Finding Grim Lessons of the 20th Century (and a Little Hope) in the Writing of Maria Janion

Marta Figlerowicz on an Unsung Thinker and Writer About Fascism and Nationalism

I came across Maria Janion’s Uncanny Slavdom on the verge of the 2020 lockdown. The title caught my eye. Sigmund Freud defines the uncanny as the nagging presence of the familiar within the strange, the strange within the familiar. That’s certainly how I felt those days. Standing in lines for toilet paper, watching the supermarket shelves empty out of everything except condiments, I might as well have been back under Soviet communism.

I grew up in the 90s in a relatively conservative pocket of late communist, then early post-communist Poland. At the time, the West seemed like a dreamscape, a vision of the future to which my region was belatedly trying to catch up. Given the opportunity to move to the United States for college, I eagerly took it. I felt I needed this new, more advanced-seeming environment to make sense of many things: my emergent queerness; the combination of neoliberal and socially conservative politics I was raised in; the broader cultural histories whose breadcrumb-trails I’d tried to follow in my local public libraries.

Abroad, my horizons had broadened; but by 2020, cracks were starting to show in this new world I’d idealized. Democracy, civil rights, social safety nets—it turned out they could all erode and slip away, pulling the Western spaces around me back toward the ones I had remembered from my Eastern European childhood.

Abroad, my horizons had broadened; but by 2020, cracks were starting to show in this new world I’d idealized.

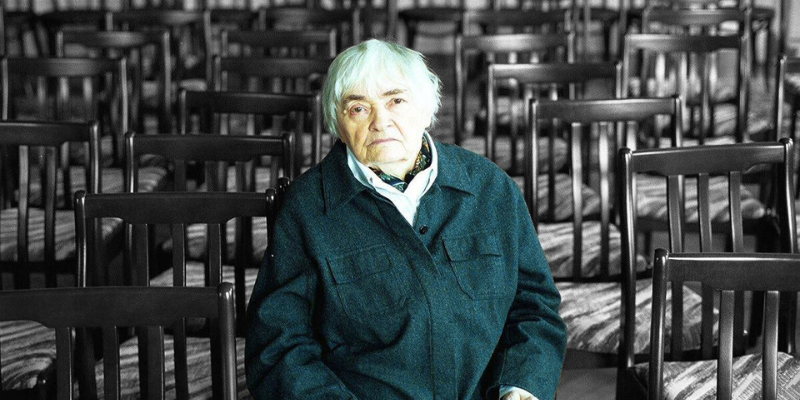

I flipped through Janion’s book, then couldn’t stop reading. Born in 1926 in present-day Lithuania, which was then part of Poland, Janion experienced the traumas and displacements of World War Two and then the rise and fall of the USSR. As a teen, she witnessed the genocide of Vilnius’s Jewish population in a nearby forest. Raised by a single working-class mother, she had no hopes of attending high school, let alone college, until the postwar communist government made it possible for non-elite students like her to do so. Her stellar record at the university of Łódź rapidly tracked her into an academic career.

These early experiences made Janion a lifelong leftist and, at first, an eager member of the ruling communist party. As she grew older, she became critical of the Soviet regime. Unlike many other dissenters, however, she refused to leave Poland for the West. She felt she owed it to the younger generation to stay on and instruct them; she also mistrusted the liberal West’s easy sense of superiority to the so-called Second World. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Janion famously cautioned Poles to not lose their cultural sense of self in their rush to rejoin the broader European community. “We must bring our dead along with us,” she quipped, lest we repeat the region’s old historical errors.

Uncanny Slavdom first came out in 2006. Reading it in 2020, I felt its prescience and deep relevance not only as an Eastern European, but also as an aspiring Westerner whose sense of the upward arc of twentieth-century history was crumbling. Janion speaks with deep erudition and personal experience about Eastern Europeans’ complicated historical identity.

Memorably describing her countryfolk as “east of the West and west of the East,” she names and narrates the region’s difficulty in establishing a stable cultural identity—or in identifying firmly with a neighboring cultural framework. She also speculates why, and how, such a sense of cultural unmooring can give rise to extreme nationalist and even fascist thinking, as a healthy sense of connectedness to one’s past twists into fantasies about cultural exceptionality.

My restless longing for the West and sense of alienation from it—but also the political frictions and rising nationalist energies I felt around me on the East Coast—they all felt named, diagnosed, seen in Janion’s careful prose.

My restless longing for the West and sense of alienation from it—but also the political frictions and rising nationalist energies I felt around me on the East Coast—they all felt named, diagnosed, seen in Janion’s careful prose. During the lockdown, in between zoom meetings and childcare, I absent-mindedly googled Janion’s other essays. I looked for English language versions that I could share with friends but couldn’t locate any.

Midway through 2020, Janion passed away at ninety-three. Reading long retrospectives of her life and work in the Polish press, I began to appreciate what a huge presence she had been in Eastern European intellectual life. This was the kind of person I’d foolishly assumed I’d never get to meet in Poland because of its supposed cultural belatedness. A world-class, cutting-edge thinker who seemed to have read everything, wrote copiously, and explained the complex political and cultural world I had been swimming in. A person who had lived through twentieth-century historical traumas whose specters haunted my own, younger generation and could speak to the present from within this long historical perspective. A queer woman who knew what it was like to not take one’s personal and sexual freedoms for granted.

“She haunts you,” Janion’s literary executor observed in one of our early emails. Having just barely missed Janion’s physical presence, I was determined to make sure my English-speaking communities did not miss her insights. One reason why Janion’s acumen has not previously received much attention overseas is because she spoke to, and of, a world the West had thought it was leaving behind. A major theorist of fascism, nationalism, and collective fantasizing, her thinking has arguably become more urgently relevant than ever.

As I compiled a selection of Janion’s essays into The Bad Child: A Maria Janion Reader, I did so with this newly sensitized Western reader in mind: someone to whom the mechanisms and legacies of twentieth-century political upheavals have suddenly become immediately pertinent, for whom the question of national identity—and whether it is possible to separate national pride from fascism—has become increasingly fraught and pressing.

I turned to her as a reader, and then embraced her as an editor and translator, because she helps me see ways forward and beyond where we currently are.

When I embarked on translating Janion’s work, QAnon protesters had recently invaded the Capitol; by the time it was going into copyedits, Trump had just won his reelection. How can we change this America, and, as importantly, how can we care for an America that has become this? In Janion’s writing, such questions are inextricable from each other: fascism and xenophobic nationalism can only be overcome by equally strong alternative forces of collective cohesion and self-affirmation.

In pieces on patriotism as a kind of madness, on the long history of Polish and Russian colonizations and cultural appropriations of Ukraine, on the ways communities fantasize and share their daydreams, and others, Janion creates wormholes between past and present. Nowhere is her continued relevance more keenly felt than in “The Patriot-as-Madman,” a brief but powerful essay about the logical and affective paradoxes of patriotism:

This patriotic feeling overwhelms his thoughts, attitudes, values, and personality as such; all other motivations fade into the background. Transgressive and exaggerated, it hovers on the brink of madness; a bystander could diagnose it as a self-aggrandizing psychosis that pushes the patriot toward self-destruction and death.

A lifelong scholar of Romanticism, Janion is no stranger to irrationality; over the years, she also developed an extremely subtle language for describing its various shades and motivations. Patriotism, she argues, is necessarily irrational as a non-logical preference for one country over others. How, she asks, can one prevent this irrationality from sliding into a reality break?

Janion’s analyses are trenchant but also hopeful. She describes her brand of leftism as “Promethean socialism”: a brand of socialism that believes in the perfectibility of human beings:

It all comes down to how we understand human nature. Did we commit original sin? Are we always at war with one another? Either of these original conditions would compel us to curb our aspirations to self-making, self-saving, and self-liberation as harmful forms of willfulness. Still, in practice, neither of these concepts of humanity accords sufficient weight to the condition of the oppressed, the suffering, the humiliated, and the persecuted … Empathic attention to the marginalized has always been the domain of Promethean socialism, since it assumes that humans are not intrinsically evil.

Amid our current political polarization and mutual animosity, such a view of our species might seem starry-eyed; it seemed no less naïve to critics when Janion wrote this essay amid the Cold War. Still, she refused to budge: change is not possible, she argued, without hope for a better future, and without trust in ourselves as its aspiring agents. I turned to her as a reader, and then embraced her as an editor and translator, because she helps me see ways forward and beyond where we currently are.

__________________________________

The Bad Child: A Maria Janion Reader is available from the University of Minnesota Press.

Marta Figlerowicz

Marta Figlerowicz is professor of comparative literature at Yale University. She is a Guggenheim Fellow and author of Flat Protagonists and Spaces of Feeling as well as more than a hundred articles, reviews, and essays. Her translations from Polish have appeared in PMLA and The Paris Review.