Nine-thirty in the morning on a cold, bright Saturday. Asase, Rumer and me huddle at the bus stop near Dub Steppaz, waiting for the 207 into London. The record shop is one of our few places of refuge in dis yah town. Riddim is the foundation for all of them: dance hall; Pentecostal church where people sway and stomp, waiting for the white smoke of the Holy Ghost to enter their bodies; and Dub Steppaz, a fortress of black vinyl.

All of them governed by men.

I like to go to Dub Steppaz on my way home from the night shift, eight in the morning when the shop has the CLOSED sign in the window, before it’s full of men jostling for dubplates in the small-island oasis. The walls plastered with glossy vinyl sleeves of Caribbean beaches and rainforests, musical revolutionaries in Kente print robes, their dreadlocks trailing into the earth, becoming the roots of trees. The ceiling painted with hummingbirds.

Eustace lets me in and locks the door, gives me a mug of coffee while he wipes down the counters and polishes the vinyl, a rare-groove track playing, something about silver shadows.

Eustace is a square-jawed man in his early forties; not exactly old, but with enough experience and wisdom to keep the youth on solid ground. Mothers and grandmothers drop in on their way from the market to get advice from him about a son or grandson running wild.

Asase loves nothing better than pushing herself into the crowded record shop late on Saturday afternoons when we return from the city. By that time it’s ram-up with men, their arses pressed against the window, criss-crossing smoke above them. Rumer always tries to drag her past the shop, but it’s pointless. Asase opens the door and eases herself in and – yeah, we follow.

She’ll work her way to the back of the room where the records are stacked in tiered wooden cabinets. Me and Rumer go to the far side and pile our bags on the narrow counter that’s littered with empty cans of beer. The place smells of body odour, stale rum and roll-up tobacco.

Asase likes to flick slowly through the vinyl, undulating her spine to the music as if it’s a divining rod and she’s seeking the water’s flow. She sucks up the attention as men sidle up to her, asking ‘What’s up, baby-love?’ If it gets too ram and rude bwoys get agitated, Eustace will raise the counter and let us stand with him.

Now I knock on the shop window and wave to Eustace. He waves back and then returns to sorting vinyl.

We board the half-empty bus for the hour-long ride into London, still dub-travelling on the undertow of ghostly basslines from the Crypt where we were dancing with Moose until dawn. He picked us up from Asase’s place like he has done more or less every weekend since that first night a few weeks ago.

We’ve done danced Friday into the stratosphere, skanking as if our lives depended on it, scooping the air with our hands, back-kicking like we were treading water. We grabbed a fresh – a cat-wash and change of clothes – at Asase’s yard. Mopped up stewed fish with breadfruit, dozed, smoked ourselves awake – or kinda. From rave to street, no sleep. That’s the way we run it half the time.

I stare out the window, feeling Asase’s weight shift into me as the bus turns.

Sometimes Asase goes home with a man after a blues party to get her tings. Other times, I spend the night with her, waking up Sunday afternoon, dozing on the maroon velvet sofa in the back room of her yard, watching black-and-white films with the curtains drawn while Oraca’s in the kitchen. Oraca cooks nuth’n but fish: stewed, fried, boiled, but mostly stuffed with herbs. The house always smells of fish and the sea.

After dinner, when we’re half-crazed from the fallout of ganja high and sound-system nosebleeds, Oraca lights candles and puts a jazz record on, the volume humming on the low-down like a distant sea.

We get on the floor, eat escovitch red snapper from big glass bowls, push our plates away and lie on our sides, Asase on Oraca’s right, me on her left, and Oraca telling us about Queen Nanny of Jamaica, a Maroon leader. She tells us this with sound hissing through the tunnels of her clenched teeth.

‘People call them runaway slaves. No! They fought the British and won. Nobody could put Queen Nanny and her warriors under manners. She was a supernatural leader. Her tactic was sound – long-range communication, the abeng horn.’

Maybe the way Muma sings to me is the same. She’s transmitting memories. Like dub and reggae, communicating our history.

In London, Asase, Rumer and me float down side streets of boutiques starlit for Christmas, wading through the light, trailing smoke. Yes, iyah! We’re high. Puss-eyed sunshades on, cooling our bodies in the glass-city.

We push through the swelling morning crowds of crutchers, shoppers, boasty in pavement bars pecking breakfast food like they don’t know how to nyaam.

‘I’m mash-up,’ Rumer says. She rummages in her green-beaded clutch bag, finds her inhaler, sucks in whatever magic is in the blue tube.

‘Gimme some a dat,’ Asase says. She grabs it, breathes in. Coughs. ‘Yuh crazy raas,’ Rumer says.

‘Stuff’s good,’ Asase says. ‘Let’s tek the city. Shop by shop till we drop.’

Rumer leans on Asase, holds her arm, eases her right foot out of her gold-tipped shoe. Stubby toes swollen and grey as slugs. She looks up at Asase and says, ‘My feet are sore.’ And there’s that strange look in her eyes that she gets sometimes when she’s close to Asase. Red flushing her face like she’s blooming and bleeding at the same time.

‘You’re saaaft. Twisting up yuh foot wid skanking,’ Asase says.

She pulls away and marches ahead.

Street vendors toss peanuts in spinning copper plates that hum caramel notes like the flipside of a 45.

Tuuune in.

Tuune in till a morning.

People stare at us. We don’t dress pop. We spin our garments different, wear our music on our bodies. Whipcrack pleats, spliced textures, rewind old-time swing skirts, turned-up bling.

I look at Asase. What-a-way she brucks style. There’s Rumer in her men’s grey Farah trousers and suede waistcoat, and me in my stitched-seam jeans, gold-tipped patent shoes. But Asase? My girl has customised a pair of cream high heels with diamond-encrusted toecaps – Stix-Gyal style – matched with an A-line georgette skirt, big-arse ducket on a rope chain doubled around her throat.

She stops and eyes a sashay dress with transparent bodice and rainbow pleats through a shop window. Bad’n’raas stylish. Cut to kill.

‘That garment’s gonna be the price of a second-hand Spitfire,’ Rumer says. ‘Probably get you inna jus’ as much trouble.’

‘Watchyah, nuh!’ Asase says.

She presses the buzzer. Waits. Rings again. Two saleswomen, folding shirts, look up, assess and dismiss us with rigor mortis smiles. A blonde with fire-bombed rouged cheeks looks at the clock on the wall and shakes her head.

Asase takes out her snakeskin purse, holds it up and points to the outfit. Mouths, ‘Five minutes,’ filling the narrow doorway with her broad-shouldered stance.

They buzz us in. The blonde woman folds the dress and wraps it in bright pink tissue paper.

‘I want a top-notch carrier bag for my garment, nothing plastic,’ Asase says to the assistant as she writes a cheque.

I look at the signatory’s name printed on the chequebook: Lucy Blewitt. I wonder who the hell this Lucy is, and I can’t believe that Asase is hustling again.

Me and Rumer work nights at Bonemedica on the production line, operating machines and inspecting components – bolts and screws that fix the broken parts of people’s bodies. A sprawling grey-brick building in the industrial area south of the railway, full of factories making canned meat, bread, pottery. We sleep in the daytime, come alive at night.

Asase works part-time for a company in the city that makes perfumes. Dressed in silk wrap dresses, sniffing and mixing. ‘Like mekking music,’ she says. ‘Every scent’s a note.’

She doesn’t need to hustle. She earns enough to rent her own flat, but she’s saving to buy a double-fronted house in the fancy town where she went to school. On her days off, she goes to the city with other crutchers, stealing clothes from designer shops, shoving them between their legs.

When me and Rumer are at Bonemedica in the dead of night with the other late-shift workers, Rumer’s like a ghost, her thin frame hunched over the desk, inspecting the parts and updating the maintenance logs, her pale freckled face covered in tan foundation. She’s quieter when it’s just the two of us, as if she needs Asase’s energy to fire her up. I wonder why she comes to the Crypt, the only white woman, getting bounced by Stix-Gyals, tuff’n’raas women like Asase, who hustle and fight to survive. They wanna know why she’s there, where she’s from. ‘You mixed or what?’ they ask her. ‘Irish,’ she’ll tell them.

Rumer’s family are Travellers. They move from town to town, country to country, in their caravans. She left them five years ago to get away from a man they wanted her to marry. The council gave her a studio flat.

Rumer’s like me, trying to find where she fits. If she believes in ghosts or spirits, she won’t say. When I try to talk to her about Muma or the things I hear, she tells me: ‘Girl, that’s just vibrations.’

The blonde shop assistant looks at the signature on the cheque-book and compares it with the chequecard. She stares at Asase and Asase smiles inna her face. Not a real smile, a hard-faced show of teeth. The woman puts the dress into a silver cardboard bag and hands it to Asase.

‘Sweet,’ Asase says, except her tone might as well be saying ‘Fuck you’.

Once we’re back on the street I ask Asase where she got the chequebook. She doesn’t answer.

‘You can do serious time for stolen chequebooks,’ I say. ‘Who gave it to you? Do you know what they could have done to that woman?’

I almost never raise my voice with Asase, but there’s been a sick feeling in my stomach since I watched her dance with Moose that night we first met, and a glow in my fists when I think of the risk she’s exposing us to.

A fat vein twitches on Asase’s temple.

‘Chip, if you don’t like it!’ She’s in my face, her eyes popping. Then she links arms with Rumer. ‘You won’t go soft on me,’ she says to her.

‘Gyal, you’re outta order,’ Rumer tells her. But she doesn’t resist; she always gives in to Asase’s touch.

What made Asase such a force? Maybe it’s her family being from Alligator Pond, a fishing village in a valley between the Santa Cruz and Don Figuerero Mountains. The first people to navigate the sea and set foot on the island over a thousand years ago. Or maybe she’s different because her father, Hezekiah, is a man who does what he wants and raised Asase to do the same. Like the time Asase’s mother, Oraca, realised she was sneaking out to the Crypt when she was only thirteen. Hezekiah said to leave her be; the sooner she learned how to handle men, the better. She learned how to handle men, for sure. And now that Hezekiah no longer lives with them, she back-chats him in ways that even Oraca never could.

Or maybe Asase is different because she didn’t go to the same run-down school as me and Rumer. Father Mullaney wrote a letter for Oraca and got Asase into a quality Catholic school.

Babylon school is where I learned not to do my thing. Redstone Secondary seems such a long time ago. Rumer came to my school when she was fifteen. We both left when we were sixteen. I used to sing in the choir. They were happy for us to entertain them in return for us receiving their stories of history. Teachers with bullwhip tongues, faster than the speed of sound, talking about their conquests, plagues and fires.

I learned plenty about their history, but I had to go to the library to educate myself. Read up on some of the things Oraca told me about the Black Atlantic, the abeng horn, the revolution of sound.

Asase went to a school fifteen miles away, in a sleepy town with a cricket green, hanging flower baskets, gardens with treehouses. She liked the uniform: a blue blazer with brass buttons, pleated skirt, and black tie with gold stripes that made her look like she was in the navy. She always carried on extra. I suspected she was trying to climb the ladder out of Norwood, seeking friends in higher places.

The lights in the shops go out. Asase and Rumer march ahead on the darkening streets. Best shut me mouth: the sistren need each other on the streets, in the dance hall. Together we are a three-pin plug, charging ourselves to dub riddim. Connecting through each other to the underground.

I look at their backs; they’re almost the same height. Rumer’s tall, slim body dressed like a Stix-Man, a hard-man-criminal, arms linked with Asase, slightly taller, who is sashaying her arse as if to tell me I can kiss it.

I think of the many nights I’ve spent in Asase’s bed. It was some time after Hezekiah ran off with that young woman, when Asase was sixteen, that she developed a night-time ritual of stripping naked, dropping her clothes and underwear in a pool around her ankles. The first time she did it, I looked at the web of her black pubic roots, then her face.

What the fuck was she carrying on with?

She was nothing like Oraca and everything like Hezekiah, the father she says her spirit can’t tek. Same flared huffing nostrils, cedar-coloured skin, and irises that flickered brown and green like shaken leaves.

She took her blue silk headwrap from under her pillow and covered her hair, all the time her eyes on me, her mouth set in a deep-cut line. I was wearing what I always wore, her oversized T-shirt with ‘Sweet Pussy!’ printed on the front. I pulled it down below my crotch.

She was supposed to light the ready-made spliff that was in the ashtray on the brass drinks trolley that she used as a bedside table. Then switch off the lamp, take a deep drag of ganja and pass it to me, like she always did. We would then blow smoke above our heads and watch it form ideas that we’d try to articulate before they dispersed into silver particles of sound. Then wake the following Sunday around lunchtime, our legs wrapped around each other, face to face, lips almost touching. We always woke that way, no matter how we set our bodies and intentions before we went to sleep.

Only that night she whispered, ‘Yuh best wash your feet.’ ‘What?’

Silence, then zinging in my ears, like I’d been boxed in the head.

She screamed at me, ‘Your feet! They’re dirty! You think you can just walk across the bare floor and get into my bed?’

I didn’t move for a few seconds. She was breathing hard. I went to the bathroom and washed my feet, although there was nothing to wash. The wooden floor was polished and spotless. Was she listening for the sound of running water? Would she want to inspect my heels? Poke her fingers between my toes? I walked across the floor and stepped on to the orange sheepskin rug and got into the bed. I turned my back on her and curled into a ball.

I feel the same stress now, watching her and Rumer walk away.

It always takes me time to realise someone’s hurting me. A few minutes, a day, a year. Twenty-four years. Four hundred years. But at some point there’s the familiar feeling as my blood picks up speed, tracks and traces some evolutionary chemical inside my gut.

Rage.

In front of me city loners appear as if they’ve bubbled up from underground streams. Steam winds out from basement bars. Shop lights are searchlights. Sirens blare in the distance. I think of our people who’ll be snatched from the streets, swallowed by Black Marias, where they’ll curl up like bass clefs. Making breath marks inside the hold of those vans, knowing they may never be seen again.

My heart thuds. I wait for the screech of police cars coming to pick us up because of Asase’s skank with the chequebook.

Them put death on our people, Muma moans. Sea spells, daughter, sea spells.

The sirens fade.

The light’s gone and Asase’s shadow looms behind her, a dark mass. I’m disconnected from her and Rumer, locked outta my feelings again, zoned out. But this is my entry into the chirring afterworld where Muma is singing. I see her in the winding smoke. Her tissue-twisted curls matted with seaweed. Her sparkling, salt-encrusted bones.

__________________________________

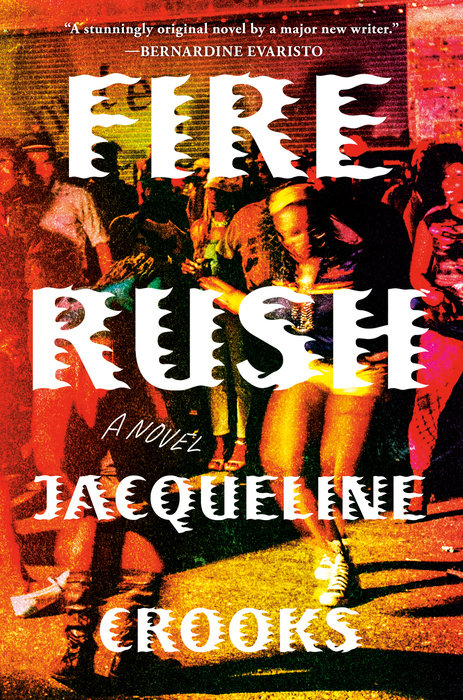

From Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks. Used with permission of the publisher, Viking. Copyright © 2023 by Jacqueline Crooks.