Spending a Night Alone in Mount Everest’s Death Zone

Jennifer Hull on One Mountaineer's Perilous Trip

Dave Hahn had turned back within 1,000 feet of the summit of Everest in 1991. (He would do so three more times, in 1998, 2001, and 2002.) The first time he reached the top was in 1994 in Tibet, on Everest’s North Ridge. Stymied by high winds, the first two waves of guides and climbers from his team had returned unsuccessfully from their attempts at a summit. When the winds finally quit, Dave led the next wave of five guides and three clients on a summit push from Camp 4, departing at around 4 am. By the time Dave pulled into Camp 5 with a lagging client who was going to have to turn around, it was 5 pm. Within minutes he was informed over the radio that their sherpa team, after stocking Camp 6 (their highest camp) in preparation for their summit bid, had mistakenly returned with an Italian team’s oxygen bottles and sleeping bags, assuming they had been left behind. Dave decided that instead of climbing into the tent with the others at Camp 5 to rest, he would try to repair the damage of his own team’s mistake by continuing up to Camp 6 with oxygen regulators and tanks for the two Italian climbers attempting their own summit bid.

It was snowing, and having been to Camp 6 only once before, three years earlier, Dave struggled to find his way. Partway there, his job was made easier when he ran into one of the two Italian guides and a sherpa descending. Due to the language barrier between them, Dave and the Italians relied on their base-camp teams to communicate for them over the radio. It was decided that Dave would continue up to Camp 6 where he would join the sole remaining Italian climber for a summit bid. By the time Dave finally found Camp 6, it was 1 am. He crawled into the tent where the Italian climber, Giuliano, handed Dave a pot of warm liquid. Exhausted and thirsty, Dave gratefully guzzled it down. They pantomimed to communicate with each other. Dave helped set up Giuliano with the oxygen apparatus he had carried up with him. Then they worked together to sort out a tangle of rope, spiraling it into a coil they could use for fixing the route, and left the tent by 3:30 am, bound for the summit.

For much of the next ten hours, as Dave navigated hairy vertical climbing sections with ratty, old fixed rope and traversed terrifyingly narrow fins of ridges, with 9,000-foot drops, that allowed room for just one foot at a time, he repeated a single instruction to himself: “Don’t fall!” When he finally reached the top of the second step in the early afternoon, after becoming totally mentally and physically absorbed in the task of propelling himself from the top of a rocking ladder up to a chest-high ledge, he realized that he and Giuliano had been separated.

When his team informed him via radio that the Italian climber had made the decision to turn around, Dave reassessed. He suspected that Giuliano had felt a bit off and therefore had made the right call by heading back down. It was late in the day, but Dave was still feeling good, and he suspected the rest of the climb would get easier. He made the decision to go on.

Dave Hahn knew well that the air in the Death Zone does not contain enough oxygen to sustain human life.It did not get easier. Dave struggled to find the rock with his crampons in the knee-deep snow and felt like he had to virtually swim up the steep, exposed slopes of the final pyramid. When he stood on the roof of the world for the very first time, it was 4:50 pm. Dave did not feel elated. He was alone, exhausted, and out of oxygen in the Death Zone, and he was entirely focused on how he would make his way back down.

The Death Zone is the name used by climbers for the region of Everest that stands above 8,000 meters, or 26,000 feet, at the very edge of Earth’s troposphere. Dave knew well that the air in the Death Zone does not contain enough oxygen to sustain human life. At such extreme altitude, digestion starts to shut down and the adrenal glands, which control vital bodily functions such as heart rate and blood pressure, begin to fail. Starved of oxygen, the brain swells and the lungs collect fluid. The body begins to die. The regulators on the tanks used by climbers typically release oxygen at approximately a 2-liter flow rate mixed with ambient air; it is not pure oxygen and does not come close to bringing climbers’ oxygen saturation to sea-level concentrations, but it is enough to offset some of the effects of exertion and to help prevent frostbite in the extremities.

As he hurried to descend, Dave tried to follow his own footprints, but the falling snow had already hidden them. He knew he needed to make his way back down through the most technical sections before he lost all daylight, but by the time he stood at the top rung of the ladder at the top of the Second Step, it was already dark. He turned on his headlamp and persisted, rappelling down the lower part of the Second Step. Disoriented in the weather, he grew frustrated when he found himself on dead-end ledges. At 1 am, at the top of the First Step, he reached the half-bottle of oxygen he had stashed on his way up, but he soon realized he must have put the regulator on incorrectly when the oxygen in it lasted only long enough for him to get down the First Step. At the bottom of the First Step, having finally reached what should have been easier terrain, he was without oxygen and his vision was still limited to the 6-foot circle of light provided by his headlamp in the snowstorm. By 3 am he felt so mentally and physically exhausted, he was certain he would fall off the face of the mountain if he continued. He radioed his team at Base Camp and told them he was going to try to wait where he was until daylight.

Dave found a spot out of the wind and sat down on his backpack. He tore open a packet of hand warmers and replaced the climbing gloves he was wearing with mittens. Dave knew if he fell asleep he would die, so instead he maniacally stomped his feet and shook his hands, to try to ward off frostbite, and screamed, “Ayeayeayeayeayeayeaye!” at the top of his lungs for hours, until he noticed the light beginning to return at 4:30 am.

Soon after, while talking on the radio with his worried friend, Curtis Fawley, who was 15 miles away at Base Camp, Dave saw another teammate, Bob Sloezen, who had been sent to help Dave, pop his head out of a gulley. Dave, not wanting to be in need of rescue, jumped up and deliriously attempted to make small talk. Bob slipped his oxygen mask on Dave right away and helped him descend to a tent at Camp 5, where another guide, Heather Macdonald, placed mugs of water in both of Dave’s hands. Dave found it a challenge to drink the water before he passed out. He had been awake for sixty hours. The last thoughts that drifted through his mind before being overcome by sleep were amazement that his feet were unharmed and that he had survived, followed by a dim realization that he had also made it to the summit.

A couple of days later, while tromping down the remaining 12 miles to Base Camp, Dave began to grasp just how beaten up he was by the experience. Every muscle in his body ached, and he was surprised to find he was peeing blood, from the toll the Death Zone had taken on his kidneys. Still, as he trudged wearily into Base Camp, he felt replenished by the welcome from both his team and the Italians and by the knowledge that he had reached the top.

Out of the nine expeditions so far that season, Dave was the only who had both made it to the summit and managed to come back down. He realized that if he had ever harbored a death wish, surviving a night alone outside in the Death Zone on Everest had squelched it. He did not want to know what it would take to kill him.

__________________________________

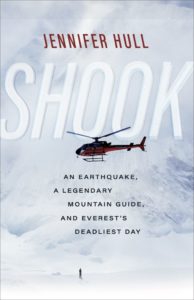

From Shook by Jennifer Hull. Used with the permission of University of New Mexico Press. Copyright © 2020 by Jennifer Hull.