Feather By Feather: On Life, Death, and Birding

“I don’t know if I believe in signs. But in that moment, I needed one.”

A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird.

It’d been raining that day: the world outside had been coated in a wet, pewter varnish, muted and hollow. My mother and I sat on the couch in a stunned stillness, each cradling a mug of chamomile tea we weren’t really drinking. Everyone who’d come to the funeral had left the night before. Now it was just us, trying to make sense of the quiet.

We were mid-sentence—trivial talk, the kind you resort to when anything real feels too sharp to touch—when a red-tailed hawk cut through the gray and landed on our deck railing. Five feet from us. Close enough that we could see the rain slicking its feathers, the slow expansion of its rib cage as it breathed.

We lived in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Red-tailed hawks were common. You saw them on fence posts, in the far corners of fields, circling above highways. But not like this. Not at eye level. Not watching us as if we were the ones who’d appeared suddenly in its world.

I don’t know if I believe in signs. But in that moment, I needed one.

“Mom,” I said, my voice trembling, caught between disbelief and laughter. “Look.”

My brother had loved birds; he’d kept a cockatiel named Gus who’d cat-call people as they walked by. And for years, I’d pester him with the same questions: If you could be any animal, which would you be? If you could have any pet—no rules, no laws—what would you choose? If you were reborn, what form would you take?

There was only ever one answer.

I was an aspiring writer in my mid-twenties then, my first novel unwritten. But I’d write bits of funny dialogue I’d overheard, or interesting news stories, in case they’d generate ideas. I wanted to believe that life itself was offering clues, if I could just learn how to read them.

And now a red-tailed hawk was staring back at me.

Part of me wanted to rationalize it away. To tell myself it was a bird, resting where it pleased. A coincidence, nothing more.

I don’t know if I believe in signs.

But in that moment, I needed one.

That was eight years ago.

*

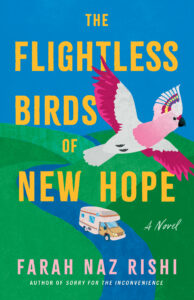

My fifth book, The Flightless Birds of New Hope, is about birds.

On the surface, it’s about bird competitions—wholly fictional, slightly absurd—and a couple, Aliyah and Jay Shah, whose lives revolve about their prize-winning cockatoo, Coco Chanel. But the story truly begins when Aliyah and Jay die unexpectedly, leaving their three children behind. Not just to navigate their grief, but to care for the bird that shaped so much of their family’s identity.

I’ve always liked birds, the way one likes cool water on a hot day, or breathing. Birds were a comforting but unremarkable part of the world’s backdrop.

After my brother died, though, that changed.

I couldn’t stop seeing them. Pigeons waiting at street corners for a crumb. Sparrows hovering by our window. Starlings watching our dog at the park.

At night, I would cry until my throat hurt, telling Stephen, the man who would become my husband, that I felt like I no longer belonged anywhere. My brother was gone. The year before, my dad had died; later, my mother, taken by illness. Home had become a memory instead of a place.

I was molting. Shedding pieces of myself that once felt permanent. Grief had stripped me down to something raw and featherless. I didn’t recognize what remained.

Then one day, an idea surfaced: What if I wrote about birds and siblings? About losing family, and finding them again? About migration as something emotional as much as physical?

It felt ridiculous. I read and wrote rom-coms, mostly. A story about a talking bird with PTSD felt wildly out of my wheelhouse. Maybe it was a symptom of my new depression medication.

Maybe sometimes, a bird is just a bird.

But not long after, I was walking through Philadelphia when I saw an older man sitting on a bench with a cockatoo, perched calmly on his shoulder. He smiled at the bird, like they were old friends. Like the world was theirs alone.

Despite myself, the idea returned.

For a moment, I let myself believe this encounter meant something. That maybe all these birds were breadcrumbs leading somewhere. After all, that’s what grief does: it leaves you with an empty, starving void. Not just for the person who is gone, but for assurance that your pain is part of something bigger than yourself.

Or maybe it was nothing. Maybe sometimes, a bird is just a bird. Metaphors wouldn’t bring my brother back.

But even as I tried to dismiss it, something in me had shifted, quietly, almost imperceptibly. A small part of me was already writing.

And I found myself wondering, not whether my grief would disappear, but whether one day I might be able to carry it with the same calm certainty he carried that cockatoo.

A few weeks later, I started writing the book. And the story arrived the way storms do: without permission, without warning. Without asking whether I was ready.

In The Flightless Birds of New Hope, Aden—the eldest child and central character—releases the cockatoo Coco in an alcohol-fueled rage. He blames her for everything he lost: his childhood, his parents, the safety he should have had. His parents were consumed by their obsession, and when the pressure became unbearable, Aden ran, abandoning his younger siblings, Aliza and Sammy, in the process.

When Aliza discovers Coco is missing, she refuses to let grief fracture their family further. She forces Aden to come with her on a mad search. Meanwhile, Coco keeps flying west, as if following a map no one else can read.

Because here’s the truth no one wants to say aloud: grief doesn’t resolve.

Writing this book let me rehearse the conversations I will never have. Aden and his siblings get to say the things I cannot. I could return to places I can no longer go, ask the questions life refused to answer. Those haunting questions: what’s the point of it all. Does anything matter. Can God hate his own creations the same way I scowl at my manuscripts.

Aden believes life is senseless, arbitrary. And sometimes, especially in the darkest moments of writing, I feared he was right.

Writing the book didn’t give me answers; I’d written a memoir the year before, and even that didn’t feel enough. It didn’t make my grief feel noble or purposeful, and it didn’t return what was lost. But it did give me space—an interior wilderness vast enough to hold both the absurdity and the ache.

Because here’s the truth no one wants to say aloud: grief doesn’t resolve. It isn’t like a bout of the flu.

Instead, it changes shape. Some days it is a knife. Some days it is a ghost. Some days it is simply background noise—the hum of an appliance, the distant traffic. Bird song.

But it never disappears.

Still, we go on. We molt. Maybe that’s the closest thing to meaning we get—not revelation, or redemption, but the refusal to stop becoming.

If meaning exists, we build it feather by feather.

Sometimes I think about that hawk on the railing—the way it watched us through the rain, unblinking and steady. I no longer try to decide whether it was a sign or a coincidence, whether it meant nothing, or everything. I don’t need the hawk to be my brother for the moment to matter.

Maybe it was just a hawk. Maybe it was simply a reminder—feathered and ordinary—that life continues, even in the wreckage.

What I do know is this: I saw it. I thought of my brother, my grief.

That, I think, must count for something.

__________________________________

The Flightless Birds of New Hope by Farah Naz Rishi is available via Lake Union Publishing.

Farah Naz Rishi

Farah Naz Rishi is a Pakistani-American Muslim writer and voice actor, but in another life, she’s worked stints as a lawyer, a video game journalist, and an editorial assistant. She received her B.A. in English from Bryn Mawr College, her J.D. from Lewis & Clark Law School, and her love of weaving stories from the Odyssey Writing Workshop. When she’s not writing, she’s probably hanging out with video game characters. You can find her at home in Philadelphia, or on Twitter at @farahnazrishi.