I woke with the heat and voices of the morning, and looked for Pietro’s foot; sticking mine out into the space, I remembered that I was in the little bed, was alone, and hadn’t yet written to him. My husband and I didn’t like to talk on the phone when we were apart; we’d made a pact not to intrude on each other, to act so that our lives, once they were distant, could take different routes, all possible routes. “Good morning,” I wrote, sleep making my hands sluggish, as I tapped on the phone with half-closed eyes. “Everything fine here, hope so for you.” The lack of a question mark was the signal: You’re not obliged to answer, I know you’re there.

On the street, two floors below, a motorbike with a broken muffler was slowing down, a girl was calling someone in a loud voice, from the balcony opposite came the sound of carpets being beaten in the sun. In the room the light absorbed the excess dust, the outlines of objects became fixed, thoughts returned to order. The memory of insomnia got me up immediately, frightened: it was better not to delay, not to stay imprisoned in bed after such a difficult first night.

I crossed the hall barefoot, in my underpants and the T-shirt I’d slept in. In the kitchen, a sheet of graph paper was stuck in the spout of the coffeepot on the unlit stove, bearing my mother’s prescriptive writing and the imperative of a single word: “Light.” Passing her room, I had glanced in and seen that it was empty, but I didn’t need proof; I knew very well that we were alone, the house and I.

Whenever I stayed alone in an unfamiliar apartment, I moved in a state of paralysis, cautiously obedient, under the severe gaze of the absent owners. If they had told me to take off my shoes, I walked barefoot, if they were afraid that something would break, I didn’t even touch it, as if they really could reproach me for violating their rules. Mindful of how tense this made me, I tried never to be a guest, and when I traveled I always chose anonymous hotels, beds with carmine quilts and panoramic watercolors over the head-boards, neutral, uninvasive rooms, to which I could bring my nightmares and my insomnia. I sought relief in being alone and yet I never was alone: as far back as I could remember I never had been, especially in the house in Messina. There, until I was thirteen, my solitude had been inhabited by my mother’s parents, who died before I was born: we had inherited the house from them, and it took them a long time to resign themselves to leaving it. They reappeared once a year, on the Day of the Dead, but I had the impression that they were always watching over it, even in my most embarrassing moments, when I was in the bathroom, or lost in secret fantasies.

In that same kitchen, Sara, the friend of my adolescence, had told me she had had sex with two boys at the same time; by then our bond had nearly dissolved, we were approaching one of those inevitable separations that mark friendships before adulthood, each the other’s witness of years we’re ashamed of and would like to forget; that afternoon, one of the last, when neither of us was quite eighteen, I envied her for what I would never have had the courage to do. I was sure that if I tried to have fun, the dead of my family would reappear at the foot of the bed to stare at me in silence; the dead are envious judges of all the actions they can’t perform anymore, of the errors they can no longer commit, of the entertainments of the survivors. My mother’s dead had remained in the house with the precise intention of knowing me, the granddaughter born after their passing. My grand-father, anticipating his own stroke shortly before it arrived, had brought the car to the guardrail and died on the highway, with the four emergency arrows flashing; my grandmother had developed cancer a few months after her husband died, and the house had thus ended up in the hands of their only daughter, my mother. The old people came back to see us the night between the 1st and 2nd of November, when I set bread and milk out on the table and the next morning found the milk half drunk and the bread half eaten, as well as an envelope with a banknote, the hard pure-white almond cookies in the shape of the bones of the dead that I gnawed on, hurting my teeth, and the marzipan fruits that were left uneaten, because they were nauseatingly sweet, and just looking at their perfection was enough to satisfy: sculpted and colored to resemble a prickly pear, a bunch of grapes, a slice of watermelon. That it was my mother who put on the clothes of the dead and performed the fiction didn’t matter, didn’t make that nighttime passage less true. That was death as I’d known it up to the age of thirteen: a straight, infinite line that had to do with heredity and the inescapability of time, a place people don’t return from except once a year for a celebration, an unfortunate but essentially fertile event. That’s what it was, and it didn’t frighten me.

Then one morning my father disappeared.

Not like my grandparents, already old before I was born, not like an accident or a heart attack that ends a life. Death is a full stop, while disappearance is the absence of a stop, of any punctuation mark at the end of the words. Those who disappear redraw time, and a circle of obsessions envelops the survivors. My father had decided to slip away that morning, he had closed the door in the face of my mother and me, undeserving of goodbyes or explanations. After weeks of immobility in the double bed, he had risen, turned off the alarm, set for six-sixteen, and left the house, and he hadn’t returned.

At seven-fifteen I got up for school—I was then in the last year of middle school—and I went to the bathroom to wash, crossing the hall as I had done since I was born, as I crossed it still as an adult: underpants, T-shirt, bare feet, and three-quarters of me still snagged in the night. On the kitchen table was the milk and the biscuits, but passing the bedroom I had felt an absence (the insufficiency of a place, its not being enough: not even the room-prison had been able to restrain him). For a long time my father had huddled between the sheets, with the psychic grief no one talked to me about, but I intuited a lot. I knew that he was there, and that after school I would pretend to have lunch with him; I knew that he wouldn’t eat and I knew that I would give my mother and myself a different version of the facts. But in my not-looking that morning was a perception of irrevocability.

I’ve often wondered if that wasn’t a story I invented later, adding what I discovered in the afternoon, that my father had gone, but that false sensation would still have been truer than the truth. Memory is a creative act: it chooses, constructs, decides, excludes; the novel of memory is the purest game we have. Coming home, I noticed from the street the new furor that animated the house, I heard it as soon as I turned the corner, like my mother’s crying. My mother was calling my father’s name, and as soon as I entered she attacked and suffocated me: Your father has gone, your father has left us. And even though at the police station they told us we had to wait seventy-two hours to report his absence, she didn’t want to wait even a day to report to me what she knew, what we both knew: a depressed man had consciously and forever left life and the two of us.

So at thirteen I became the daughter of someone who had disappeared: the real dead die, are buried, and you weep for them, while my father had vanished into nothing, and for him there would be no November 2nd, no calendar—he would no longer have one, and my mother and I wouldn’t have one, either. That year we didn’t celebrate the dead and the grandparents didn’t come to see us. In compensation, on November 2nd precisely I got my first period. As for the house, it had become the sacred place my father might return to at any moment, and now my mother wanted to sell it. What would become of him, alive or zombie or ghost, the day he showed up at the door, reclaiming his half of the bed and his place at the table?

*

The smell of burned coffee brought me back to the present, and I fixed my eyes on the kitchen wall, the only wall of the house adjoining another apartment. In the past a noisy family of evangelical Christians had lived there; at night my mother and I heard them through the wall, singing, while, unmoving on the couch, like part of the furniture, we stared at the television, gripped by our fiction of placidity, as if there had always been only the two of us, the two of us period. They’re singing, I thought, staring at the TV news. I forced myself to imagine seven people around a table concentrated on praising God, brothers, sisters, a mother, and then that other adult, the father, the word that was now so painful.

I thought: Why didn’t you talk about it anymore?*

“You burned the coffee,” my mother said, entering the kitchen with a bag of vegetables.

I thought: My father disappeared twenty-three years ago. “I got the coffee ready so you just had to turn it on.”

I thought: He disappeared into nothing and after the first days we never talked about it.

“I put a note in the spout the way your grandmother did with me.”

I thought: Why didn’t we talk about it anymore? “Have you been up long?”

I thought: Why didn’t you talk about it anymore?

“The workers are coming at eleven for the final assessment.”

__________________________________

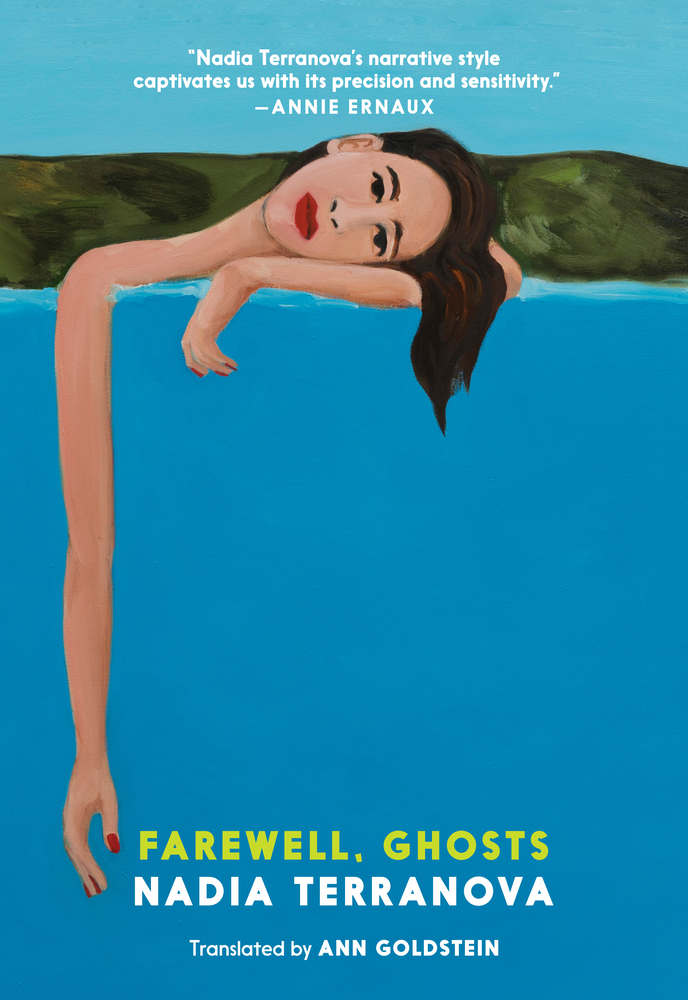

Excerpted from Farewell, Ghosts by Nadia Terranova, translated by Ann Goldstein. Excerpted with the permission of Seven Stories Press.