Famous Yet Elusive: On Charles Dickens’s Unstable Reputation

“Even in photographs it looked as if his soul had been ‘pumped out of him.’’

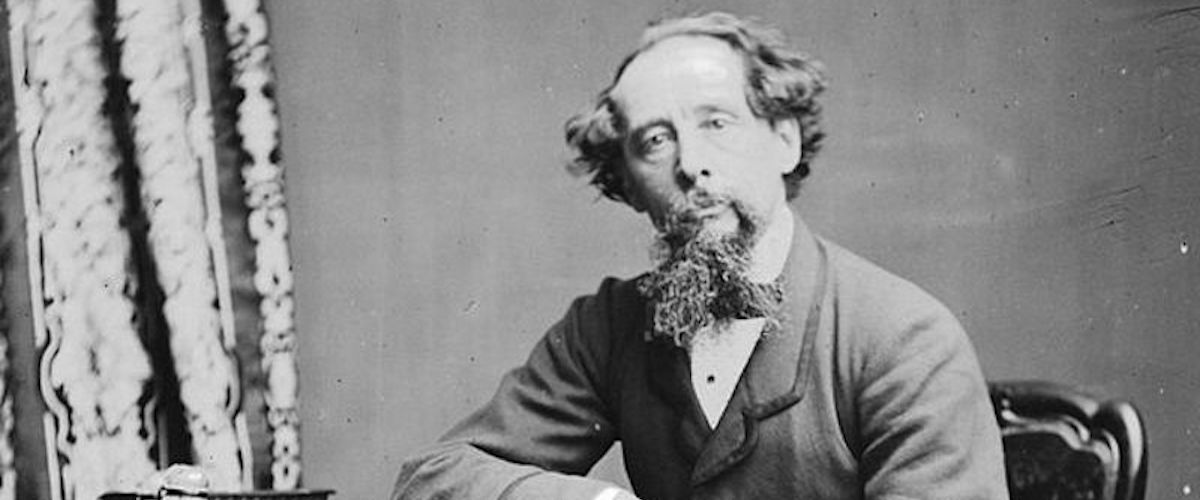

At the end of 1850, Charles Dickens, one of the busiest men in London and currently the most famous writer in the English-speaking world, agrees to sit for a new portrait by the painter William Boxall. The portrait is never completed, after Dickens notices that it appears to be turning into someone else. First, it is the notoriously ugly boxer Ben Caunt, a resemblance that probably occurred to Dickens because of the pun lurking in the artist’s surname: at the end of December, he writes that Boxall paints like someone sparring with the canvas, repeatedly dancing backward from it “with great nimbleness” before returning to make “little digs at it with his pencil.” Then it is the murderer James Greenacre, whose wife’s head had been found bobbing about in Regent’s Canal in 1837, and whose waxwork effigy had subsequently been displayed at Madame Tussaud’s. Finally, Dickens told the artist William Powell Frith, “I found that I was growing like it!—I thought it time to retire, and that picture will never be finished if it depends upon any more sittings from me.”

It wasn’t the only time Dickens would decide that a portrait hadn’t truly captured his likeness. In 1856 he told his friend John Forster that a painting soon to be finished by Ary Scheffer showed “a fine spirited head… with a very easy and natural appearance to it,” but “it does not look to me at all like, nor does it strike me that if I saw it in a gallery I should suppose myself to be the original.” A few years later he was equally suspicious of the latest engraving of a photograph taken of him. “I do not pretend to know my own face,” he told the artist. “I do pretend to know the faces of my friends and fellow creatures, but not my own.”

There seems to be more going on here than the usual worry that other people cannot see us in quite the same way we see ourselves. For Dickens, it was as if no artistic representation could ever depict someone with his famously fidgety energy. Kate Field, who attended Dickens’s American public readings towards the end of his career, observed that even in photographs it looked as if his soul had been “pumped out of him.”

Other images that survive from this period are no more successful. A daguerreotype probably taken in 1850 by the London photographer Antoine Claudet, still protected by its battered red leather and gilt case, shows Dickens trying to adopt a jaunty pose, with his left hand resting lightly on a side table and his right-hand thrust into his trouser pocket, but he looks decidedly awkward, like an actor playing a role he doesn’t quite believe in.

A drawing made the previous year by the journalist George Sala affectionately retains Dickens’s earlier pen name in depicting “ ‘Boz’ in his Study,” as the author reclines in his favorite armchair next to neat shelves of books. Yet while his legs are comfortably crossed, and his eyes gaze off thoughtfully into the distance, his right hand—his writing hand—is again hidden from view, reaching inside an embroidered dressing gown as if trying to keep a secret.

It was as if no artistic representation could ever depict someone with his famously fidgety energy.

Later images would attempt to make up for Dickens’s personal elusiveness by showing him surrounded by his characters: a version of “Charles Dickens” that deliberately muddled together the man and the author who had used his fiction to scatter his personality in many different directions. By the end of his career Dickens had created around a thousand named characters; even his incomplete final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, contained at least 40, including such human oddities as Deputy, a mysterious urchin who is paid a halfpenny by another character to throw rocks at him if he ventures out after 10 pm. And never before in the history of fiction had so many characters seemed somehow bigger than their stories. Showing them hovering around Dickens was therefore more than just a way of imagining what might have been happening inside his head. It captured the feelings of many readers that these figures seemed on the point of walking off the page and entering real life.

Contemporary verbal portraits of Dickens aren’t much better. “What a face is his to meet in a drawing-room!” wrote Leigh Hunt. “It has the life and soul in it of fifty human beings.” Other witnesses quickly realized that trying to pin Dickens down in a single description would be like grabbing hold of a handful of smoke. Surviving anecdotes from this period reveal many different versions of him: the dandy who combed his hair “a hundred times in a day”; the actor who gestured with “nervous and powerful hands” while telling a story; the stickler for accuracy who devoted his life to the creation of elaborate fictions, and yet savagely beat his son in public when he discovered that “He has told me a lie!…He has told his own father a lie!”

Perhaps this is why Dickens’s only surviving suit of clothes, the official court dress he bought to wear for a reception hosted by the Prince of Wales at St. James’s Palace on 6 April 1870, just two months before his death, seems curiously empty of personality without Dickens himself being present to strut about in what he humorously described as his

Yet the same clothes that allowed Dickens to stand out from the crowd were also an elaborate shield he could hide behind.

“Fancy Dress”; set up on a stand in London’s Dickens Museum, his hand-stitched wool tailcoat with gold trim looks more like a snake’s shed skin. Nor are reports of Dickens’s usual appearance any more helpful, perhaps because he always seems to have dressed as if he was on display. Caricatures of him published during his lifetime show a man gaudily encrusted with jewelry, making him look like a real-life Jacob Marley, whose ghost enters A Christmas Carol weighed down with chains and padlocks, while in 1851 Dickens appeared at a banquet “in a blue dress-coat, faced with silver and aflame with gorgeous brass buttons; a vest of black satin, with a white satin collar and a wonderfully embroidered shirt.” “The beggar is as beautiful as a butterfly,” sniffed Thackeray, “especially about the shirt-front.”

Yet the same clothes that allowed Dickens to stand out from the crowd were also an elaborate shield he could hide behind. While his contemporaries busied themselves describing his “crimson velvet waistcoats,” “multi-colored neckties with two breast pins joined by a little gold chain” and “yellow kid gloves,” the real Dickens could quietly slip away. Even the color of his eyes was hard to be sure about: some people said green; others hazel, or grey, or “dark slatey blue,” or black, or a muddy combination of them all. In effect, by the end of 1850 Dickens had established himself in the public mind as something more than just another writer. He was an escape artist. Novelist, playwright, actor, social campaigner, journalist, editor, philanthropist, amateur conjuror, hypnotist: he was like a bundle of different people who happened to share one skin. Every time his contemporaries thought they’d worked out who he was, he managed to wriggle free.

*

Dickens sometimes enjoyed playing up to the idea that his name was a plural noun. He created multiple nicknames for himself, which in addition to “Boz” included “Revolver,” “The Inimitable” and “The Sparkler of Albion.” In the late 1840s, after making himself responsible for the stage lighting in some amateur dramatic performances, he added “Young Gas” and “Gas-Light Boy” to his growing repertoire of alter egos. He later sent a letter to one of the cast signed by all the characters he had played, including “Robert Flexible” in James Kenney’s farce Love, Law, and Physic and “Charles Coldstream” in Dion Boucicault’s comedy Used Up, with each signature being written in a distinct style of handwriting. The fact that “Charles” came directly after “Flexible” seems more than just a happy coincidence.

At the same time, he was wary of his literary identity being diluted by the work of other writers. In March 1850 he launched Household Words, a weekly journal that aimed to tackle some of the most pressing issues of the day. “All social evils, and all home affections and associations, I am particularly anxious to deal with,” he had told a possible contributor in February. In practice this meant commissioning articles that would treat even weighty subjects like poverty or sanitation reform with a light touch, combining instruction and entertainment in a way that would appeal to readers who enjoyed this mixture in Dickens’s own writing, where it formed the characteristic double helix of his style.

“Brighten it, brighten it, brighten it!” he once instructed his subeditor W. H. Wills, after reading an article that was insufficiently “Dickensian”—a word that would soon be used to refer to any piece of writing that combined hard-hitting satire with sentiment and humor, whether or not Dickens himself was responsible for it. (Other coinages included “Dickensish,” “Dickensesque” and “Dickensy.”) Nonetheless, he was wary of contributors who tried to flatter him by writing articles that offered little more than bad impressions of his style, like a form of literary karaoke: in one letter that summer he grumbled about the “drone of imitations of myself.”

This problem was compounded by the sheer number of “Dickensian” plagiarisms and parodies clogging up the booksellers’ shelves. The early flood of literary rip-offs and knock-offs that had accompanied Dickens’s rise to fame—Oliver Twiss, Nicholas Nickleberry, and many more—might have abated, but there was still a steady trickle of publications that treated his style as a collection of narrative tricks that could be copied by anyone, rather than one that was as unique as a set of fingerprints.

s early as 1845, George Cruikshank’s Comic Almanack had printed “Hints to Novelists” that included advice on how to write in a style of “Weak Boz-and-Water,” offering an example that began with a description of a tumbledown building full of cobwebs and memories of “broken hearts and ruined fortunes,” in a part of London that is choked by fog: “It was a miserable November evening…” Clearly, one challenge of writing as Dickens was to offer readers something more than those who spent their time merely writing like Dickens.

In a period where the lives of writers were attracting more attention than ever before…Dickens had so far managed to achieve a remarkable level of fame while letting the public know very little about him.

His audience already stretched from the highest to the humblest. The Queen once pressed a copy of Oliver Twist on the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, after confiding to her diary that she found Dickens’s novel “excessively interesting”; at the other end of the social scale, his work was also appreciated by people like the elderly charwoman who every month attended a snuff shop where she listened to the latest installment of Dombey and Son being read aloud. When she was told that Dickens had been spotted visiting some lodgings she cleaned, she was astonished that just one person had been responsible for a story so full of life. “Lawk ma’am! I thought that three or four men must have put together Dombey!” She was hardly an isolated case. Thanks to the influence of his fiction on popular culture—so far it had generated theatrical adaptations, songs, catch-phrases, and even items of merchandise like Pickwick pastries and Fat Boy sweets—Dickens had become one of the few writers known by members of the public who couldn’t even read.

This created problems: in 1850 Dickens published an article on begging letters in which he confessed that those who had contacted him so far included one man who wanted “a great coat, to go to India in,” and another who asked him for “a pound, to set him up in life forever.” It also generated confusion. In a period where the lives of writers were attracting more attention than ever before, as could be seen in the revelation at the end of 1850 of the true identities of the three mysterious novelists who had published under the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell (Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë), Dickens had so far managed to achieve a remarkable level of fame while letting the public know very little about him. Already he had resisted the attempts of some early biographers to slip underneath his guard, telling one American editor with thin-lipped irony in 1842 that the “Life of ‘Boz’” he had published was “the most remarkable invention I ever met with.”

Yet despite his fame, Dickens’s reputation was still surprisingly unstable. It wasn’t just that he was personally elusive; his work was in danger of slipping out of his control. While a number of critics continued to praise his originality and humor, others were starting to wonder if he was a busted flush. Published in America the previous year, a book written by Thomas Powell had praised his former friend with one hand (“a man of genius… Mr. Dickens tells a story remarkably well”) while using the other to deliver some jabs at his coarse over-writing; whereas his earliest works were “undoubtedly his best,” Powell concluded, Dickens’s talent was “fast fading away.” Powell was a forger and thief who had only avoided prosecution in January 1849 after a court in London heard that he “was in a lunatic asylum, raving mad,” so it is unlikely that Dickens took his criticisms very seriously.

But they were only one version of an argument that had trailed his writing for a number of years, namely that he had been a far better novelist as the funny and original Boz than he could ever hope to be as the more serious and socially committed Dickens. As one journalist recalled, an “ancient female relative” of his who had thoroughly enjoyed Dickens’s early works, which “could tickle her into ringing laughter, or melt her into passionate tears,” used to warn him as a boy that “he has overworked himself—he has written himself out. Mark my words, my dear, Boz has written himself out.” Even Forster, whose biography of Dickens would later make every year sound like another step on the path to success, found himself cautiously returning to the word “perhaps” when looking back at this period of his friend’s life. The idea that Dickens’s most recent novel, David Copperfi eld, was driven forward by its characters “is to be said perhaps more truly of this than of any other of Dickens’s novels”; the author’s personal favorites were the Peggottys, “and perhaps he was not far wrong.” Perhaps, perhaps.

Other writers were quick to recognize that, even after he had confirmed his early reputation with popular works like A Christmas Carol, the trajectory of Dickens’s career continued to be far more wavering and uncertain than Forster later tried to make out. A short, strange book published under a pseudonym in 1849, which used the sketch of “ ‘Boz’ in his Study” as its frontispiece, The Battle of London Life; or, Boz and his Secretary, made Dickens a literary character in order to imagine his doubts over what his next novel should be. In the first chapter, he is seen “lolling in his favorite crimson-colored library chair” with his lips pursed and his eyes fixed on the ceiling; three hours pass in silence, while his amanuensis waits patiently for some sparkling bon mots to be thrown his way, but when “Boz” finally opens his mouth it is only to say “What next? what next?”

____________________________________________________________

Excerpted from The Turning Point: 1851—A Year That Changed Charles Dickens and the World by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. Copyright © 2022 by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst is the editor of Christmas Carol and Other Stories by Charles Dickens, author of Becoming Dickens (Harvard UP, 2011), winner of the 2011 Duff Cooper Prize, and has edited editions of Dickens's Great Expectations, Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, and Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies for Oxford World's Classics. He writes regularly for publications including the Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, TLS, and New Statesman.