Finnegan’s Wake at 80:

In Defense of the Difficult

On the Pleasure of Annotating One of Literature's

Most Challenging Works

Finnegans Wake, published 80 years ago, is a difficult book. It’s a book so mired in misunderstanding that it makes its older, more famous brother, Ulysses, appear mainstream. It took James Joyce over 16 years to write, mired in the glow of his post-Ulysses fame and the gore of his personal life. But even 80 years on, it is “as modern as tomorrow afternoon and in appearance up to the minute.” In fact we may be just catching up to Finnegans Wake in many ways.

Finnegans Wake has always stirred people up. Composed of dozens of languages smelted together, the Wake must first be deciphered, then the often overlapping references spotted and the whole thing basically decoded to then enjoy the audible ripple of true fun running throughout. That’s not to say you can’t just open any page and start reading to experience its unique music. Joyce himself advised people if they were confused to simply read it aloud as it is often understood phonetically. And loads of people do. The fantastic project Waywords and Meansigns films people around the world reading the Wake aloud.

The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this?

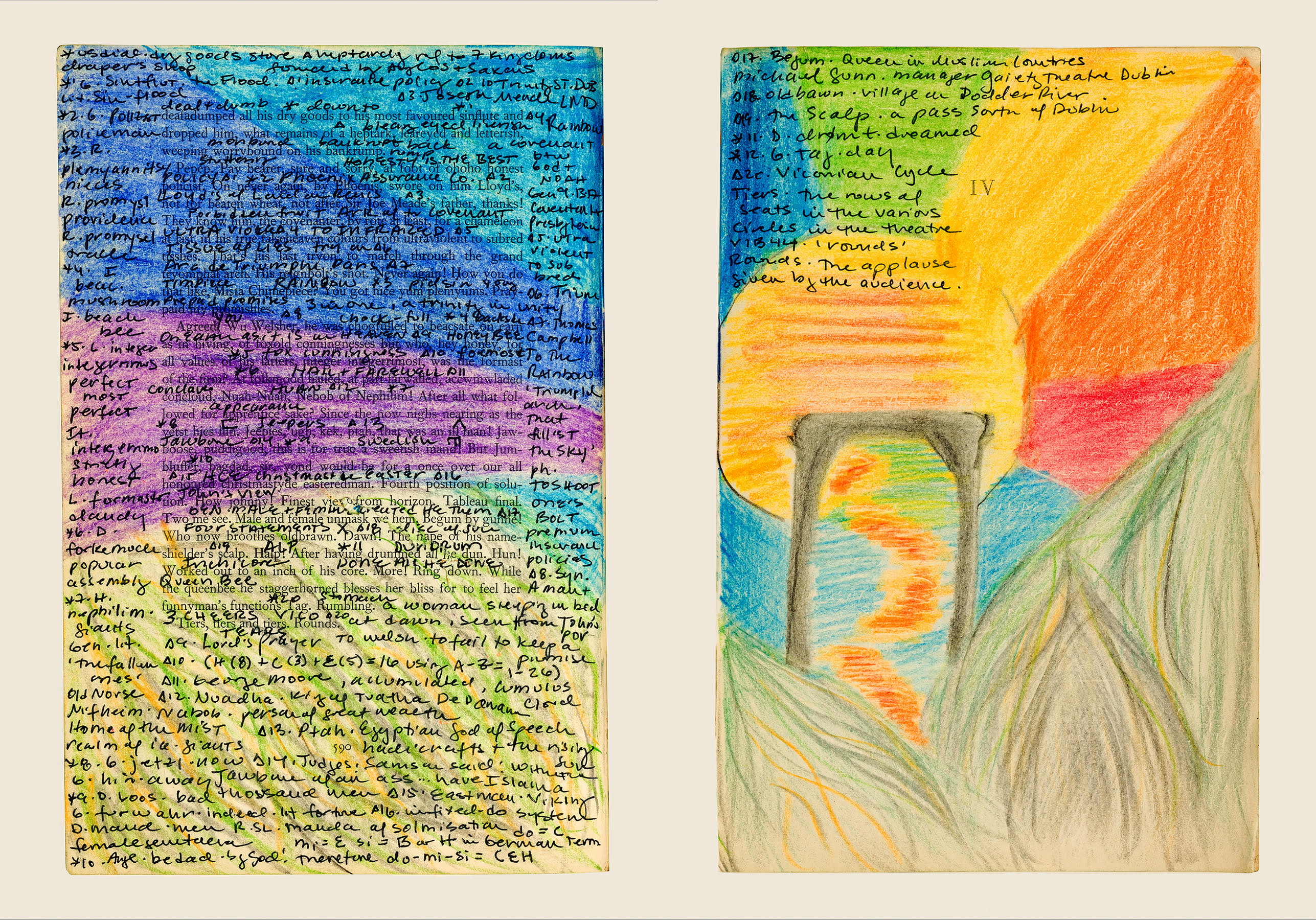

I was teaching yoga in public schools, losing a mother to Alzheimers, raising a child with severe issues and trying to Heimlich a long expired marriage. I was in such a deep depression it was difficult to see a way out. A friend asked me what I loved to do before teaching. I loved The Odyssey, art history, archaeology. I loved digging. They suggested I read Ulysses. I cringed. Persisting, I was shown the “water passage” from Ulysses and it quenched a thirst. My mind was instantly sucked into not only the text—hilarious, soulful, a true compendium of humanity—but the process leading to the text: annotation. The denser the better. By the time I got through Ulysses to the Wake I had hit upon what became a truly healing highlight of my daily routine. Just a page a day, as some would do a crossword, I read the Wake like an archaeologist; excavating line by line, writing down my finds in the margin and uncovering the most beautiful and complexly colored kaleidoscope which related to… really everything.

I first started drawing in my Wake to count the number of rivers mentioned in an episode, one page alone counting 85. Gradually, I would be so moved by a line or a character I would color them in, the most obvious being the 28 Rainbow girls to the more obscure nebulae, railroad tracks, hidden mythical islands and turn of the century lightships. Themes began to emerge which demanded documentation and always the sad, ecstatic relief of finishing a chapter merited some sort of colored tribute. By the time I finished four years later, I simply drew a leaf to reflect Joyce’s metaphor on the last page: my leaves have drifted from me. All. But one clings still.

New medical theories suggest the working of puzzles, crossword or adult education help to slow down the effects of neurological deterioration. If that’s true my Wake obsession has simultaneously served up a double dose of medication. I highly recommend ignoring the naysayers and trying something new, something difficult.