Finding a Beautiful Escape in Illuminated Manuscripts

Christopher de Hamel on Growing Up in New Zealand, Medieval History, the Book of Hours, and More

I was born in London. In 1955, when I was four, my father took a job in New Zealand and we traveled out with my brothers in what, I now realize, was one of the last of the government-assisted immigrant ships. It was an exciting adventure for small children and we sailed through the Panama Canal and stopped at Pitcairn Island. My father, a medical doctor with a passion for natural history, embraced the opportunities of New Zealand with delight. There are extraordinary birds and plants to be studied there which exist nowhere else and corners of the country were still unexplored. The kakapo, a chunky parrot from the dinosaur age, for example, was rediscovered still living deep in the Fiordland bush in 1958. My father took part in the Hillary-Fuchs expedition to the Antarctic in 1957-8, recording the domesticity of Adélie penguins.

Initially, however, my mother, an Oxford graduate who had taught languages and the history of art in central London, struggled greatly with the transition to the isolation of a suburban bungalow in Christchurch. New Zealand in the 1950s was a very long way indeed from the bustling metropolitan drawing rooms of her upbringing and from Westminster Abbey and the National Gallery. We were made to keep our English accents and never quite to integrate with New Zealanders. My elder brother and I both collected stamps with great enthusiasm. We each owned a Penny Black of 1840, sent by our grandparents in Surrey as the best Christmas present ever, and that same year, 1840, had marked the beginning of the British colony of New Zealand. Anything earlier than that was prehistoric.

In 1963 we moved to Dunedin, further down the South Island, a city which still preserves its Scottish founders’ respect for learning and their ethics of Presbyterianism. My mother was happier there. Within a few months I had discovered the Dunedin Public Library, a stately brick and stone building in the neo-Romanesque style opened in 1908 in Moray Place, following a Carnegie grant from Scotland. You would go into the entrance hall and double back up the wide wooden staircase on the left towards the upper floor. Halfway up was a kind of mezzanine gallery, parallel to the front of the building.

Along one side and in a little room down a step at the far end were glass display cases filled with precious rare books, including half a dozen medieval European manuscripts. It is hard to convey the thrill of encountering these, after the bright sunlight of the modern street outside. Here, for example, were two illuminated Books of Hours of the 15th century and three Latin Bibles of the 13th century, and part of a large lectern Bible of about 1320. They are still there, although the Library is now in a new building not far away.

In world terms they are not very important, but to me, at the age of 12 or 13, they were the most magical things I had ever seen, up to 600 years older than even my Penny Black. New Zealand, like America, has notable indigenous pre-history and an important place in colonial expansion and in modern politics and economics, but what it lacks is any equivalent of the Middle Ages. There are no medieval gothic cathedrals or ruined abbeys or ancient half-timbered houses as are found all across Europe. All they can realistically possess of the Middle Ages in New Zealand are specimen manuscripts, which are easily movable. These are uniquely European and they are genuine. I was utterly bewitched.

In world terms my library’s illuminated manuscripts are not very important, but to me, at the age of 12 or 13, they were the most magical things I had ever seen, up to 600 years older than even my Penny Black.

The collection in Dunedin had been brought together by Alfred Hamish Reed (1875–1975), a publisher and prolific author who had been brought to New Zealand from England as a boy and had initially moved to Dunedin as manager of a typewriter company in 1897. He was a tall flamboyant figure with wide mustache and thick white hair, something of a local celebrity in Dunedin, known for his intercity hikes and mountain climbing when well into his 80s and 90s. More relevant to the manuscripts, he was an evangelical Christian. He had cards printed, beginning, “I believe in the Gospel of work, of laughter, and of good-will to men.” There is a long tradition of Low Church book collecting. The belief is that early Bibles are tangible relics of the Word of God and they are witnesses to faith across the centuries. Mr Reed—he became Sir Alfred in his hundredth year—gathered Bibles and religious texts, as well as autograph letters of Christian hymn writers.

He began buying medieval manuscripts in 1919. By the late 1920s he had formed the idea of making the collection over to the Dunedin Public Library, supported eventually by a charitable trust that he and his wife established in 1938. Major items eventually came to include several pieces of a 9th-century Evangeliary, then the oldest Western manuscript in Australasia, a leaf of a Gutenberg Bible, and a precious 15th-century illuminated manuscript of the Wycliffite translation of the Gospels into Middle English, bought at Sotheby’s in 1956 for £560. With hindsight, that was his fi nest purchase.

One day I was gazing into the glass cases when old Mr Reed himself appeared. He was by then very deaf. “Do you like what you see?” he boomed, in a voice which caused every head in the Library to lift. Oh yes,” I whispered, overawed in his presence. “What’s that?” he shouted, cupping his hand to his ear, “Speak up, boy!” I think the librarian had already told him that someone was actually looking at his displays. He ordered the staff to open the vitrines for me, and I touched and smelled medieval parchment for the first time.

At first, I suppose, it was the artwork which entranced me most, as well as the antiquity of the books. Encouraged by the bemused and tolerant library assistants, I used to come in also to copy the red and blue decoration of the manuscripts’ initials, and I practiced making illuminated borders with their little gothic ivy leaves and scrolling decoration. A whole Saturday afternoon could disappear happily as I sat hunched absorbed over the table in the old Library’s upstairs reading room, with the original manuscripts beside me.

Medieval manuscripts were always my secret escape from a world view seemingly dominated by raucousness and rugby.

I copied some, not well, into my school books. A number of manuscript cuttings in the Library were kept in frames hanging on the stairs and (I cannot think why I thought they might agree) I asked whether I could borrow these, like other library books. There were urgent conversations in the Library office, and they decided that they could think of no reason why not, if I promised to be careful. I thus came home with two of the framed leaves of that 9th-century Evangeliary on the school bus, to the astonishment of my parents. My mother persuaded me to invite Mr Reed home for tea, and, probably equally curious, he came. He was a vegetarian (I am not sure I had met one before) and a teetotaler. He was a great raconteur. I recall that he, knowing we were from England, told us how as a boy during the British general elections of 1885 he and his mischievous friends interrupted local Conservative meetings by shouting “Vote for Gladstone!” and then they would run into the nearby Liberal headquarters calling “Vote for Salisbury!” Here was Victorian history being related first-hand in our New Zealand sitting room.

I was at that time a pupil at King’s High School in south Dunedin, a large and competent sprawling state school for boys founded during the royal jubilee of 1935. We wore dark blue shorts and grey pullovers. I still had a funny English accent, and probably as a result of my consequent self-consciousness in speech I developed a bit of a stammer. I soon grew ungainly and spotty as well as inarticulate. I suppose I managed well enough but medieval manuscripts were always my secret escape from a world view seemingly dominated by raucousness and rugby. History was taught, but not very seriously. We did French and Latin. I also took a year of German, which was not available at King’s High, and so we had to troop across to the neighboring girls’ school, called Queen’s High, which made German the most over-subscribed subject in our class.

I recall puzzling over Reed MS 5 at the Dunedin Public Library. It was a very stained and damaged Book of Hours made for a household in the Midlands in 15th-century England. There was a long prayer in Latin on folio 87r including the words “Deprecor te domine. . .per illam pacem quam confirmasti inter angelos et homines fac pacem inter me Margeriam Fitzherbert et omnes inimicos meos. . . .” and so on, and I remember piecing it together word by word with my school Latin dictionary, “I beseech you, Lord”—that is easy—”by that peace which. . . .” and then there was a word which looked like “confinasti,” which I was unable to find until I noticed a little mark over it which must be the ‘ir’ abbreviation over an ‘m’ (not ‘in’) and suddenly there was ‘that peace which you confirmed between angels and men”—imagine a 15-year-old in Dunedin reading this when “peace’ was the buzzword of our Vietnam generation—”make peace between me. . .”—look!—”Margery FitzHerbert and all my enemies. . . .” a real name leaping out of the page, almost certainly until that moment unseen in the manuscript and unread by any single person since the Wars of the Roses, into which, as I soon discovered from encyclopedias, the FitzHerbert family of Derbyshire were reluctantly inveigled. I learned two things that day. I enjoy making discoveries; and manuscripts can talk.

I do not really know what my family thought of my schoolboy obsession with medieval books. They tolerated it as harmless if rather pointless, I suppose. My elder brother used to accompany me sometimes, initially bemused, but he drifted into photography and eventually into journalism. In time, the younger siblings became involved with early computers, natural history and law.

When I was 16, 1 brother and I were sent back to England for 6 weeks to spend Christmas with our aunts and cousins in Wiltshire, and the experience decided my life. First of all, I realized that we talked like everyone else. More importantly, we saw world-famous manuscripts displayed in the British Museum, such as the Codex Sinaiticus and the Lindisfarne Gospels. There was also at that moment a special loan exhibition there from the Dead Sea Scrolls. It was inexpressibly exciting. We were taken to Oxford in the snow and looked at displays in the Bodleian Library, including the great 13th-century Bible Moralisée, and we saw the Alfred Jewel exhibited in the Ashmolean, which impressed us both greatly. We were shown the Magna Carta in Salisbury Cathedral.

I learned two things that day. I enjoy making discoveries; and manuscripts can talk.

It was all a revelation for me. These were manuscripts of an importance infinitely beyond anything in Dunedin, but I realized too that in England a 13-year-old would never have been allowed to open the cases to touch them and to take them home on the bus. The distance of New Zealand from medieval Europe was both a disadvantage and a benefit, and I will still fiercely defend the importance of keeping medieval manuscripts in remote libraries of the world.

__________________________________

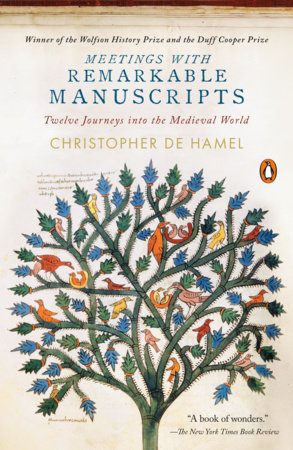

Excerpted from Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts by Christopher de Hamel. A version of this piece first appeared in a special UK edition of Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, published by Allen Lane for Waterstones. Reprinted with permission from Penguin.

Christopher de Hamel

In the course of a long career at Sotheby’s Christopher de Hamel has probably handled and catalogued more illuminated manuscripts and over a wider range than any person alive. Since 2000, he has been Fellow and Librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The Parker Library, in his care, includes many of the earliest manuscripts in English language and history. He is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Historical Society.