Finding a Forgotten Book On Surviving the Holocaust

P.N. Singer on rescuing his grandfather's book from oblivion

The Discovery

In the attic of a suburban house outside London in the 2000s, my brother made a remarkable discovery: a folder containing 200 fragile pages, typed in German, dated 1945, and apparently placed in a suitcase and never touched since. Its first page bore the name Moriz Scheyer and the title Ein Überlebender (A Survivor).

We were clearing out the old family home: our father, Konrad Singer, needed to downsize. The attic—in the way of attics of family homes lived in for 40-plus years—had accumulated detritus gradually throughout that period (garden furniture, books, toys, bedlinen, kitchenware), without apparently ever jettisoning any.

In the midst of all that was this incredibly valuable, irreplaceable document. The written account of a family legend: my grandparents’ wartime flight through France, involving incarceration, hairsbreadth escape from deportation, and a final heroic rescue by a French family and improbable concealment in a rural convent. A story which had always been recounted to us as extraordinary, even miraculous—but in fragments, the details unclear or forgotten, the original protagonists silent.

In the midst of all that was this incredibly valuable, irreplaceable document. The written account of a family legend: my grandparents’ wartime flight through France, involving incarceration, hairsbreadth escape from deportation, and a final heroic rescue by a French family and improbable concealment in a rural convent. A story which had always been recounted to us as extraordinary, even miraculous—but in fragments, the details unclear or forgotten, the original protagonists silent.

As I turned the first page, and was transported back to the beginning of that story—to Vienna in February 1938, immediately before the Anschluss—I was also meeting a family member for the first time. Moriz Scheyer, my father’s stepfather, a well-respected literary figure of 1930s Vienna, and a friend of Stefan Zweig, who died long before I was born.

Conflicts of Memory

The find raised problems, too. The obvious ones, of course: the need for careful translation and research, the question of finding a publisher, of whether the book would interest people without a personal connection as much as it did me. But there was another issue—one connected with the reason that the find had been so unexpected. And that was that I knew the book to have been destroyed. And the reason I knew that was that my father had told me so: he had himself destroyed it (or thought he had).

At the time of that revelation—when, some 25 years before the discovery, as a teenager, I had begun to be intensely curious about this lost side of the family and the family history—I was incredulous, even angry. How could my father have been so uninterested in preserving this historical document, his own stepfather’s account of this extraordinary story?

He gave (at different times) two reasons: the “self-pity” he discerned in his stepfather’s account, and its uncompromising “anti-German” sentiment. Either judgment, in the context of what Moriz and his companions went through, may seem to us unbelievably harsh and unsympathetic. But that reaction does, I think, draw attention to something important—about the role of a generational dynamic in relation to family memory, and the conflicts of memory. First, there is the specific postwar context. My father was a young man in 1945, desperate to look forward, to create a new world—socialist, rationalist, free of racial and nationalist thinking—above all not to dwell on the catastrophes and terrible irrationalities of the immediate past. Moriz Scheyer, over 50 at the time of his enforced emigration, unable to build a new life, shattered in health and spirit, could do little but “dwell,” could only bear witness to that trauma.

There is also, perhaps, a broader issue: the difficulty the next generation has in dealing with or validating the perspective of their parents; or, indeed, of doing justice to the possible future interest of the next generation after them.

Moriz Scheyer’s book does indeed have a rare fury, an uncompromising, merciless tone. And that tone may at times cause us unease—as indignation at the monstrosity of the Nazi ideology and its implementation at times seems to spill over into racial generalization.

But is a voice that brings us immediately and undeniably back to the lived experience of the time. And it is for that reason, above all, that the book seemed to demand to be rescued from obscurity.

The Time Capsule

Because this is the uniqueness of the book. It is a time capsule. Unlike so many survivors’ accounts, written or produced through interviews decades later, this is a book where you cannot doubt that what you read is what someone experienced and thought at the time. That perspective, that reaction to the events, has been preserved unaltered for 70 years. It suffers no risk of false memory or suggestion, of distortion.

Sometimes the perspective is surprising, arresting, bringing the reader face to face with a different world view. How remarkable, from our 21st century, to read Scheyer’s view—leading him, doubtless, to despair of the book’s publication—that “no one will ever be interested in what happened to Jews.” Antisemitism, from his 1940s perspective, was so ingrained in European culture that an account of something that “only” affected Jews could never attract serious attention.

How poignant, too, not least now, to encounter in Scheyer’s writing the concept of the “good European.” A well-known phrase of the time, now long forgotten, it was bound up with the pan-European ideal (associated with another forgotten figure, Romain Rolland) of a culturally bonded brotherhood of nations. It was, arguably, despair at the fate of this ideal that drove Moriz’s friend Stefan Zweig to suicide in 1942.

Other perspectives are not in themselves surprising, but are brought before us with extraordinary vividness. Few if any other accounts of the period give one such a devastating, grueling, sense of what it was like. What it was like for a respected citizen and professional, aged 51, to lose status, job and home, overnight, in “his own” country. To scrabble around desperately for a possible destination country, a possible solution. And then, in France, the sense of outrage and disbelief: at the political naïveté, including of French Jews; at collaboration; at the mass executions carried out by the Nazis. And above all the sheer sense of everyday fear, of uncertainty, not to mention exhaustion, in a life of enforced travel, in middle age, in poor health, with the constant—and increasing—daily fear of a call in the night which will mean deportation to a death camp.

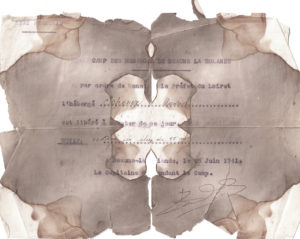

Document certifying Moriz Scheyer’s release from Beaune concentration camp, June 1941

Document certifying Moriz Scheyer’s release from Beaune concentration camp, June 1941

Then, there is the sheer extent of the historical events that it covers. Very few survivors’ accounts—I read a lot during my research—have anything like the range of this book. Simply as a function of the extraordinary sequence of events personally experienced, it serves almost as a comprehensive chronicle of the stages of the occupation and of the anti-Semitic persecution. The mood in Paris both immediately before and immediately after the fall; the “Exodus”; the first anti-Semitic statutes; the first round-ups, with a resultant period of life in a French concentration camp (Beaune-la-Rolande); life and political mood in the “free zone,” and the shady world of the “passeurs” who took money to conduct—or fail to conduct—people over the border. The characters and activities of the Resistance in southern France; life in hiding (in a convent).

Transience

Research on the book, and the book itself, taught me a lot about what my family and others went through. It also brought me constantly face to face with the fragility of memory.

The range of literary personalities we encounter in the book—all, at the time, famous and widely read, most now consigned at best to footnotes in a literary history—is itself striking. (And indeed the same could be said of the author himself.)

But most striking to me was the fragility, the precarious survival, of the story itself. I visited the scene of its dénouement, Belvès in the Dordogne. Nowhere did I find knowledge or memory of the story—of how three refugees from Austria were dramatically rescued and concealed here for the last years of the war. And that though I visited the convent itself, and though I spoke to a childhood friend and Resistance comrade of one the rescuers, Gabriel Rispal. And although Rispal himself was subsequently a well-known personality, both as film actor and as political activist.

Without the precarious survival of the typescript in a family attic, without its casual discovery in a house-clearance, that remarkable story, not just of human cruelty and suffering, but of unbelievable bravery and self-sacrifice, would be lost forever.

At an event at the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris, earlier this week, a group of French historians and writers held a discussion of the role of women in the French Resistance. The discussion focussed on two specific books. One was Moriz Scheyer’s Asylum, just published in French translation. It is extraordinary to imagine how Moriz himself might have reacted to such a validation—in the country which he loved, of which he despaired, and in which he died in 1949 with no hope of the book’s publication. A validation which has had to wait more than 70 years.

For that validation—for the voice the book gives, both to his selfless rescuers and to his fellow-internees who did not survive—the salvage has, surely, been worth the effort.

P.N. Singer

P. N. Singer (Moriz Scheyer’s step-grandson) is a writer and translator, who works with classical languages (Greek and Latin) as well as German and Italian. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took a Ph.D. in 1993, and has studied and lived in Italy, Germany and India. Alongside work as a literary translator, P. N. Singer has published on philosophy and history of medicine, with a particular specialism in classical Greek ethics and theories of the mind, and further interests in drama and performance practice. He currently holds a Research Fellowship at Birkbeck, University of London.

Moriz Scheyer (1886-1949) was arts editor of one of Vienna's main newspapers from 1924 until his expulsion in 1938. A personal friend of Stefan Zweig, in his own lifetime he published three books of travel writing, and three volumes of literary-historical essays. He died in France in 1949.