Five Books About the Most Important Photographs of the Vietnam War—and the Photographers Who Took Them

An Essential Reading List from Gary Knight

In April 2023, George Black wrote in an introduction to his reading list on these pages that “something like thirty thousand books have been written about ‘the Vietnam War.’”He limited his reading list to the American War, not the French. I am limiting myself further, to five books that are an essential entrée for anyone who wants to understand how the war was photographed and by whom.

The list might provide context to a critically acclaimed documentary film directed by Bao Nguyen called The Stringer, released on Netflix in November. In the film, a former photo editor at the Associated Press Saigon bureau reveals a secret he’s been haunted by for 52 years, setting off a gripping two-year investigation into the truth behind perhaps the Vietnam War’s most iconic photograph. Central to the film’s narrative, a small team of journalists from the VII Foundation, of which I am one, embark on a search to locate and seek justice for a man known only as “the stringer.” The film addresses themes of injustice, accountability in journalism, the mutability of truth, who gets to frame the narrative, and who gets erased.

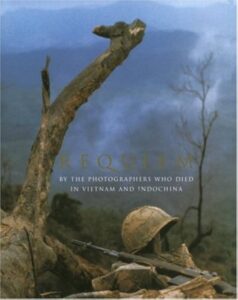

What’s hard to find among the 30,000 books written about the wars in Vietnam are Vietnamese perspectives, and in the books that illuminate the photography and journalism of those wars the presence of the Vietnamese is even harder to find. The war may have been a high-water mark of journalism, but the channel was narrow. Denise Chong’s The Girl in the Picture about Phan Thi Kim Phúc is a notable exception, examining the life of a young Vietnamese girl who became one of the most prominent child victims of war because she was photographed burning alive. Unlike most subjects of war photography she took ownership of the photograph that victimized her and turned it into a weapon for peace. Vietnamese perspectives appear on the poignant pages of Requiem, curated by German and a British photographers Faas and Tim Page–but to make it onto those pages you had to have been killed. Here then is a list that asks whose perspectives are missing, as much as it points you towards those that deserve attention.

*

Denise Chong, The Girl in the Picture

Chong’s biography is a deeply researched and empathetic biography of Phan Thi Kim Phúc—the child captured in the famous 1972 “Napalm Girl” photograph, which is the subject of the Netflix documentary The Stringer. The book traces her life far beyond the instant that made her an icon of the Vietnam War. Chong tells Kim Phúc’s story from her childhood in the village of Trảng Bàng, through the horrific napalm attack that left her severely burned, to her long and painful recovery in Vietnamese hospitals.

A significant strength of the book is that it restores Kim Phúc’s full humanity. Portraying her as a victim is unavoidable, but Chong develops Phúc’s personality as a thoughtful, resilient young woman navigating the pressures of being used as a political instrument by the Vietnamese government, the weight of global fame she never asked for, and the private battle of rebuilding a life shaped by severe trauma. Chong also contextualises Kim Phúc’s story within the broader history of the war and postwar Vietnam, giving readers a clear view of how ordinary families were caught in geopolitical forces beyond their control and unimaginable to them.

The narrative follows Kim Phúc into adulthood—her education, religious awakening, defection to Canada, and, by taking ownership of the photograph in which she was unwillingly portrayed, her eventual emergence as a humanitarian advocate for child victims of conflict. Researched and written in the 1990s, Chong writes with clarity and compassion, grounding the book in interviews, archives, and close access to Kim Phúc and her family who are now living in Canada. Of the three million Vietnamese casualties between 1955 and 1975, approximately two million were civilians. This is one of the few books that has been written about their experience.

Philip Jones Griffiths, Vietnam Inc

Philip Jones Griffiths’ Vietnam Inc. remains one of the most searing and enduring photographic indictments of the American War in Vietnam, and of any war. The book blends reportage, moral inquiry, and political analysis in a way that still feels unsettlingly contemporary fifty-four years after it was published. Griffiths wasn’t chasing battlefield heroics; he was documenting the human cost of the war on civilians and soldiers, and exposing the contradictions within U.S. policy and the moral dissonance of a technologically superior army fighting a largely rural population. The result is a body of work that cuts through propaganda and forces the reader to confront the war’s lived reality.

What makes the book so powerful is Griffiths’ deliberate, patient approach. His photos are intimate, often quiet, and always respectful of the people he photographs. Griffiths, a Welsh nationalist, identified with the Vietnamese and, instead of framing them as abstractions or victims, he gives them individuality and dignity. That stands in stark contrast to the dehumanizing language common in Western reporting, particularly photojournalism at the time. His images of dislocation, erasure, chemical defoliation, and the militarization of daily life are paired with analytical and empathetic commentary.

The book is not just anti-war; it’s an investigation of power, culture, and the ways ordinary people adapt to extraordinary circumstances. Griffiths exposes the contradictions within U.S. policy and the moral dissonance of a technologically superior army fighting a rural population.

Half a century later, Vietnam Inc. remains a benchmark for conflict photography. It is an example of how political and moral clarity in visual journalism can challenge official narratives, shape public opinion, and hold institutions accountable.

Michael Herr, Dispatches

Michael Herr’s Dispatches is a fast-paced, hallucinatory account of his time covering the American War in Vietnam War for Esquire, built from vivid, ground-level experiences that show the psychological chaos of the conflict. Herr doesn’t pretend to be objective or detached; he admits how the war pulled him in and seduced him, which is why the book remains one of the most influential pieces of war writing.

The book’s power comes from its honesty about confusion, fear, adrenaline, dark humour, and the psychological strain of the conflict. Herr doesn’t pretend to be detached. He acknowledges how the war clawed at him emotionally and mentally, and how difficult it was to make sense of anything in a place where meaning was always slipping. That subjective style—intense, impressionistic, and brutally candid—makes Dispatches one of the most influential pieces of war reportage ever written. Dispatches is essential to understanding a cluster of journalists who covered the war, notably the enigmatic hippies and stoners in the circle around whom photojournalists Tim Page, Dana Stone and Sean Flynn were the centre of gravity. Three combat photographers who embody the extreme freedom and danger whose real lives are encapsulated in Denis Hopper’s fictional character in Herr’s screenplay for Apocalypse Now.

Herr’s portraits of Page and Flynn aren’t side notes; they explore a sub-sect of Vietnam-era journalism, far removed from the ivy leaguers and wire-service reporters. Embedded in the same madness, fear, and confusion as the soldiers they covered, Page, Stone and Flynn were improvisational, unsupervised, and driven by a desire to participate.

Elizabeth Becker, You Don’t Belong Here

Elizabeth Becker’s You Don’t Belong Here is both a reclamation and a correction. It is an account of the Vietnam War told through the lives of three women who broke into a profession that insisted they had no place in it. Becker profiles photojournalist Catherine Leroy, and reporters Frances FitzGerald and Kate Webb, each defying the rigid gender expectations of the 1960s to report one of the most devastating conflicts of the century with a clarity and toughness that reshaped war journalism, challenging the clichés and distortions that dominated Western coverage.

Becker writes about her friends with moral authority and empathy. She grounds the women’s achievements in the brutal realities they faced: institutional sexism, condescension from male colleagues, and the physical danger of covering a war that swallowed journalists whole.

Becker celebrates her subjects without mythologising them, and she frames their work within the larger failures of the era’s reporting.

You Don’t Belong Here ultimately argues that these women didn’t just earn a place in Vietnam—they changed what journalism could be. Leroy was the only photographer to parachute into combat in Vietnam, her raw and elegant frontline photography, FitzGerald’s educated and sweeping political analysis, and Webb’s unflinching dispatches reveal not just three diverse and individual talents, but three distinct ways of seeing, each of them pushing past the male-centric narratives that defined the war and created space for future generations of women war journalists.

Horst Faas and Tim Page, Requiem

Requiem is a book built from absence, the 135 photographers who died covering the wars in Indochina. Horst Faas and Tim Page gather fragments: a handful of pictures, a short biography, and the final coordinates of their lives. What emerges is not a history of the conflict but an accounting of Vietnamese and foreign (mostly Western and Japanese) photojournalists who went to war and never came home.

Requiem’s signature achievement is its multinational perspective, placing Vietnamese and foreign photographers on equal memorial footing. The contrast between the Vietnamese who humped through rice paddies documenting their own country’s existentialist struggle, and the foreigners who flew around on helicopters and were given US military ranks adds emotional depth and historical nuance.

Faas and Page were Western correspondents who, in very different ways, were deeply embedded and represented very different poles of the foreign press corps. The book’s tone, though empathetic, still bears traces of that viewpoint – e.g., emotional emphasis on Western losses and camaraderie. Some readers might wish for more Vietnamese narrative framing or commentary. The result is a memorial that aches with what’s missing as much as with what’s preserved. Vietnamese photographers working for North Vietnamese, South Vietnamese, and local news agencies often operated with fewer resources, under stricter political controls, and in conditions where the war was also their home.

Foreign photographers, especially from the U.S., Europe, and Japan, typically had better equipment, press access, and the ability to withdraw from the conflict. Their work often centres on dramatic frontline action or the moral confusion of an outsider witnessing another nation’s suffering. Many were driven by professional ambition, idealism, or shock at the brutality they encountered; several died venturing into combat zones with a mixture of courage and naiveté.

The book is a powerful tribute, illuminating how differently the same war was experienced by those who lived it and by those who came from outside to witness it.

Gary Knight

As an aspiring young photojournalist in South East Asia in the 1980’s, Gary Knight (b. 1964, UK) supplemented his meager picture sales by selling his own blood. In the Balkans, he developed his career working on the frontlines in that violent civil war, where he met lifelong friends Alexandra Boulat, Ron Haviv, Christopher Morris, and James Nachtwey, who, with Antonin Kratochvil and John Stanmeyer all became founding members of VII Photo Agency. Crisscrossing the globe for Newsweek and building networks everywhere, he saw the demise of the traditional photo agency model and the early signs of decline in print media. His determination and vision led to the creation of VII. As Executive Director of The VII Foundation, he leads a team that supports fiercely independent journalism and trains and mentors a new generation of journalists in the Majority World, who are best placed to tell their communities’ stories to the world.