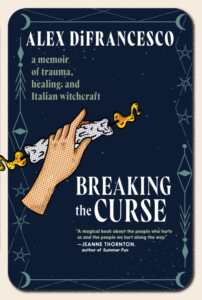

Finding What Works: Alex DiFrancesco on Transness and Spirituality

“I wanted something that I could claim as my own, something steeped in who I was as a person.”

The building was three stories tall and had apartments on every floor except the street-facing part of the ground one, where there were businesses. I didn’t notice, then, that the ceiling was collapsing in the third-floor apartment that the realtor showed to me, my eyes going instead to the recently finished floors and the huge amount of closet space he pointed out, rather than the imperfections.

This is the way it always is for me. I walk into situations seeing only what others want to me to see. There is a certain sleight of hand that I have to be on guard for, which I seldom am. I trust until there is proof that trust is not deserved. It puts me in a lot of situations I don’t care for, but what I would care for much less would be walking through the world with mistrust and prejudice.

This is the way it always is for me. I walk into situations seeing only what others want to me to see.

This is how it was when I moved to Cleveland, too. I had romanticized the Midwest, its crumbling buildings, its worn-down charm. It reminded me of home, I thought and often said, home being Wilkes-Barre, PA, a failing, decaying coal mining town. The sun would come up over the Cuyahoga River, and I’d drive across the sun-gold expanse of the water, over the bridge with its solemn guardian statues, seeing smoke billowing from factory buildings, ruins in the morning mist.

There was something beautiful about it, then. Something that filled me with hope and joy. There were times that I thought I’d live there forever. There were times I thought I’d build community. There were times when I believed the enthusiasm of the people who loved the city desperately, despite how they walked around in shirts with Cleveland emblazoned across the front, cheesily, like tourists, claiming Cleveland was “the best city in the world,” though they clearly had not seen much of the rest of the world. It was like home, I said, forgetting that I had left home long ago, for good reason.

I lived in Little Italy for around a year, in a back apartment of a building that, when fumigated, had insects that looked pre-historic lumber out of the walls. My neighbors were mostly old Italian men who hated minorities, myself included. My windows in my apartment were painted shut and the walls were thin, without insulation, as hot in the summer as living in a tent, and as cold in the winter as sleeping in a car. When I finally left, it was because a ground-level, painted-shut window had smashed when I tried to open it, the super hadn’t bothered putting a new one in, and the fleas from the cats that lived in the shed out back infested my apartment and my cat. I left the apartment like I’d found it, but worse: the sink full of dishes, the things I didn’t want any more piled on the floor.

Then, I was moving to the suburb on the West Side that everyone had told me I should have first moved to, the queer-friendly one that was like a little city in and of itself. I lived across the street from a dive bar that had karaoke seven nights a week. I would go after work or class every day and get wasted and sing through the new thickness testosterone had brought upon my vocal cords.

The ground floor of my apartment building hosted three businesses: a barber shop, a driving school, and a Santería shop. That first day, while I waited for the realtor, I walked into the Santería shop. I’ve always been a spiritual dilettante. Having rejected Catholicism at an early age, I have always loved reading about the world’s religions, trying to see myself fitting into them. Despite going deeply into Buddhism as a young person in New York City, despite almost converting to Judaism for my ex and her very religious family, I never found one that stuck. I walked into the Santería shop knowing a little bit about the religion from an ex from Cuba who practiced it.

The first thing I noticed was the replica Jobu in the window: the cigar-smoking, rum-drinking statue from the ’80s film Major League. Jobu was a made-up deity in the film, the idol of a Voodoo practitioner who believed that appropriate sacrifices to Jobu could make him hit a curve ball. To say that this didn’t exactly inspire my faith that this was a legit Santería store would be an understatement, but I walked in, anyway. I was in Cleveland, where tactless record stores put Black Lives Matter signs in front of cutouts of local celebrity Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. Cleveland, if nothing else, has a sense of humor about itself.

I’d spent years reading about transness as parts of spirituality around the globe, and yet the closest I came to finding something that fit still didn’t.

The guy behind the counter was white—another thing that made me pause. It’s not that I don’t believe there are white practitioners of Santería with African roots, it’s that I don’t believe white people without them have a right to the syncretized religions that enslaved Africans were forced to create from their own beliefs and their captors’. It’s like wearing a headdress or burning white sage: those practices are closed to outsiders who don’t understand their necessity. If I felt differently, I would’ve started practicing Candomblé or Santería years before. But I did not want something stolen, something “exotic” that I could wow my unknowing friends with. I wanted something that I could claim as my own, something steeped in who I was as a person.

I’d spent years reading about transness as parts of spirituality around the globe, and yet the closest I came to finding something that fit still didn’t: the feminiello of Italy. In Italy, these transgender women (transgender here being a catch-all and probably not how they would describe themselves) are seen as lucky, and babies are often brought to them shortly after birth for their special blessings. This was the nearest I could find to something I could call my own, and it still wasn’t my experience. For that, I would have to keep searching.

Still, I found myself suspending my disbelief and standing at the counter telling the man who worked there that I was looking for something to help my ex, the one who was a Santería devotee, who I hadn’t spoken to in a few years, and who was very sick the last time I spoke to him. His orisha was Shango. The man led me to a red and black candle with a white outline of axes and lightning bolts on it. Then, probably to upsell me in the terminally empty store, he suggested I not light the Shango candle without lighting one for Ogun, who would protect me from the harsh demands of Shango. I took both candles.

I told him I was looking for tarot cards, and for protection. I bought a gilt-edged set of cards that never once gave me a proper reading (in fairness, I never blessed them, either). I bought a St. Jude medal, the patron saint of lost causes, and pinned it inside my leather motorcycle jacket.

I walked out of the shop. I would end up taking the apartment upstairs, despite all the imperfections I still couldn’t see. When I would lay in bed at night, I could smell the incense burning from the Santería shop. It was probably all bullshit, white guy nonsense of pretending to be something he wasn’t. But when I lit the Shango candle, I lit the Ogun candle. I lit a candle that my witch friend Gabby had made for me: it had herbs and a picture of Baphomet on it. She had promised me that it would bring me all my desires. I pulled tarot cards. I kept pulling the Devil, gilt-edged and sinister, all the time.

__________________________________

From Breaking the Curse: A Memoir about Trauma, Healing, and Italian Witchcraft by Alex DiFrancesco. Copyright © 2024. Available from Seven Stories Press.

Alex DiFrancesco

Alex DiFrancesco is a multi-genre writer and transmasc person (they/them) who is the author of Transmutation, All City, and Psychopomps. Their work has appeared in New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, Tin House, Pacific Standard, Eater, Brevity, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and more. They are the recipient of grants and fellowships from PEN America, Sundress Academy for the Arts, and the winner of an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award for 2022. Their novel All City was the first awards finalist by a transgender author in over 80 years of the Ohioana Book Awards. They formerly served as an assistant editor for Sundress Publications in Tennessee, and currently edit LGBTQIA+ non-fiction for Jessica Kingsley Publishers. DiFrancesco lives in Philadelphia and is the human companion of a middle-aged, ill-mannered Westie named Roxy Music, Dog of Doom.