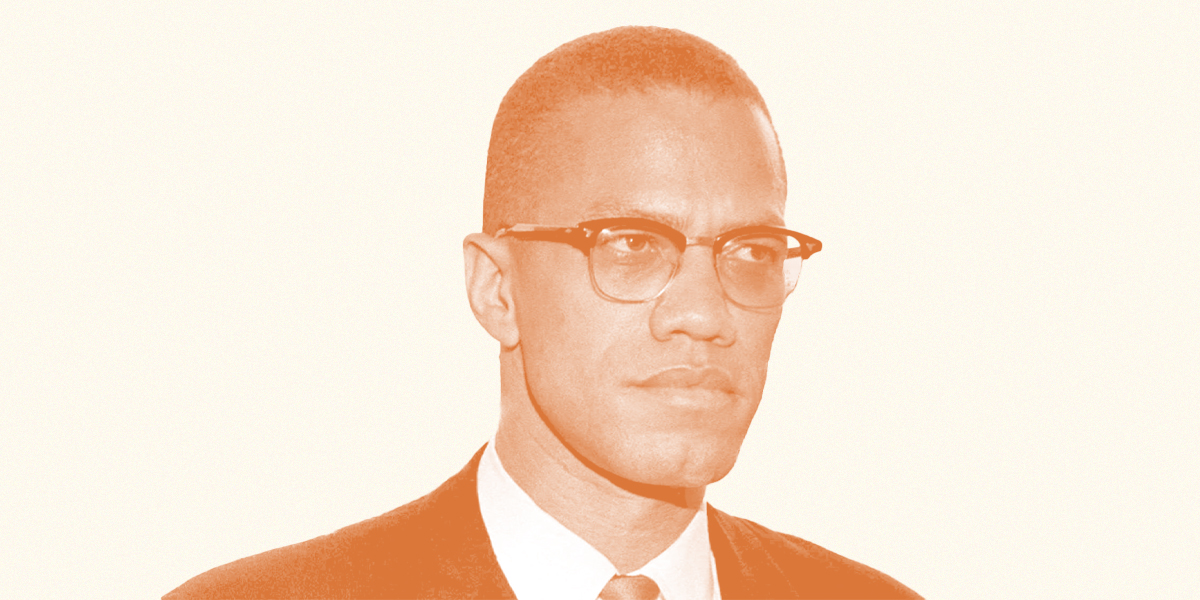

Fatima Bhutto on Channeling the Fearlessness of Malcolm X

“I learned how to be lonely from a young age.”

In June 2020 Dennis Dalton, 82 years old, stood in Pioneer Square in downtown Portland and raised his right hand in the air. “This hand shook the hand of both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King,” Dalton told the assembled crowd of African American pastors and protestors. It was the first time Dalton and his wife, Sharron, had been outside in the three months since lockdown. Their son had brought them groceries and handed them over; no one hugged anyone. No exceptions had been made; no one broke social distancing. Though Dalton had begun his life of protest marching for civil rights on the fringes of the Montgomery bus boycotts, taking to the streets against the war in Vietnam and America’s myriad other occupations and invasions, and most recently in support of Occupy, he hadn’t gone out this time. There was a pandemic going on and Dalton was asthmatic.

“You know I’ve given my life to studying Gandhi, more than Malcolm, more than King,” Dalton tells me over Zoom later. “And Gandhi’s greatness was, during Partition and during the last five months of his life, he made a series of speeches at his prayer meetings calling on the Hindu majority community to defend the Muslim minority community. He said at the time, you imagine you have human rights, but your rights are real only if you perform the duty, the obligation you face, and that duty is to protect the minority.”

Dalton is retired and now teaches classes on ethics and philosophy to students at a Portland public high school. It was in one of his online classes during lockdown that he was confronted with a student, a high-school senior, who told him she’d been tear-gassed by police at a protest and injured. “I couldn’t sit back and watch my own student be persecuted on the streets,” Dalton recalls. “I joined the protests at that moment.”

“That day?” I ask, unsure.

“No, that moment.”

*

I first met Professor Dennis Dalton 19 years ago, when he taught me political theory at Barnard College. We were studying Lao Tzu on the day 9/11 happened, after the towers fell and before Columbia University was closed down for the day and SWAT teams placed on our roofs. He taught us Plato, John Locke, Thoreau. In Political Theory II we studied Gandhi, Malcolm X and Emma Goldman, the Jewish anarchist and political activist. He showed us clips from A Bronx Tale to illustrate Machiavelli. He invited members of the nearby Harlem community to audit his classes for free; one of the elderly students who came was a lieutenant of Malcolm’s, who had been with him when he was killed in the Audubon Ballroom on February 21, 1965.

At the beginning of each semester, Professor Dalton handed out a sheet we had to sign and return, promising we would not grow up to be lawyers. When his beloved granddaughter, then a young child, was bitten by the family dog—who was until then docile—Dalton stood in front of our class in tears and told us that though his granddaughter’s ear had been torn, nearly ripped fully from her face, and the family was considering putting the dog down, he could not support them. He didn’t believe in violence. No harm would come from his hands to another being, no matter what they had done. The dog was saved.

“You have human rights, but your rights are real only if you perform the duty, the obligation you face, and that duty is to protect the minority.”

Dalton would end up being my thesis adviser; the friends I made in his class were a devoted set of disciples—all of us sitting in the first row, staying afterwards for the discussions Dalton convened twice a week, turning up at his office hours to ask one more question. We came together, and to Dalton, because we were in pain. A pain that he recognized and illuminated before soothing, speaking to us of other worlds in which it was possible to be freed from our anxieties.

It was during our finals for Political Theory II that I was struck by a vicious panic attack that began a frightened season in my life. I had studied hard for the exam and knew I would do well, but when my hands started shaking and my heart thrashed against my chest, I looked up at Professor Dalton and wondered if he would understand if I were to throw my blue exam booklet to the floor and run out of the classroom crying. He would understand, I thought, but I didn’t want to let him down. I stayed and finished the exam even as the panic flooded warmly though my body and convinced me I was dying.

Professor Dalton was a guide and mentor during an uncertain time, and he changed my life and thinking in many ways. But it was Malcolm X and the study of his life and journey that affected me most deeply. Malcolm X, who, as James Baldwin said, knew that the Western world’s relationship to us, all us non-whites, was one of plunder. Malcolm, who suffered violence from childhood, losing his father—murdered by white supremacists when he was just six years old, the age my own brother was when our father was killed in Pakistan. Malcolm, who dreamed of becoming a lawyer when he was a boy and was told no, Black boys couldn’t be lawyers. Why didn’t he—the smartest boy in the classroom—become a carpenter, his teacher suggested, why not work with his hands instead?

I love Malcolm for his truth and beauty. When asked, after leaving the Nation of Islam, what qualified him to be an independent political leader of any sort, Malcolm replied, “I am not educated, nor am I an expert in any particular field. But I am sincere, and my sincerity is my credential.” Malcolm, who said to James Baldwin—another man I love for his deep truth and beauty—”I’m the warrior of this revolution and you’re the poet.” As the protests swelled across the world in summer 2020, I found myself thinking back in time, to my professor who brought Malcolm X to life in a college auditorium week after week. Where else could we travel during a global quarantine but the past?

*

I should have been fine in lockdown. I’ve spent a great amount of life under some kind of quarantine, after all. After my father, a member of Parliament, was killed, I couldn’t go anywhere except to school and back, shadowed by two trucks of armed Pakistan Rangers, a federal paramilitary organization that the government insisted was there for my safety. I was 14 years old. If I wanted to go to a friend’s house, I had to give the Rangers plenty of notice so they could travel ahead to do a security check of the location. If the location was secure, the Rangers would surround the house, their Heckler & Koch automatic rifles in their hands, standing at the ready. I was allowed out for only two hours at a time, but given the scene the Rangers and I caused, I rarely went anywhere. My father had been killed by the state and now the state wanted to protect me. I learned how to be lonely from a young age. I had dogs and a telephone. I read, I wrote, I sat in solitude.

I have been preparing for this moment my whole life. Whether I’m going away for three days or a month, I take everything with me, in case I never come back. I have whittled down my shoulder bones carrying heavy bags, transporting my life back and forth across cities for years. This is how we’ll have to live in a world of pandemics and lockdowns, moving hesitantly over a terrain of endless uncertainty. I should feel pleased to have had all this preparation and practice, but I don’t.

My father had been killed by the state and now the state wanted to protect me. I learned how to be lonely from a young age.

In my adult life, I live alone, and loneliness has a different shape. I have a dog and I have my books and telephone and all my portals to the world far beyond my shifting borders, but I’m not the same person any longer. I miss the world. When the globe went into lockdown in March, I thought I would be wildly productive: Reading like in my teenage years! Writing thousands of words a day! Deep reflections and insights to follow! But mainly, I felt quiet and distracted. The acute isolation reminded me of my past. I worried about how I would live without being able to travel, to see people I love, to do all the things I had put off and avoided, thinking I had infinite time. I tried to remember what Susan Sontag said: “Just wait until now becomes then, you’ll see how happy we were,” but day by day, I felt a burning flame flickering down to the halo of blue light just before it fades, vanishing into nothing.

*

In 1961, Dennis Dalton had returned from a year in India as a Fulbright scholar. He was beginning his master’s degree in Indian political thought at the University of Chicago when he heard that Malcolm X would be speaking at a local mosque. He was curious to hear Malcolm, who was already known for his radical stance towards freedom—freedom at any cost, by all means necessary. Dalton was the only white person at the meeting that day. And though he was electrified by Malcolm, by his clear denunciation of the Vietnam War, Dalton had been intimidated by Malcolm’s exclusivist rhetoric. He described white men as the devil and even as his words were carried by the power of their clarity and eloquence, Dalton felt uneasy. “King didn’t have the ferocity of Malcolm,” Dalton tells me, reflecting back to that day. “He certainly had the charisma, he was immensely powerful as an orator, but there was a different chemistry about him. The chemistry of Malcolm was intense, so incredibly personal. King was of another style: aloof, imperial, deeply impressive—his voice was like listening to the angels.”

Uncomfortable as he was, Dalton waited till the event was over and went up to Malcolm afterwards. “I said to him, ‘Malcolm, I am eager to help your movement against white racism in any way that I can.'” He explained that he had recently returned from India and that he was considering returning to the subcontinent with the Peace Corps, which had just been founded. Dalton asked Malcolm X whether he had any advice on how to best use his time effectively with the Peace Corps. Malcolm gave the 23-year-old Dalton a strange look. “You know what Peace Corps means, boy? It means America getting a piece of the country.” Before Dalton could respond, Malcom X continued: “You asked me what you can do for my movement, I’ll tell you: you can do nothing.”

*

The weeks blend into one another and time—already meaningless for a writer—becomes even more so. The arbitrary schedules we cling to with devotion and superstition mean less by the day. When the world is cruel to us, we endure by adapting ourselves to new ideas in order to survive. We persevere. But when life is cruel to others, it is so much harder to bear. What we are living through now seems unbearably cruel: that a minority of us can afford to lock down at home, lazing through the hours or even working from a comfortable desk with our guarantees of food and shelter undisturbed, while more than half the world, if forced to lock down, will starve to death.

Where else could we travel during a global quarantine but the past?

The cruelty of the world comes in infinite sizes; we did not need a pandemic to know this. One summer, I saw a man at a fountain in a public park of a rich European city. He was dressed in jeans and a T-shirt and he ran his wrists and hands through the water, cupping it in his palms and splashing it over his face, rubbing his wet fingers behind his ears. I watched him for a moment, thinking he was a Muslim doing his ablutions. I wanted to see where he was going to pray in the park, but he kept washing and after waiting a moment, I moved on, but as I did so, I saw a toothbrush and a tube of squeezed toothpaste in the back pocket of his jeans. He wasn’t doing his ablutions—he was homeless. He was bathing himself.

In lockdown, I sit at my computer on a desk stacked with books and notepads and wonder, what does any of this matter? My schedules, my writing, my suffocating feelings and assumptions of myself. My imagination that I alone endure daily catastrophes, personal and impersonal.

Nothing, I suspect. It doesn’t matter at all.

*

The second and final time that Professor Dalton met Malcolm X was four years later in 1965, on a rainy day in London. Dalton was working towards a Ph.D. at the School of Oriental and African Studies, where I did my master’s, when Malcolm came to speak at the nearby London School of Economics (LSE). “He was there speaking to end the war in Vietnam,” Dalton tells me. “Malcolm had seen the immorality of the war early on. He immediately opposed it, four years before King. I was drawn to Malcolm still for that reason: because I was intensely opposed to war and was immensely disappointed that King had not opposed it.”

By the time Malcolm and King had been killed, as James Baldwin would write in Esquire, “there was practically no difference between them.” But on that rainy day, small gaps still remained between the great men, and Dalton remembers being moved by Malcolm’s anti-war speech. Once more, he waited till the event had ended and approached Malcolm. “Malcolm,” Dalton intoned in his gravelly voice, “We’ve met before—you won’t remember this—in Chicago. But I want again to offer whatever assistance I can. We are both together in this cause to stop American imperialism abroad”’ Thinking back to that last meeting, Dalton paused. “His demeanor towards me had changed entirely. He reached out his hand and said, ‘Brother, if we can do anything together to stop American colonialism and racism, then we’re together. I’m with you and you’re with me.'”

The world was aflame, Professor Dalton tells me. 1968 was on the horizon and Malcolm anticipated the danger ahead. He was a true prophet; he saw the conflagration coming. “Malcolm was a man who searched for truth.” I watch my professor speaking through the small square of a Zoom window. “And it was a truth attained through immense struggle.” The journey: this is what Dalton taught his students in that university classroom so many years ago. The beauty and the wonder of life is there in the process, in the stumbling and the becoming.

“If Gandhi, killed when he was 78 years old, if he had been killed when he was 39, like Malcolm was, we wouldn’t know Gandhi today.” Dalton shakes his head sadly. Malcolm was moving fast in this period of time. Ten days after his speech at LSE, he would be killed. But then, less than two weeks before he was taken from us, under that rainy English sky, Dalton reminisces, he was magnificent.

*

As lockdown in spring becomes lockdown in summer, as the world feels further and further away, and cruelty and trouble fester, I lose the heart and energy to dial in to other times. But I wonder often about my professor. One day when we speak on Zoom—where his screen name is “Dennis (he/him)”—I ask him about the first day he broke quarantine to join his high-school students in Pioneer Courthouse Square, the day he made that speech about Malcolm.

They were all wearing T-shirts—Dalton’s had a photo of the only meeting between King and Malcolm, on the steps of the Capitol in 1964, where both men had come to listen to a Senate hearing on ending segregation—but the police were out in riot gear. Standing with his teenage students, Dalton joined in the protest call-outs. “There’s no riot here,” they shouted, “Why riot gear?” They stood at the barricades and shouted “Quit your job! Quit your job!” at the police dressed in turtle-shells and helmets.

Professor Dalton extended his hand to a police officer and told him a story about Thoreau. In 1848, when told he would be jailed for the refusal to pay his poll tax in resistance to his country’s war with Mexico and the ugly sanction of slavery, Thoreau replied to the town sheriff, his friend Sam Staples, that jail or not, he would not pay his tax. ‘I have no choice in that case,’ Staples responded. ‘I have to arrest you.”You do have a choice,’ Thoreau reminded his old friend. ‘You could resign your office.’

“And you too,” Professor Dalton said kindly to the police officer, “Also have a choice. You can quit your job.” The police officer was predictably unimpressed. “But Professor Dalton,” I ask, “wouldn’t lawyers have been useful then—at these protests where high-school students are being tear-gassed?” Dalton nods at me through his screen. “Yes, I suppose so.” And then he pauses. “But remember, when Thoreau was arrested, he didn’t say, ‘Call my lawyer.’ When Gandhi was arrested, he never said, ‘Call my lawyer.’ And he was one.”

Portland will become ugly later in the summer. In July, federal agents without insignia, in full camo, their faces covered, will pull protestors from the streets and force them into unmarked vans. I see video footage of stun grenades and tear gas fired into crowds of young people, a flashing of light before the thunder-clap of the grenade. Every time I ask Professor Dalton if he is still going to the protests, he says yes. He is standing at the barricades. He is there on day 45, day 50, day 59. He hasn’t been tear-gassed or beaten, he assures me, but he is not afraid. He doesn’t promise any of us that he will stay home. I think of what Malcolm said of himself: “I live like a man who is dead already.” Malcolm’s beauty is that he was a fearless man. A free man.

Professor Dalton calls on Zoom one evening; it’s early in Portland and he was protesting the night before. He is tired but Sharron, his wife, hands him the sign he was carrying at the protest to show me. “Malcolm urged us ALL to protest Racism,” it reads.

__________________________________

Excerpted from This is How We Come Back Stronger, a collection of essays edited by the Feminist Book Society. Copyright © 2021. Available from Feminist Press.

Fatima Bhutto

Fatima Bhutto was born in Kabul, Afghanistan and grew up between Syria and Pakistan. She is the author of five previous books of fiction and nonfiction. Her debut novel, The Shadow of the Crescent Moon, was long listed for the Bailey's Women's Prize for Fiction and the memoir about her father’s life and assassination, Songs of Blood and Sword, was published to acclaim. Her novel The Runaways is available from Verso.