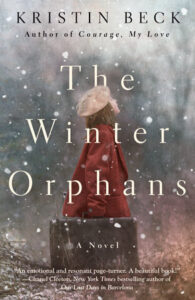

Fictionalizing the Stories of Two Women Who Fought to Save Jewish Children in World War II-Era Europe

Kristin Beck on the Women Who Inspired Her Novel

Rösli Näf and Anne-Marie Piguet were two women who fought to save lives during World War II. As volunteers with the Swiss Red Cross in occupied France, Rösli and Anne-Marie cared for approximately one hundred Jewish refugee children in a derelict château, offering them a sense of safe harbor in an upturned world. However, when danger arrived on the château’s doorstep in 1942, Rösli leapt into action and vowed to do whatever was necessary to protect her charges. This became seemingly impossible as the war raged on, yet Anne-Marie readily joined the mission, ultimately guiding imperiled youth to safety over wild, wintry borders. My novel, The Winter Orphans, explores the contributions of these two women.

From the moment I encountered Rösli and Anne-Marie, I was spellbound by their courage in the face of harrowing circumstances and, later on, their humility. Near the end of her life, Rösli, in particular, shrugged off accolades for her actions and turned away from the spotlight. Upon learning this, I realized that I wanted Rösli and Anne-Marie to play a role in my next novel, and I set off to discover who they really were.

Rösli Näf was born in Glarus, Switzerland, and despite humble beginnings she was determined to pursue an education. She also yearned to see the world, so she studied nursing and spent her early career working in Lambaréné, Gabon in a hospital run by the famous Dr. Albert Schweitzer. It seems that she found this position to be quite challenging until she took over the hospital’s gardening program. There she not only thrived, but acquired skills that would later serve her well in occupied France. After three years in Africa, Rösli returned home. In 1941 she took a position as director of a Swiss Red Cross children’s colony at Château de la Hille, and she moved to Vichy France.

Survivors of La Hille remembered Rösli as a somewhat stern, difficult personality. In a moving memoir, Inge, a Girl’s Journey through Nazi Europe by Inge Joseph Bleier and David E. Gumpert, Rösli is shown struggling to relate to the teenagers under her care. Bleier recalls episodes of tension and even confrontation between the young Red Cross director and her charges, which seemed to arise from Rösli’s inflexible leadership and general lack of social aptitude. Similar memories surfaced in other works by survivors and their family members, including Muriel R. Gillick’s Once They Had a Country, and Walter Reed’s The Children of La Hille. Indeed, in everything written concerning Rösli Näf, people who knew her recalled her as socially awkward at best.

She may have been an exacting and difficult leader, yet in the face of staggering danger Rösli readily stepped in to protect the children of La Hille.

And yet, when the Nazis and their French collaborators threatened the children under her care, Rösli devoted herself to saving them against all odds. This, too, was remembered by all who knew her in France. When the police came for the children of La Hille, Rösli created hiding places, sought legal routes out of the country and, when that failed, forged illegal passages. She may have been an exacting and difficult leader, yet in the face of staggering danger Rösli readily stepped in to protect the children of La Hille.

After the war, Rösli dipped into obscurity. Details about the remainder of her life are sparse, other than the fact that she moved to Denmark to live on a collective farm, choosing to reside there because she admired the way Danes had largely saved their Jewish neighbors from Nazi persecution. At the end of her life, Rösli returned to Glarus, Switzerland. Prior to her death in 1996, she told a journalist that she only regretted not saving more children.

Anne-Marie was another person who was uniquely suited to the task of saving people in peril. As is recounted in her memoir, La Filière en France Occupée 1942-1944, Anne-Marie’s grandfather and father were both foresters in the Risoud, the largest forest in Europe. Draping the border of France and Switzerland, the Risoud comprised the playground of Anne-Marie’s childhood, and she grew up hiking its many paths. She likely never guessed how valuable her knowledge of those wooded mountains would become.

As a young woman, Anne-Marie studied literature in Lausanne, earning her degree before volunteering to work with the Swiss Red Cross in France in 1942. In addition to her memoir, I was able to access videos of Anne-Marie as an elderly woman speaking about her wartime experiences; her personality shines through in these interviews, which influenced my depiction of her in The Winter Orphans. The true Anne-Marie appears warm and quick to laugh, thus it was easy to imagine her as a joyful and loving caretaker of refugee children. However, this easy-going nature is balanced by the incredible strength she displayed later, when the children were threatened, and she risked her own life to save them.

After the war, Anne-Marie not only married and established a family, but she also spent the rest of her life involved in humanitarian activities. Notably, in 1956 she co-founded an organization called the Swisscontact Foundation, which still supports economic, social, and ecological development in emerging economies across the world. She was formally recognized numerous times for her work involving human rights, including winning the Doron Prize which honors Swiss citizens for significant charitable endeavors.

In 1991, Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, recognized Anne-Marie Piguet as Righteous Among the Nations for her efforts to save the lives of Jewish people during the war. Yad Vashem also sought to honor Rösli in 1989, but she initially declined her medal. She didn’t relent until 1992, when a ceremony was held for two of her colleagues and she finally accepted hers. I imagine that Rösli shrank from recognition because she believed praise wasn’t required for doing what was so obviously morally right. Indeed, all her life she only wished she could have done more.

This poignant humility is what initially drew me to Rösli, though I’ve long been captivated by women’s experiences during World War II. My fascination began with own grandmother’s stories. As an army nurse stationed in England, she traveled to France in the wake of D-Day. There, she worked in muddy field hospitals near the booming front, caring for men injured in the battle of Normandy. As the fighting moved north, she followed the Canadian army to Belgium, setting up medical posts in bombed buildings, triaging the wounded, and serving on hospital trains snaking through explosive nights.

Though my grandmother’s story is fundamentally different from Rösli’s and Anne-Marie’s, I recognize commonalities among them. My grandmother was matter-of-fact when she shared her wartime memories, reacting to any surprise or admiration with bemusement. Like the heroines of my novel, she was modest regarding her astounding bravery. When challenges arose, for both my grandmother and the women of La Hille, they were simply met. These are women who did what needed to be done, despite great adversity and personal danger, and expected little recognition for their contributions later in life.

It is my honor to shine a light on such contributions now. The Winter Orphans is a tale of dangerous times and unthinkable tragedy, yet it’s burnished with hope. In Rösli, Anne-Marie, and the children they saved, we find people who unwaveringly met evil with goodness and challenge with determination. Set in an era of great inhumanity, this is, ultimately, a story of love. May its readers find this tale of real-life heroes to be as captivating and affirming as I did.

*

Works Cited:

Bleier, Inge Joseph, and David E. Gumpert. Inge, a Girl’s Journey through Nazi Europe. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004.

Gillick, Muriel R. Once They Had a Country, Two Teenage Refugees in the Second World War. The University of Alabama Press, 2010.

Im Hof-Piguet, Anne-Marie. La Filière en France Occupée 1942-1944. Éditions de la Thièle, 2019.

Reed, Walter W. The Children of La Hille, Eluding Nazi Capture during World War II. Syracuse University Press, 2015.

____________________________________

Kristin Beck’s The Winter Orphans is available now via Berkley.

Kristin Beck

Kristin Beck first learned about World War II from her grandmother, who served as a Canadian army nurse, fell in love with an American soldier in Belgium, and married him shortly after VE Day. Kristin thus grew up hearing stories about the war, and has been captivated by the often unsung roles of women in history ever since. A former teacher, she holds a Bachelor of Arts in English from the University of Washington and a Master’s in Teaching from Western Washington University. Kristin lives in the Pacific Northwest with her husband and children. The Winter Orphans is her first novel.