Five Books Making News This Week

Katrina, the Fall of Saigon, Opium Wars, Maine

A decade ago, on August 23, 2005, the devastating storm known as Hurricane Katrina commenced a trail of damage that changed the landscape and led to immeasurable human tragedy. Dozens of new books mark the tenth anniversary of the storm, including two below. Also on the critical radar this week: new Maine stories from Ann Beattie, the last in Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis triology, and a noir novel haunted by the fall of Saigon.

Katrina: After the Flood, Gary Rivlin

Susan Larson (the New Orleans Advocate) calls Rivlin’s report on what happened during the storm, the bureaucratic snarls and blockages afterward, and the human cost to all, “one of the must-reads of this season” in her list of a dozen new Katrina-themed books. “Some amazing New Orleanians populate these pages,” she writes, “including Alden McDonald. of Liberty Bank; the Wall sisters — Cassandra, Petey, Robyn, Tangee — of New Orleans East; Mack McLendon, of the Lower 9th Ward Village; Pam Dashiell, of Holy Cross; developer Joe Canizaro; Boysie Bollinger, of Bollinger Shipyards; Sally Forman, then of the Nagin administration; and Ron Forman, the Audubon Institute, and most of the politicians of the past 10 years, including former Mayor C. Ray Nagin and present Mayor Mitch Landrieu.”

“Rivlin is a sharp observer and a dogged reporter,” notes Nathanial Rich (New York Times Book Review) in his evaluation of Rivlin’s book, which is “among the first to relate, in clear and scrupulous detail, the decisions that have brought us this far, and to identify those who made them.” Rivlin, he adds, is “unerringly compassionate toward his subjects — even Nagin, who recently began serving a 10-year sentence for corruption at a federal prison in Texas. But Rivlin’s most valuable journalistic skill is his acute sensitivity to absurdity. He is particularly piqued by the absurdities of racial and economic injustice. He examines the specter of a ‘Katrina cleansing’ — fears that the city’s business elite were conspiring to repossess property and re-establish a white majority electorate. Lance Hill, a white political activist serving as a mole, tells Rivlin: ‘It was impossible not to pick up on this sentiment that this was our chance to take back control of the city. There was virtually a near consensus among whites that authorities should not do anything to make it easy for poor African-Americans to come back.’”

Sea Lovers, Valerie Martin

In her review of the “complex and wonderful” stories in Martin’s career-spanning collection, Sylvia Brownrigg (The New York Times Book Review) highlights the stories set in New Orleans, “where the inescapable heat encourages fevered anxieties and can melt reality into unfamiliar shapes.” The city, she writes, “comes to life in Martin’s hands. She gives us an exotic as well as historic Louisiana in the story about the centaur (which includes a great scene where the creature is moved to tears by a Donizetti opera), but she doesn’t overlook the city’s poverty, its shallow tourist attractions and, of course, its daunting climate. ‘The heat,’ the narrator of ‘Beethoven’ confesses, ‘freighted with turpentine fumes, assaulted me, as fierce as a roomful of tigers.’”

The State We’re In, Ann Beattie

The State We’re In “is a work of double meanings,” writes the Los Angeles Times’ David Ulin, “beginning with that title: The 15 stories here take place in Maine, where the author spends part of each year, but it is also a reference to a more existential state.” His analysis continues:

Moving fluidly between adolescents and septuagenarians, it leaves us with the sense that uncertainty, disconnection, is not a matter of chronology but rather of being alive. As Beattie explains in “Duff’s Done Enough”: “The whole world’s full of stories. I never doubted that. Every writer will tell you the same thing: It’s next to impossible to find the inevitable story, because so many needles appear in so many haystacks.”

Think, then, of The State We’re In as 15 needles, 15 slices of life. Some are sharper, more pointed, than others, but all share a sense that meaning, or engagement, remains slightly out of reach.

“Splendid,” concludes Howard Norman (The Washington Post). “This collection has many, many moments of utter surprise. In fact, every page is fitted out with the blessed finery of hypnotic storytelling.”

Nicole Jones (Vanity Fair) dubs The State We’re In “a peerless, contemplative page-turner.”

Beattie has “created characters and situations that are edgy, funny and dark,” writes Carol Memmott (Minneapolis Star-Tribune).

Ellen Kanner (Miami Herald) concludes Beattie’s “trademark sleek prose and perfectly calibrated authorial distance, [make]for weirdly entertaining reading. Only Beattie can see an upended Adirondack chair as giving “the finger to the very symbol of summer.”

Flood of Fire, Amitav Ghosh

The last in the Ibis trilogy (after Sea of Poppies, which focused on the 1838 voyage of the British schooner Ibis, and River of Smoke, which described the aftermath of a violent storm) strikes Wendy Smith (the Los Angeles Times) as “sprawling” and “stirring.” Flood of Fire, which focuses on China’s attempts to end the opium trade imposed by the British East India Company, leading to the first Opium War, ends “after the skies and gunpowder haze have cleared, in June 1841, the war still has 15 months to go, and the Ibis is bound for parts unknown with several key figures on board,” Smith writes. Ghosh has chosen “to stop rather than wrap up his trilogy, leaving in transition many people to whom we have grown attached over the course of three novels. It’s a mark of his artistry that this ending, though in some ways inconclusive, nonetheless feels satisfying and right.”

Ann Klefstad (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) describes Flood of Fire as “riveting,” “dashing, tragicomic,” a “propulsive drama,” adding, “Opium, gold, sex, blood and seawater create an elixir that still shapes the world.”

Katherine A. Powers finds Flood of Fire the best of the trilogy: “It adds colorful threads to the plot, weaving them into the existing story and tying them off in a most satisfactory way. Further, the novel provides highly dramatic depictions of key land and sea battles of the First Opium War. Beyond that, it presents a savvy account of the influence of the opium lobby on British foreign policy and the mental contortions of the ‘Apostles of Liberty’ who identified the diabolical trade, so destructive of the people of both India and China, with freedom, commercial righteousness and religious enlightenment — all virtuously bestowed with guns and gunboats.”

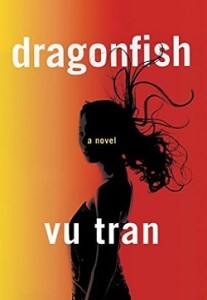

Vu Tran, Dragonfish

Gerald Bartell (San Francisco Chronicle) defines Dragonfish as “pure noir,” with its tough-talking narrator Robert Ruen, a 20-year veteran of the Oakland police force, at the end of a “torturous” relationship with Suzy, a Vietnamese woman “whose “violent nature” matches his own. The letters Suzy writes to her daughter about their harrowing nine-day sea journey after the fall of Saigon and their time in a Malaysian refugee camp, Bartell writes, are “simple yet rich in their images and philosophical musings.” Eventually, he adds, “her absorbing narrative melds beautifully with the book’s main story and its surreal visions of Las Vegas, a terminus for these displaced Vietnamese refugees and their dreams: ‘Here,’ Suzy writes, ‘the world outside always feels awake and alive with the stories it desperately wants to tell you. … Nothing here to remind you that the lights will one day go out, that all stories end whether you want them to or not.’”

NPR’s Maureen Corrigan calls Vu Tran’s Dragonfish a “superb debut novel” that “takes the noir basics and infuses them with the bitters of loss and isolation peculiar to the refugee and immigrant tale.” Corrigan compares the work favorably to earlier noir classics:

Noir has always been a nightmare genre about displacement, about people and things fated to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Some of the greatest noir film directors like Billy Wilder and Fritz Lang were themselves refugees, in their case, fleeing from Hitler’s Germany. In Dragonfish, Vu Tran has given us a haunting literary noir about a newer regeneration of refugees and immigrants who find themselves lost in America.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.