The Wonder of Collaboration: Finding a New Spark of Creativity with Liana Finck

Luke Burgis on Balancing Distinct Voices and Desires

I reached out to Liana Finck during the early, dark days of the pandemic in April 2020. My fiancé, Claire, insisted that I do.

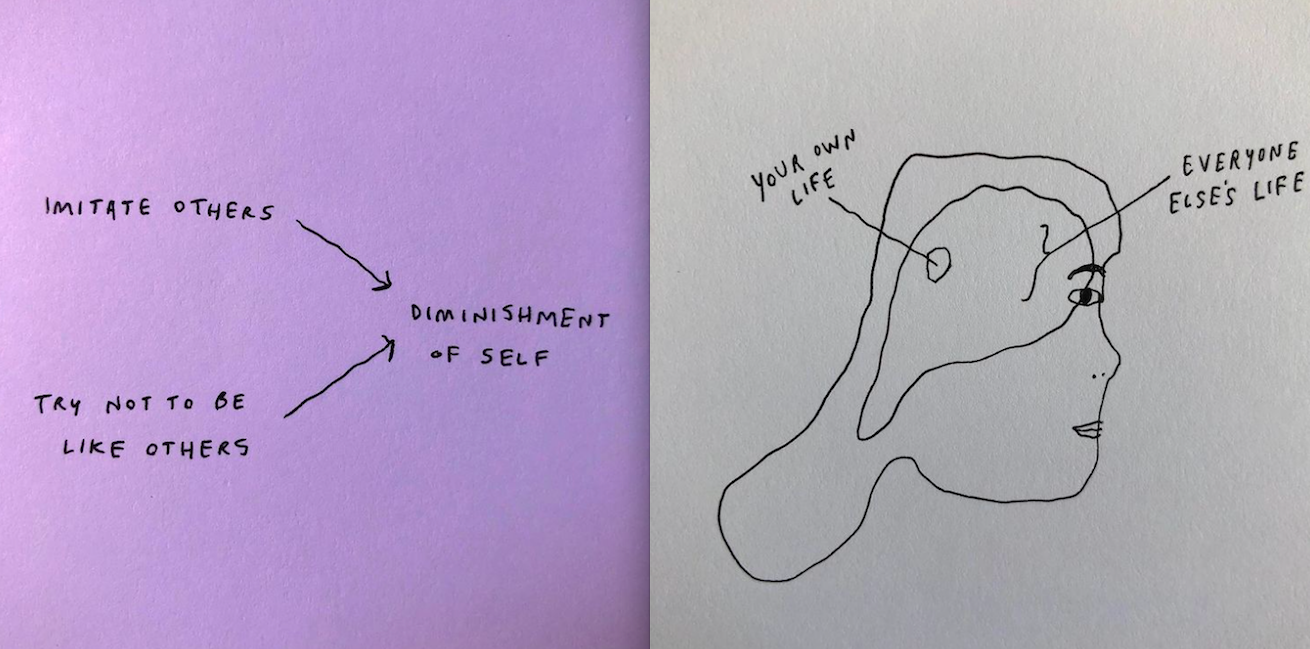

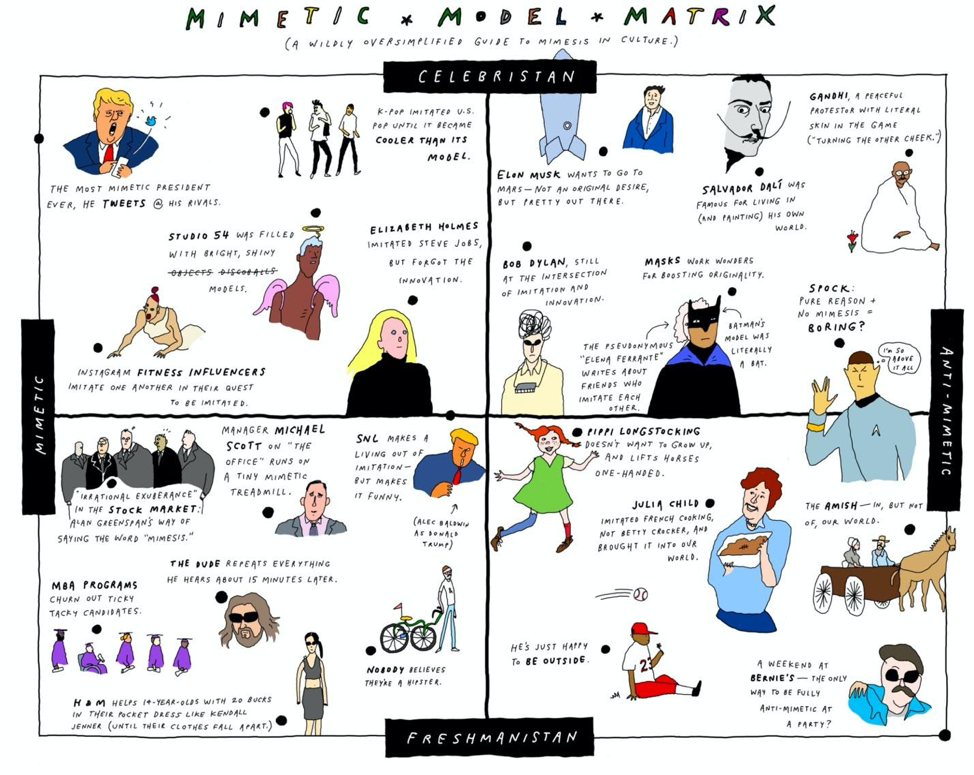

I had realized that my nonfiction book, Wanting—a book about a social phenomenon called mimetic desire—needed simple illustrations to reinforce its ideas. I’m such a visual thinker that I knew I would benefit from someone who could help me “see” the ideas in new ways. And I was betting that my readers would benefit from it, too.

The drawings needed to be no-frills, witty, biting, and thought-provoking to balance out the sometimes heavily philosophical nature of the text. I wanted art that would complement the writing, not just supplement it—art that didn’t seem like a business class diagram or an unnecessary appendage.

Claire—along with hundreds of thousands of others—followed Liana on Instagram. Her work regularly appeared in the New Yorker, and she had just drawn the cover of Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande’s new single, “Alone Together.” More importantly, Claire said, it was like her drawings seemed to be winking about the very thing my book was about: mimetic, or imitative desire: the idea that our desires and identities are shaped by what other people want, the hidden dance of desire that influences our choices. When I first laid eyes on Liana’s drawings, I felt deeply understood—which is odd, considering that I’d never even met Liana or seen her work before. But there was something foundational to human experience that her art and my writing was trying to capture.

Drawings on Liana Finck’s Instagram.

Drawings on Liana Finck’s Instagram.

Based on what Claire showed me, I thought there was a chance that Liana would be interested. But even if she was, it seemed unlikely that she would give me the time of day. She had over 500,000 engaged followers on Instagram; I was still bugging Claire to show me how to properly post a story.

At the time, Claire and I were holed up in an AirBNB in Michigan that we had submitted a longshot offer for—we asked for a 90 percent discount to the regular price for a house perched 100 feet above the rugged shoreline of Lake Michigan, and the owner had inexplicably accepted. We moved into the place to isolate and protect my parents from our cheeky trips to the corner store (at that point, we were still giving a Lysol bath to our boxes of pasta.)

It turned out to be our dream home, which partly shielded us from the harsh realities on the ground. On our back deck, we witnessed twice daily flyovers by a bald eagle we named Caesar.

Given the unexpected surprise of our lake house, and seeing that we were still in those early days of martini-Monday, Tuesday, Wednesdays, and Tiger King—and still optimistic that it would all be over in a few months—I was feeling lucky. So I shot my shot and sent Liana an email asking her if she’d like to illustrate a non-fiction book about the ideas of an obscure French academic.

Her reply came quickly: “Hi Luke, I don’t think so, I’m too busy, I’m sorry.”

Sometimes I feel I know the right fit when I see it. This idea runs contrary to one of the main ideas in my book (that most desire is socially-derived) and also to the idea—especially prevalent in the startup world where I come from—that the value of something is directly proportional to the amount of competition for it, or to the amount of data points I collect before making a decision. It’s the fear that if I don’t shop around to four or five different artists and put them through a dog and pony show for the opportunity to work with me, then I might be choosing the wrong person.

No—I had to only look at Liana’s work to see the striking correlation between the topics she was drawing and that I was writing about, and the search was over. I had already started working with a stellar illustrator at that point, but I knew I had to pivot as soon as I saw her work. I imagined it was like a movie director meeting the perfect person for a role on the street and scrapping all previous plans due to a gut instinct.

So I persevered. I checked in with her a couple of times to see if she was “less busy”, and made my fumbling attempts to explain mimetic desire in an email and tie it to her work. She finally asked to see a manuscript, maybe out of exasperation.

I was nervous about sending such an early draft. The final chapter hadn’t even been written at that point. And I wasn’t just insecure about the quality of my writing; I was also nervous about something in my work offending her for some reason (and no particular reason at all). It seems that we live at a time of extreme skepticism and fear—people often choose to work together only if each views the other as having passed an ideological purity test. One bad or uncharitably-interpreted sentence and my shot at collaboration would be over, I thought.

I imagined it was like a movie director meeting the perfect person for a role on the street and scrapping all previous plans due to a gut instinct.

In my view, a big factor in what is commonly called “cancel culture” is mimesis: people mimicking the moral outrage of others without having seriously arrived at that level of condemnation themselves, even while they are under the illusion that they have.

“I️ say ‘yes’ to paying jobs that seem legit and like they won’t get me cancelled,” Liana wrote me recently when I asked her how she makes decisions about who to work with. So my suspicion was not entirely unfounded.

We’re all walking around thinking that one finger pointed in our direction could lead to a cascade of other accusatory fingers, and it might simply be due to a loose association at some point in the past. (Whatever happens in the economy, there will be a bull market in background checks.) The cultural downside of all this is this: as everyone shaves the sharp edges off their statements to some lowest common denominator of acceptance, we’ll lose the ability to say anything inconvenient or important. But that’s a story for another day.

Liana assuaged my worst fears, though. She came back gracious, friendly, even enthusiastic about working on the project with me. She grasped the core idea right away: humans have a natural ability to tune into what other people want, and we engage in a complex game of imitation that is the edifice of our social lives. Our powers of imitation are what allow us to quickly form bonds with other people—and that works in both positive and negative ways.

“I️ don’t think I’m particularly tuned into mimetic desire,” Liana reflects, “which explains why I had trouble making friends at school. I️ think I’ve learned to try and follow the herd more as an adult, but it’s not so natural—which means in some ways that I️ do it too much. Like, is this how I’m supposed to do it?’ It doesn’t come from genuine desire. Also, it nicely explains the greed of the world around us. People say this comes from capitalism but I️ wonder if it isn’t just an inborn human trait in some ways. A gross one.”

Some people say that if God doesn’t exist, we’d be forced to invent him. Maybe we could say the same thing about capitalism: if it didn’t exist, humanity would have a psychological need to invent it. People would still need some way to keep score—some way to know what other people want, and how much they want it.

No doubt there were some market forces at work in my collaboration with Liana. She was technically “work for hire” (meaning I paid her well). I also thought that her art would enhance the quality of my book and help it sell more copies. At the same time, my decision to pursue the collaboration transcended the calculus. The money that I paid Liana came out of my own pocket, not my publisher’s, and I had already decided I was going to spend it to improve the reading experience regardless of whether or not I recouped the cost. I was confident that Liana would spark new creativity in me. Maybe I was paying for that spark.

I don’t know what I don’t know. But I do know that I don’t know a lot of things—and I know that my perspective is limited.

I don’t know what I don’t know. But I do know that I don’t know a lot of things—and I know that my perspective is limited. In order to open up new horizons of my work, I intentionally seek out talented people who bring a different view to the table. If the idea that I’m talking about is truly universal (and I thought that it was, in this book), then it should be a diamond with 7.6 billion sides.

I saw little value in trying to tell Liana what I wanted. I usually don’t know until someone shows me. “You gave me a lot of freedom to come up with the ideas I️ wanted to,” Liana tells me.

In my experience, collaboration works best if there is a meeting of desire. If two or more people truly want to contribute something to a project, their creation comes alive. Even if money changes hands, it is the shared desire that yields a result that is greater than the sum of the parts. Without this meeting of desire, collaboration can seem transactional or stale or come off as completely market-driven. For example, the MSCHF ideas factory—the art collaborative behind Lil Nas X’s notorious “Satan Shoes” and other viral product drops—is designed to generate the maximum amount of mimesis in the market without necessarily tapping into the desires of each creator. When that happens, I think we lose something important.

In the new Creator Economy—especially the world of digital creation, non-fungible tokens, and the shifting landscape of publishing—good collaboration will be crucial. There’s no strong ecosystem without strong collaboration. And decentralized shouldn’t mean individualized. We can bring out the best in one another, but that only happens when we’re working toward something that is born out of a deep desire.

“I’ve been working a bit more collaboratively than usual this year,” Liana tells me. “On a screenplay I️ tried to do all by myself but botched, so am now working with another person, and on a TV show, where I️ have two EP’s, one belonging to the TV network that hired me and one a kind of guardian angel. It’s been fun. I️ guess I’m slowly learning how collaboration is a bit different from work for hire.”

I suppose I had a glamorous view of collaboration because I grew up listening to hip-hop. Someone would show up and rap the best verse on someone else’s track. Jay-Z was one of the best to ever do it. In 2004, he collaborated on an entire album with Linkin Park. The next year he appeared in the second verse of Kanye West’s ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ and said “I’m not a businessman; I’m a business, man.” I never forgot that.

I’m sure Liana would be endlessly amused by my suggestion that she rapped one of the hottest verses on my album, but that’s a little what it felt like to me. You give someone the freedom to put their own stamp of creation on your work, and it ends up turning into a shared creation which surpasses anything that would’ve been possible for either one independently.

“What are some of your favorite collaborations (besides ours, of course)?” I ask Liana. “Ooh. One of my favorite graphic novels is From Hell—a collaboration by the super-organized Alan Moore and the wonderful intuitive Eddie Campbell. I’m also a big fan of adaptations. I️ love Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, which is an adaptation of E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End. There’s so much freedom in channeling another person. I️ think this is probably the wonder of collaboration—two people studying and reacting against the ways each other’s brains work.”

Studying and reacting against the ways that Liana’s brain works was especially freeing for me, partly because we didn’t communicate face-to-face, or on Zoom, (which we both expressed a disdain for in our initial emails), or even via phone. The dreaded “let’s hop a Zoom” email just never happened, and we found ourselves at the end of the project having never spoken in any way other than through our respective work—my words, her art—until my wife and I finally met up with her on a grassy knoll in Prospect Park on a beautiful fall day in 2020, six months after my initial email.

By that time, I already felt like our minds had been playing off each other for months. We were in some sense spared from all of the initial awkwardness of trying to get to know each other first, and maybe the exhausting nature of that process would’ve taken away from our energy of trying to create something coherent and cool. We jumped straight into the work and never looked back.

I suppose that’s because Liana never requested to talk at the beginning of the project. The words in my book spoke for themselves, and she would respond to them by sharing a piece of her brain in art. I was freed from the expectation of all of the social proof stuff that typically happens in work relationships. We developed our own little culture or way of working together—a different form of communication that was incredibly satisfying for me. I believe it’s because we gave the other person the freedom to create what they wanted to, without imposing too much. We maintained our distinctiveness, but we came together to make something newly distinctive.

That’s the real wonder of collaboration: that two minds in two different bodies with different experiences of the world can create something entirely new in the world—something that goes beyond anything that existed in either one of those minds at the beginning.

One of the feature drawings in the book, by Liana Finck.

One of the feature drawings in the book, by Liana Finck.

Luke Burgis

Luke Burgis is the author of Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life. He’s Entrepreneur-in-Residence at The Ciocca Center for Principled Entrepreneurship, where he also teaches business at the Catholic University of America. Luke has founded multiple companies. He holds a B.S. from the Stern School of Business at New York University and graduate degrees in philosophy and theology.