Fighting Abroad and At Home: Remembering the Experiences of Black Vietnam Veterans

Wil Haygood on the Long History of Black Heroism and Service—and the Current Efforts to Erase It

If you were a twelve-year-old kid, as I was in the summer of 1966, N. Fifth Street in Columbus, Ohio seemed a bucolic place. Every neighborhood kid seemed to have a bicycle. Trees shaded homes. Men went to work in nearby factories. I didn’t yet know of death. No one close to me had ever died. Skip Dunn lived across the street from me. He was a star athlete in the neighborhood. I was always waving at Skip, who was in high school. “Hey Skip!” And he always waved back. Then one day Skip was gone. Off to a faraway place I saw glimpses of on our television—Vietnam. Skip had joined the Marines.

It was the oddest thing that within thirty yards of my house, six Black teens had gone off to Vietnam. Three lived on my very block; three others on the next block over. I knew them all: Jimmy and Charles Bolden, Steve Collins, Larry Wilson, Robert Morris and Skip. I tossed horseshoes beside them during summers at the local playground. I delivered newspapers to each of their homes. But then war came. Five of the six made it back from Vietnam. Robert Morris was the sole casualty.

Nothing compared to Vietnam when showcasing Black bravery, strength, and even political expression in the war zones of Southeast Asia.

The high number of Blacks going off to Vietnam from my neighborhood can’t really be called a coincidence: In the early years of Vietnam, proportionately more Blacks than whites were being drafted into the war. The draft boards were more than 95% white. Those numerical dynamics made the administration of President Johnson nervous. The war coincided with the civil rights movement and the push for Black freedoms. Vietnam was inextricably linked to a wrenching era in American history, as Blacks were being compelled to fight a war on two fronts—for equality at home and a nation’s hubris abroad.

For the past four years I’ve traveled the country, sitting with Black veterans who fought in Vietnam and returned home to a nation on fire. White America was resistant in many places to integration and equality. Urban uprisings and rebellions by Blacks stretched from coast to coast. I remember sitting around the television watching scenes of street mayhem on the nightly news. My mom and grandparents, who I lived with, hailed from Selma, Alabama. Selma was on its way to becoming Selma. Always, amidst civil rights news, there was footage of Vietnam.

There has long existed in America a conundrum of Blacks and the military, and it stretches back across two centuries. A nation that had enslaved Blacks would come to call upon them during the Civil War to save America. Those Black soldiers—told by Confederate forces they’d be hanged if captured—served with distinction. “We have seen white men betray the flag and fight to kill the Union; but in all that long, dreary war we never saw a traitor in a black skin,” presidential candidate James A. Garfield, referring to the Civil War, said during an 1880 address in New York City.

In World War I military leaders dismissed the idea of Blacks fighting alongside whites. Patriotic Black Americans went to Europe and joined forces with the French to battle on behalf of Democracy. In World War II Blacks fought—when given the chance—and flew planes as Tuskegee Airmen to show their mettle. But nothing compared to Vietnam when showcasing Black bravery, strength, and even political expression in the war zones of Southeast Asia. On some military bases Confederate flags were visible. Black and white interactions—each coming out of segregated environments—could at times prove a combustible brew for military officers. Vietnam introduced America’s first racially-integrated fighting force. “Vietnam was the first time this country had witnessed troops led by African Americans,” as Lloyd Austin, the nation’s first Black Secretary of Defense, and who had older relatives who fought in Vietnam, told me during an interview in his Pentagon office.

Recent American presidents—George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden—have righted grievous wrongs when it came to Black heroes from various wars who were denied recognition and medals by their military branches. These bipartisan salutes have been praised nationwide. That sentiment changed, however, with the election of President Donald Trump and confirmation of Pete Hegseth, his Secretary of Defense. Both seemed hellbent on denigrating Black military achievements and glory, even bizarrely trying to have narratives of Black heroism erased.

The facts of the crucial roles Blacks have played in keeping America united—barely as it may be—through so many wars cannot be dismissed.

First Charles Q. Brown, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a Black man, was fired. Then photos and displays of Black achievement throughout military history that had been on view in forts and military installations were largely removed. Books highlighting stories of Blacks in the military were disparaged, and many removed from the US Naval Academy in what was shocking to military personnel far and wide. The purging became a dangerous echo of McCarthyism, what the Trump-Hegseth forces called their attack against DEI awareness—diversity, equity, and inclusion. The achievements of women also came under attack.

Yet there was little doubt that the Trump administration’s moves seemed particularly—and aggressively—aimed at Black military history. Not since the administration of President Woodrow Wilson, an avowed segregationist, has there been such an all-out assault upon Black excellence across the American military.

What both Trump and Hegseth lack is a sense and appreciation of America’s true military history.

By 1863 the Civil War had been going on for two years. The very continued existence of America as a nation was in jeopardy. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, pleaded with President Lincoln to allow Blacks to be able to join the Union. “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket and there is no power,” Douglass said, “on the earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.” Historians have long made note of the contributions of Blacks in the Civil War.

In 1963—one hundred years removed from 1863—the Black man was in another war, this time in Vietnam. And still fighting for full equality.

There were so many stories I came across while researching my book. While in Virginia sitting with Art Gregg, a retired Army general who served in both Korea and Vietnam, we got to talking about Fred Cherry, also a native Virginian. In his youth Fred Cherry dreamed of becoming a pilot. He joined a segregated U.S. Air Force and distinguished himself during flight training. He eventually flew many missions in Korea. Then it was off to Vietnam, where, in 1965, he was shot down. He became the first Black Air Force officer to be taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese. For years he was tortured, and finally released in 1973.

One evening, back in his native Virginia, Cherry was feted at a gathering. “I am an American fighting man and I wear this uniform to protect you and your way of life,” he said to the audience. “I would have given my life if necessary, proudly and honorably. I was tortured severely. I was severely ill, but they never broke me. They didn’t because I had faith in God, in my country—and in you. If necessary, I will do the same thing again because I want America to be what you want it to be.”

This well might be the season of twisting history, but the facts of the crucial roles Blacks have played in keeping America united—barely as it may be—through so many wars cannot be dismissed.

__________________________________

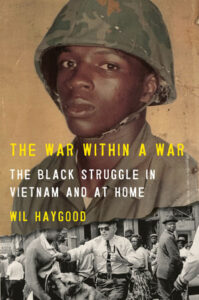

The War Within a War: The Black Struggle in Vietnam and at Home by Wil Haygood is available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Wil Haygood

Wil Haygood is the author of Tigerland, which was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize; Showdown, a finalist for an NAACP Image Award; In Black and White; and The Butler, which was made into a film directed by Lee Daniels. He has been a correspondent for The Washington Post and The Boston Globe, where he was a Pulitzer finalist. Haygood is a Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow, and is currently Boadway Visiting Distinguished Scholar at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.