the short memoir “an iconoclastic and spellbinding portrait, some of it revelatory.”

Teasley’s Brodsky is both darker and brighter than the one we thought we knew, and he is the stronger for it, as a poet and a person. The book’s reception itself is instructive. Since its publication by Corpus Books in the spring of 2015, Brodsky Among Us has been a sensation in the poet’s former country, quickly becoming a best seller that is now in its sixth printing. Last spring, Teasley made a triumphant publishing tour, speaking at standing-room-only events in Moscow and St. Petersburg; Tbilisi, Georgia; and a number of other cities. The book received hundreds of reviews. According to the leading critic Anna Narinskaya, writing in the newspaper Kommersant, Teasley’s memoir had been written “without teary-eyed ecstasy or vicious vengefulness, without petty settling of scores with the deceased—or the living—and at the same time demonstrating complete comprehension of the caliber and extreme singularity of her ‘hero.’” Galina Yuzevofich, in the online publication Meduza, praised Teasley’s “exactness of eye and absolute honesty,” resulting in a portrait of “wisdom, calm, and amazing equanimity.” Even so, the book has yet to find a publisher in English, the language in which it was written.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.