Finding Strange Magic and Unlikely Love During the Vietnam War

Lan Cao on the Beginning of Her American Life

My American life started with loss.

A few months before Vietnam fell to the Communists in April 1975, my father and an American family friend I called Papa Fritz took me in our black Opel sedan to Tân Sơn Nhứt airport in Saigon. I knew the route so well that the drive there, past streets shaded by tamarind trees and low‑slung buildings, felt normal, routine. My father was in uniform: camouflage fatigues, red beret, polished standard‑issue military boots. The city had been under rocket attack night and day. The streets, restless and swollen with people going about their business, were singed in smoke.

The last time the war was this close to us was during the Tet Offensive in 1968, and the memories of Tet’s devastation and its mix of the mundane and the deadly still frightened me. Tet firecrackers sounded exactly like gunfire, allowing the Vietcong to hide their attacks behind Tet festivities. Our house was in Cholon, which I thought of as Saigon’s twin city—Saigon’s other, shadow self. Our house was also close to the Phú Thọ race‑track, which had been seized by the Vietcong. Suddenly, the flat, open grounds where we used to watch horse races was the site of one of the fiercest battles of the Tet Offensive.

This seemingly innocuous area had become a strategic compound because it could also function as a helicopter landing zone and an artillery base. Americans and South Vietnamese forces fired thousands of rounds into the area, followed by house‑to‑house combat in the racetrack’s vicinity as the Vietcong tried to retake it. The noise was deafening. My cousins and I cowered in the bathroom in the back of the house while the grown-ups decided whether we could make it to Saigon, which was also under attack but less so.

This time, the fighting was not as close to our neighborhood as it had been in 1968. Still, we could feel the city shake when surrounding areas were shelled. After a particularly violent series of explosions that sounded close to our house, my father explained that the Vietcong had detonated a bomb‑storage area and destroyed an ammunition depot in Bien Hoa, about twenty miles from Saigon.

Even war can be normalized, especially a long war, like the one in Vietnam, which lasted more than twenty years. Sometimes it was very close to us and sometimes it was farther away. Throughout my childhood, the war pervaded my everyday consciousness, often with pointillistic precision. As a commander of South Vietnam’s elite airborne troops, my father was regularly away on combat duty for several days or weeks. He would come home and life would seem normal again, until the next combat operation.

Even when it was far away, the quiet engine of war could still be felt.

My first clear memory is of my body being swollen and itchy and feverish from chicken pox and my father picking me up and wrapping his arms around me. He pinned my hands, which were swaddled in cloth pouches to keep me from scratching. There was the smell of the earth and leaves and soil rising from his uniform. There was the small majesty of his by now familiar boots, which were big and still caked in mud. There was the low‑key lullaby that he sang to calm me, about a woman who held her child while waiting for her husband to return from the war. The husband had been ordered into battle by the Emperor. She waited and waited for him to return, for so long that she became a stone.

I knew the scars on his body did not come from schoolyard games. They came from a battle near the Cambodian border in which his troops were ambushed. I knew he had cyanide pills sewn into the hems of his uniforms, just in case he was ever captured or tortured. He would be able to bite the hems and swallow the poison even if his hands were cuffed. War made its mark on his body and his mind, and the ghosts of war stayed with us like whispered prayers inside our hearts, in the backs of our minds, in the marrow of our family consciousness.

Even when it was far away, the quiet engine of war could still be felt. Many of my father’s airborne troops were stationed right behind our house. My father told me the camp was off‑limits to me, but I often entered it secretly. All that separated it from our back garden, with its lush frangipani and lantana plants and bougainvillea, was a metal door, which I could open from my side because the troops often forgot to lock it from their side. And I would secretly spend time with the soldiers and was even allowed to touch their guns. Sometimes the clicking noises of the guns as cartridges were inserted and removed frightened me. Sometimes I saw one of the soldiers act boisterously, almost crazily, and he had to be held down by others as if they were fighting each other in an out‑of‑control brawl, but I was told later that they were doing this so they could console him.

Beyond our house it was also easy to be reminded of war. Outside our neighborhood at the Jeanne d’Arc Catholic church that stood at Six Corners, where six streets converged, there was always a young man with no legs—just one stump below the knee and the other above the knee—who sat on a patch of grass with his military medals laid out on a blanket, strumming a guitar and singing Creedence Clearwater Revival. “Have you ever seen the rain,” he sang in a grizzly rasp of a voice. I had perfect pitch, and I would go home to my piano and listen to the music hidden inside its body, appreciating always its intonation, its muscle memory, trying to eke out the right notes.

Sometimes when the urge to find the tune was uncontrollable, I even ventured into the church itself, past the vestibule and baptismal. There, you could smell the different aromatic oils used for baptism, confirmation, ordination. I would run past the nave, with its rows of dark polished pews, straight to the sanctuary, where I would find the piano nestled by the altar and tabernacle. The priest, with a strange expression—scowling, smiling, sneering, waving me in—was nearby. A small fan oscillated quietly, and his black robe fluttered as he coaxed me in. At a certain time of the day, every object in the church had a twin, rows of perfectly cast shadows, and despite the dark eeriness of the space, I allowed myself to go in because of the piano.

From there, in the somber quiet, I could hear the beggar man right outside singing. Like he was trying to recover God.

When the beggar man was not singing, he used his arms to propel himself across the sidewalk with alacrity, asking for loose change and telling people where he had fought. A part of me loved the frantic acoustic guitar licks, part sorrow, part pure ecstasy. Another part of me was terrified by what was unsettlingly not there—the missing body parts—and what was unsettlingly there—the tender stitched skin, wrinkled yet stretched over bony, fleshy nubs. I was transfixed by the songs that came out of his mouth—or, rather, out of some mysterious cavity deep in his chest—like the Rolling Stones’ “19th Nervous Breakdown”: “Here it comes, here it comes, here it comes, here it comes, here comes your nineteenth nervous breakdown.” It wasn’t fraught or foreboding like a threat, but more like the jangle of a promise. Whatever it is, here it comes.

Although my childhood markers all had something to do with the war, we managed to find normalcy in the interstices of daily life.

One of my mother’s beloved brothers was blown up by a mine while he worked overtime in a minesweeping unit. We called him Father Three, or Ba Ba, like a stutter. He was second in order of birth, but the firstborn was always referred to as the second to fool demons who had a tendency to grab a family’s first child. The mine had been cleverly wrapped in plastic or maybe was made of plastic; such mines are less expensive, more durable, and harder to detect. My grandmother went to collect her son’s splattered body—days later, she could still find bits of flesh under her nails and matted in her hair when she unraveled her chignon. His daughters vanished from our lives, as his widow was lost in her own madness and grief and wrath and stopped coming to visit.

My grandfather, a well‑known landowner in Sóc Trăng in the Mekong Delta, had been captured by the Vietcong and killed; landlords were deemed rapacious evildoers. They held him for quite some time, and my father had tried to parachute into the rumored vicinity to free him, but Grandfather could not be located. He might have been moved just before my father landed. Or he’d already been killed. I also remember my brother coming home one evening covered in blood because he had dined in a restaurant on Tự Do Street and a Vietcong on a motorbike had lobbed a grenade onto the patio. He was scolded for not knowing better. Right away, my parents instilled yet another lesson into us: Never sit at the front of stores or restaurants.

Still, there was an ebb and flow to living. Although my childhood markers all had something to do with the war, we managed to find normalcy in the interstices of daily life.

*

We didn’t just find normalcy, actually. We even found magic.

I daydreamed about magical things and had a magical view of the world, immersed as I was in the realm of dreams, visions, premonitions. In 1974, my older brother Tuấn was nineteen and enlisted in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, and my mother, worried about his safety, rushed to see a fortune‑teller. She left the house filled with anxiety but returned home feeling buoyant and reassured by a faint torch of hope. “The war will be over soon. Your son won’t be in it for long and he will be safe,” the fortune‑teller declared.

That was an extraordinary, almost magical statement, that peace was loosely feasible. The war, sprawling, wrenching, with its many twists and reversals, had been going on for twenty years with no end in sight. The supernatural notwithstanding, what the woman declared seemed wholly realistic. My mother believed her. “He will be safe” was a verse she kept in her heart. Tuấn was the soft, soulful type who loved to strum the guitar and sing love songs. His voice was deep and warm. He carried his guitar with him and made me wish my piano were portable. How wonderful that he could have his instrument with him anytime.

Tuấn used to sing with a band called Shotgun, and I loved his renditions of famous American songs like “My Way” and “For Once in My Life,” French songs like “L’Amour C’est Pour Rien,” and other Vietnamese songs of the melancholy kind my mother loved, such as those by Khánh Ly and Thanh Tuyền. Tuấn was not a soldier or a warrior, in other words. I knew he wanted to be a singer, which to my parents was just as bad as being an actor, or even worse.

The shadow side of life seemed so far away. I felt light and almost carefree. Even Buddhism seemed magical.

When my mother told me what the fortune‑teller had said, I was not skeptical either. I was happy to believe what my mother believed. It was magical but not impossible. Indeed, her prediction was correct, and my mother was granted the grim satisfaction of a magical wish come true. The war did end, although it ended with our loss. And my brother did survive, physically unscathed.

Even my father listened attentively when my mother told him what the fortune‑teller had forecast. He did not snicker, even though he must have known the facts. I was twelve, and my friends and I read the daily newspapers with a measured mix of dread and detachment. My parents did not flinch from real‑world discussions at the dinner table. The fact was that South Vietnam had been forced to sign the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, a peace treaty it didn’t want to sign because it allowed more than 145,000 North Vietnamese troops to remain in South Vietnam, ready to pounce and ambush when the Americans turned away. Our newspapers called it the “leopard spot” treaty. It didn’t feel like a real peace agreement, but it allowed the Americans to declare that there was now peace with honor—and that after a decent interval, long enough to absolve the United States, the North and even China could just come and claim us.

And after the treaty was signed, fighting continued as usual and intensified in the Central Highlands. Still, my father seemed to take my mother’s story seriously, as if he could allow himself a bit of magical thinking too. I happily took my cue from him.

My father devoted himself to yoga and Buddhist meditation. He told me that after years of practice, he had miraculously developed a secondary lifeline on his palm that ran parallel to the primary one. It was long, deep, and rosy. I ran my finger over it and felt its indented groove. I was happy because it signified that he had a strong spirit filled with vitality. Sometimes he invited me into his yoga room and we meditated together. The shadow side of life seemed so far away. I felt light and almost carefree. Even Buddhism seemed magical.

The One Thousand and One Nights stories my father gave me and that I read before bed, often surreptitiously under the blanket with a flashlight because it was past my bedtime, kept me alive in the fairy‑tale world of the fantastic and the fabled. I was enchanted by Scheherazade, who had a mythmaker’s understanding of the power of stories, which she told night after night to save her life. Her stories were fabulous, filled with mythological and phantasmagorical elements, and blended seamlessly with the wushu movies and novels that were beloved in Asia and Vietnam. We, both children and adults, were addicted to the acrobatic style of fighting and swordsmanship. We flocked to see their film versions the same way people today love the Harry Potter movies.

I threw myself on the bed with piles of books and followed their exploits. How I wanted to live in the Mongolian steppes.

As in the movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, male and female martial arts fighters in these films sail and somersault across rooftops and land on tree branches in spectacular defiance of the laws of physics. Poison‑tipped arrows fly with parabolic ease and hit the intended target straight on. Warriors unsheathe their swords and the crisp metallic blades glimmer. The hero or heroine, usually an orphan or a suffering child, must find a beloved teacher, a strict disciplinarian, a revered sage, just and fair, willing to impart fighting secrets so that the disproportionately more powerful enemy can be vanquished. The chosen disciple must exhibit a natural proclivity for a certain code of righteous conduct, one that celebrates humility and patience, respect and order, rectitude and loyalty. We children absorbed these values.

The most famous of all and the one I was most addicted to was a series of martial arts–themed books by the Chinese writer Jin Yong called Legends of the Condor Heroes, featuring two heroes, Guo Jing and Huang Rong. Guo Jing, or Quách Tỉnh in Vietnamese, was forced to flee with his mother to the desert after his father was killed by foreign armies; he grew up there with Genghis Khan’s Mongols. Huang Rong, or Hoàng Dzung in Vietnamese, is a beautiful, stratospherically intelligent, magnetic, and mischievous young kung fu fighter whose father was himself a legendary martial artist and who for mysterious reasons falls in love with the bumbling, not naturally gifted, not particularly dashing Quách Tỉnh.

I threw myself on the bed with piles of books and followed their exploits. How I wanted to live in the Mongolian steppes.

A wide cast of characters ranging from heroes to rogues roams across the pages. Who could resist the delirious charm and eccentricities of Quách Tỉnh’s martial arts teachers, the Seven Freaks of Jiangnan? My cousins and I took turns adopting their fabulous personas: the blind elder, best at staff fighting, dart throwing, and nighttime fighting; followed in descending order by six others who were connoisseurs of pickpocketing, fan fighting, horse riding and whip fighting, palm and pole fighting, spear and lance fighting and the youngest, the sole female among the seven, sword fighting.

Who wouldn’t be dazzled by such elaborate and intricate fighting routines, with fabulous names like Eighteen Dragons Subduing Palms and Nine Yin White Bone Claw?

__________________________________

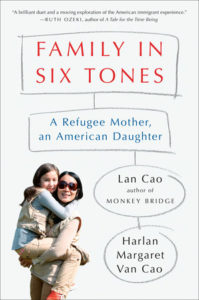

From FAMILY IN SIX TONES by Lan Cao and Harlan Margaret Van Cao, published by Viking, and imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Lan Cao and Harlan Margaret Van Cao. Photo: Saigon, 1967, Allen McKenzie.

Lan Cao

Lan Cao is the author of Monkey Bridge and The Lotus and the Storm, and most recently of the scholarly work Culture in Law and Development: Nurturing Positive Change. She is a professor of law at the Chapman University School of Law, and an internationally recognized expert specializing in international business and trade, international law, and development. She has taught at Brooklyn Law School, Duke University School of Law, University of Michigan Law School, and William & Mary Law School. Family in Six Tones is a dual first-person memoir, written by Cao and her teenage daughter Harlan Margaret Van Cao.