Feral, Beautiful and Free: Sarah Cypher on Turkish Cats

Also, They’re Not Actually Agents of the Devil

On a cliff above the Mediterranean, another Antalya cat watches sunlight touch the eastern slopes. She’s a dusty old queen perched a hundred feet above blue water, overlooking the sunrise on the Taurus Mountains. It’s my first visit to Turkey—or Türkiye, since its April 2022 name change. Its unofficial designation, however, is as a byway in the worldwide cat reverence zone.

I admit to a weakness for feline charisma, but here, the cats’ charm and extroversion are uncanny. By comparison, my fickle floof at home merely tolerates the dog and her delight can only be coaxed out with ice cream and the smell of a fresh cardboard box.

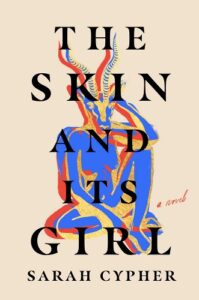

A few years ago, I traveled to do research in the West Bank, where my novel The Skin and Its Girl is partly set; it’s about the queer women of a Palestinian soap-making dynasty, and one of the soap factories bears my maternal family’s surname. But while there, I also saw my grandfather’s gravelly affection for cats magnified across entire cities. Not since that trip have I felt such comfort in the sight of so many cats luxuriating on two-thousand-year-old stonework, and, as I make my way around the country now, one peers out of a courtyard built before the Roman Empire fell.

In the cat reverence zone, they’re part of the public trust: cats-in-common, free agents with favorite people and favorite hangouts.

Walking through Karaalioglu Park, for instance, I see a sinewy flash of calico fur, then a jet-black catloaf napping on the seat of a parked motorcycle, then a smoke-gray adolescent sprawled on an empty park bench, cleaning his paws al fresco. Istanbul contains a quarter of the nation’s human population and, at best guess by the city’s municipal veterinarians, a few hundred thousand cats (and an equal number of roaming dogs). A 2004 law created a budget for animal healthcare, and a related sterilization effort keeps the population stable.

Here in Antalya, the smallest kittens dash into hedges and climb the tablecloth at the seafood restaurant, looking barely beyond weaning. I’ve had my flights booked for longer than these kittens have been alive, and they are already savvier than I about dodging cars, which speed through the narrow streets of Kaleiçi, Antalya’s old city, so boldly that they too must have whiskers for navigation. Smitten, I snap so many pictures on my phone that my friend challenges me to find the difference between my almost-frantic collecting of cute cats and his playing of Pokémon Go. (“I might eventually get paid?” I say.)

To call them all street cats wouldn’t be fair. In the cat reverence zone, they’re part of the public trust: cats-in-common, free agents with favorite people and favorite hangouts. Take the one at Sedir, a barbecue restaurant a mile off the main tourist drag in Konyaaltı Beach—she’s curvy and persuasive. By the time the esme is gone and the döner and şiş are on the table, she’s already pegged us for marks, clawing the chair, appearing in the planter beside the table, and then receiving several shreds of my dinner as a tribute. “To waste food is a sin,” says our friend Kadir, “so it is better to feed the remainings to them.”

Walking home late at night, I see little piles of chicken on the pavement, dismantled by the kitchen staff into a feline offering. During mealtimes, it is more typical to see diners meet encroachments with good-natured exasperation—a man sweeps his bread back from the edge of the table and roughly caresses the head of a speckled orange tomcat. Some get chased off with a napkin or a foot, or are lucky enough to be carried by a busboy to the end of the alleyway with a kiss between the ears.

It’s easy to romanticize such a kind-hearted engagement of humans with animals and the degree to which everyone seems to be observing the same interspecies treaty. But the area has a long history of respecting cats for their service to human health: what I haven’t seen are rodents of any kind. In fact, even during the centuries when Constantinople was still a Christian city, it broke with the rest of medieval Europe’s view on cats, declining to exterminate them as agents of the devil, and thus having an extra line of defense against the bubonic plague. Islam had taken a different view from the start: cats are regarded as holy and ritually clean (e.g., Sunan al-Tirmidhī 92).

You can deduce this even if you haven’t grown up Muslim or learned the Hadith; simply judge by the worshippers’ indifference to the entrance of a bolting cat in a mosque, or by Gli the cross-eyed Hagia Sophia cat, who has their own Tumblr page. But the cat reverence zone predates Islam by at least 1,400 years: in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums is a terracotta cat sculpture dating back almost to 900 BCE, from the island of Rhodes. From ancient days to the digital present, they are a touchpoint for a uniquely human sort of empathy: “They are fed and given water,” Kadir says, “because we never know when we might be in their position, outside with nothing to eat or drink.”

Cats rule their urban ecosystem, but as in all contemporary human population centers, they only rule as deputies among our resorts and roadway.

To be fair, not everyone melts for a cat, and the dog-loving part of my heart pangs when regarding Turkish dogs’ aloofness. Though they don’t appear to be any hungrier or more ragged than their feline counterparts, they do seem less beloved, more stray. Also, there are precious few birds in Antalya smaller than a pigeon. Cats rule their urban ecosystem, but as in all contemporary human population centers, they only rule as deputies among our resorts and roadways, our plastic litter and commercial strips.

Their position is only as secure as humans allow it to be. Political and cultural whims hurt them—as today, with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s intent to clear the dogs into dangerous shelters and his rhetorical jabs at pet owners, who trend more moderate than his conservative, populist base. Exterminations at the turn of the twentieth century sought to make the cities appear more Western, and poisoning the stray and feral animals persisted into the 1990s, before the protective 2004 law.

In English, the word feral leans negative, yet it has human fingerprints all over it, bearing, as it does, the implication that obedience is a possibility, and less overtly, that the creature still depends on us. But throughout Türkiye, Palestine, and other areas of the cat reverence zone, popular empathy for cats prompts a wider imagining of what we might accomplish with our tolerance and generosity toward those who need it, and how these virtues dignify us.

At the hotel curb as my wife and I prepare to depart Antalya, a streaky, gray-and-black tabby leaves the hedge, carves a single soft S around the ankles of a woman unloading her belongings from the back of a taxi, and cozies into her canvas carry-on. The cat is pleased, the woman is happy, and the handful of us other tourists coo our amusement at the situation in a language that seems not only universal but timeless.

__________________________________

The Skin and Its Girl by Sarah Cypher is available from Ballantine Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Sarah Cypher

Sarah Cypher has an MFA from the Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College, where she was a Rona Jaffe Fellow in fiction, and a BA from Carnegie Mellon University. Her debut novel The Skin and Its Girl was a Stonewall Honor Book. Her writing has appeared in the New Ohio Review, North American Review, and Crab Orchard Review, among other publications. She is from a Lebanese Christian family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and lives in Austin, Texas, with her wife.