A brisk knock on the front door and Frederick froze, like a setter with a bird in the bush. Another knock.

“Anyone home?” A woman’s voice. He didn’t know any women.

“Who is it?” He heard the voice of a scared old man.

“It’s Jan Venturi, from next door?”

The budgerigar woman. What could she possibly want? He left the box of books on the table and went over to open the door, leaving the security chain in place.

“Fred? Hello, how are you? It’s good to finally see you close up—or at least a bit of you. Hello, nose.”

He unchained the door and pulled it ajar, leaving his body in the narrow gap.

“I can’t get the wheel of my recycling bin out of the gutter. I’ve been at it ten minutes and it’s stinking hot. I was wondering if you’d mind giving me a hand. I’m sorry to bother you.”

“Of course, Janet,” muttered Fred, meaning of course he minded and of course she wouldn’t have any idea that he minded. He fiddled with the door and found his slip-on shoes, then made his way out to his neighbor, who was standing on the other side of the driveway, wrangling a large bin that was pitched sideways in the gutter.

“Terrible weather, isn’t it?” Jan called. She was tugging at the bin with one arm while keeping another hand on the stack of empty yogurt containers spilling out of the top.

“Awful,” agreed Frederick, hurrying over to help. How could anyone eat that much yogurt? He hated yogurt. As he walked toward her his left knee gave out and he stumbled.

“Are you all right there, Fred? Do you need a hand?”

“I’m fine, I just tripped on something.”

“Really? What was it?”

“A stick, I believe.”

“Of course, Janet,” muttered Fred, meaning of course he minded and of course she wouldn’t have any idea that he minded.

“A stick?” Jan said, casting around. “We should get rid of that. It’s dangerous. Where is it?”

“I kicked it over there,” said Frederick, gesturing vaguely toward the grass next to the driveway.

“I’ll just make sure no one else trips over it, then,” she said, scanning the open space. “The driveway, you say?” Jan left the bin and let yogurt containers spill down onto the path. She walked slowly across the driveway with her arms behind her back and her eyes on the ground.

“No, the lawn, but please, Janet, let me find it later,” he said. “Don’t you bother.”

“Call me Jan. No one calls me Janet except my budgerigars. That’s a joke, by the way. And it’s no bother. A large stick, you say? Over this way?”

“Actually, it was a small-to-medium-sized stick—and greeny-colored. Like grass.” Oh, god.

“Hmm,” she said, head bowed, looking left to right, “a small to medium grass-colored stick . . .”

“Please, leave the stick to me and let’s deal with this bin. If you could just pick up those yogurt containers.”

“Fine, Fred,” she said. “I was just trying to help.”

What an infuriating woman. Only his closest friends called him Fred, but he could hardly ask her to lengthen his own name straight after she had told him to shorten hers. He tried out her name in his head: Jan. Hi, Jan! There were many reasons not to chat to Janet—Jan—but the main one was she might want to become his friend, and Frederick did not want any friends. Jan tugged at her head scarf while Fred dragged the bin out of the gutter. He desperately wanted to ask her if she had seen Tom fall, and if she knew how he was, but he didn’t want Jan to know he had been standing inside watching Tom tottering around in the heat.

After all, it was a fine line between watching and doing.

It was called Mogumber when they went, but before that it was Moore River Native Settlement, where they brought what they called half-castes after they took them away from their families. Later they set some of that film there, the one about the Aboriginal girls who walked all the way back to Jigalong. He hadn’t wanted to bring Caroline to visit the mission, but Martha insisted; she had arranged it all and found a guide to meet them there, and they weren’t changing their plans now. They followed the woman around the compound and through the abandoned wooden cottages where they once housed the children. Had they checked the registers for relatives, the guide asked, all the while looking at Caroline. Martha shook her head, and they all fell in behind the guide. They stopped to look at old black-and-white photographs on a display board: well-to-do women in hats and gloves standing behind rows of barefoot Aboriginal children. It looked to him like the 1930s, but he wasn’t about to ask either the guide or his wife.

“Christians,” said the guide. “They drove up from Perth once a month to check on the children.”

“At least there were some white people back then who showed concern,” said Fred. “I suppose not all of them were heartless.”

Martha glared at him. Their guide shrugged. “It’s a fine line between watching and doing,” she said.

“Can we go?” whispered Caroline. “I don’t like it here.”

He tried out her name in his head: Jan. Hi, Jan! There were many reasons not to chat to Janet—Jan—but the main one was she might want to become his friend, and Frederick did not want any friends.

“Watch yourself,” said Jan, pulling at her scarf. Her hair was presumably tucked in somewhere underneath it, as if she were halfway through spring-cleaning. Or perhaps she was recovering from an illness. Not cancer, surely? He couldn’t manage that. He wheeled the bin down the side of her unit.

Jan gestured to the uneven paving at their feet. “Never mind the sticks, look at that! You could break your hip and that would be the end of it. I reported this to management weeks ago,” she continued, “and still no action, the cheapskates.” Frederick nodded in agreement. At least his neighbor thought the village was poorly run. This might be a good time to mention Tom.

“Speaking of sticks—” she began again.

“Did you get the letter about the latest extraordinary levy?” he interrupted.

“For retiling the pool, you mean? I prefer the beach. Tell me, Fred, where have you been since we last met? We were in the library, I think? Have you been back? I haven’t seen you there.”

And she never would. What they called “the library” was a dim alcove with a low teak table for the local rag and two small bookcases with his-and-hers Tom Clancys and Georgette Heyers.

Rather than answer, he set to work helping Jan reposition the paving stone.

“How are you enjoying the village?” Jan asked, rolling her eyes and laughing.

He smiled. So Jan saw what this place really was; it was not a village at all. A village was a small town in England surrounded by woods. A village was a remote community of weavers in the foothills of Nepal. This was a detention center. They were all refugees from youth and middle age who had been cut off from the normal ebb and flow of life and were being prepared for a slow and painful death. “I’ve been busy moving in, actually, Jan. It takes time to settle.”

“It certainly does,” she said quietly. “It takes some getting used to.” She stood with her hands on her hips, looking at him. “Thanks so much for the help,” she said. “I really appreciate it.”

Fred shuffled in his slip-ons and eyed his front door. “Well,” he said, “I suppose it’s time for me to—”

“Why don’t you come in, Fred? I’ve made a chicken pie and coleslaw and it’s not the sort of thing a woman should eat alone.” Jan patted her belly, which appeared to be a small firm mound.

“Oh no, I couldn’t,” he said hurriedly. Couldn’t, and wouldn’t.

“Oh, but you have to,” said Jan carefully. “It was hard enough for me to ask, let alone having you turn me down.”

Frederick ran his tongue around his lips.

“You have to come in, Fred, or else I will be unhappy all afternoon, and when I get unhappy I stamp my feet and flap my wings and cry very loudly.” She paused for effect. “And then the little fellows get upset and we wouldn’t want that, would we? You know how thin the walls on these places are.”

“Little fellows?” said Fred weakly.

“The birds,” she said, smiling. “Don’t look so terrified. You can at least take some pie home with you, can’t you?”

There was no way out of it now. Frederick waited as Jan fiddled with her keys. As the front door opened he heard an appalling flapping and screeching. The budgerigars. Frederick remained rooted on the spot. Once he crossed the threshold all would be lost.

“I think I hear my phone,” he said.

“Really? I’m amazed you can hear anything over my birds.”

“There it is again,” said Fred, cocking his head slightly. “Do you mind if I duck back?”

“I’ll take the pie out of the oven and let it cool. I’m pleased my birds don’t bother you. I was worried when you moved in that you might complain. I’m not supposed to have so many birds, but how will they know if no one tells them? Off you go now, big ears.”

“It’s stopped,” said Fred. He was defeated. It was pointless to either take offense or refuse the pie. And he did have rather large ears, and he had always hated them.

“Has it? Haven’t you got good hearing!”

Jan’s house was not at all what he expected. He had imagined a fussy, female kind of place, with doilies and mass-produced figurines in the sentimental genre, but his neighbor had a preference for simple, well-made wooden furniture and Asian art. There was a lovely mahogany Buddha on the floor near the sliding door, and scrolls of Japanese and Chinese paintings on the walls. On the face of her windows Jan had hung thin bamboo blinds, which filtered subdued light into the living room, where the one longer wall was covered with books.

“It’s nice,” he said, without thinking.

“Not what you’d expect from an old woman. No doilies and antimacassars? I do have the budgerigars, though.”

His neck reddened.

“My husband and I lived in Southeast Asia on and off for over fifteen years . . . Singapore, Bangkok, China. China was Sam’s last job. He was with a Japanese manufacturer who relocated their parts factory from here and needed a supervisor. I taught English at the local school and did volunteer work. We had a wonderful time. We traveled all over Asia—Vietnam, Mongolia, Japan, and then he got sick and we had to come home, and then, well, then Samuel died.”

Fred watched Jan’s face carefully. He waited for death to pass over and depart. Samuel. A biblical name, like Martha. “I’m sorry,” he said finally.

“Never mind,” said Jan. She sat very still. She was waiting for him to say the right thing. He could reach inside and pull out some words, just like he had done for the dean, or he could say nothing, as he’d done when he met Linda Yu.

“I want to see if you can guess my secret ingredients. Start, please, before it gets cold. Help yourself to salad.”

Jan’s pie was positively aromatic. It was absolutely perfect. He could not fault it. The crust was buttery yet crisp and melted away on his tongue, and the chicken filling was dense and juicy and firm and succulent.

“Well?” prompted Jan.

“Fantastic.”

“No, I mean the secret ingredients.”

“Onion?” he suggested.

“Hardly a secret.”

“Garlic?”

“Again, too obvious.”

“Parsley?”

“Closer, but no, there’s no parsley. You’ve dropped some pie on your shirt.” She handed him a napkin.

There was no way out of it now. Frederick waited as Jan fiddled with her keys. As the front door opened he heard an appalling flapping and screeching. The budgerigars. Frederick remained rooted on the spot. Once he crossed the threshold all would be lost.

Fred dabbed at his shirt, keen to return to his food. He had never tasted a pie like this. Martha was a wonderful cook, but after all those years even the best recipes wear out. “Sage?”

“You’ll be going for rosemary and thyme next.”

“I give up.”

“There are two secret ingredients—three if you count ground cashew nut.”

“Cashews? I think I can taste them now. And?”

“Fresh tarragon—dried is too overwhelming and kills the other ingredients. And finally, saffron.”

“It’s very good, Jan.” He was trying to hide his hunger. It was as if he hadn’t eaten a real meal since Martha died.

“Another slice?”

“Please!”

“Next week it’s your turn.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Next week it’s your turn to cook.”

Fred masked his alarm with a fixed smile. “I’m afraid I’m not much of a cook, Jan. I was always the sous-chef for my wife—the assistant.” A bald lie. Martha ran the kitchen with Caroline in tow, and he had happily accepted the division of labor.

“I know what a sous-chef is, Fred. Are you telling me that a big boy like you can’t cook? Samuel was what I call a book cook—someone who needs a book in order to cook. I’m more of an improviser in the kitchen, more of a Charlie Parker.”

“A book cook—I’ll have to remember that. My wife never allowed me to take the helm in the kitchen—you know what women are like. She insisted on cooking every meal. Of course,

I can open things and mix them together.”

He did not like the way Jan was looking at him.

“So what do you eat over there, Fred? At number 7?”

What did he eat? “Well, I have a toasted-sandwich maker and plenty of cereal. Healthy cereal, like muesli, with fresh fruit and yogurt. I love yogurt. Like you! And I have . . . I have beans.”

“Beans?” said Jan quizzically. “What sort of beans?”

“Large beans,” said Fred weakly. “And small beans.”

“Can you read, Frederick?”

“Pardon?” he said.

“Can you read?”

“Of course I can read.” Did she have to be so blunt?

“Because cooking is as straightforward as reading and following instructions. I heard from Tom Chelmsley that you were an engineer? You should be fine with the technical side of cooking.”

“Tom had an accident. I saw him fall.” It came out like a confession to Father McMahon.

Jan set down her fork. “I didn’t want to mention it until after the pie. Is that wrong of me? I’m very upset about it. Actually, that’s why I asked you in; I didn’t want to be here alone. I’m very fond of Tom. We have coffee most mornings. I cook for him: the poor man misses his wife terribly and he’s too old for cookbooks—not like you, Fred. Tom was married for sixty years. Can you imagine that? Poor Tom.”

Jan’s eyes were watering. Fred had a large, juicy piece of chicken on the end of his fork, just ready to pop in his mouth. He was starving. He lowered his fork and tried to concentrate on Jan’s face.

“Even though I complain, I like it here, in spite of the management. There’s no maintenance, I feel safe, and I’ve got friends if I need company. I can come and go as I please. But there’s no escaping what’s around the corner, and it gets me down.”

He nodded, and glanced quickly at the buttery pie on the end of his fork. Was it too soon to eat? Could he eat and listen?

“I think I must have been in the shower when he fell. They’d taken him away by the time I came out—I had the radio going and I had to wash my hair and, what with the birds, I missed the whole thing. Then Bernadette from number 10 called from the dining room to see if I’d go and check on Tom because he was late for lunch and they’d started on the soup. What’s wrong? Are you all right, Fred? It’s upsetting, I know.”

Fred jerked his head up. His gaze had fallen down to the pie again. “I’m fine,” he said.

“I usually go in and see Tom in the late afternoon. I take him a plate of food if he’s not up to going to the dining room. We have a cup of tea and I put on a load of laundry. He really can’t look after himself, but we don’t want the bosses to know that. They’ll have him out of there before you can say Jack Robinson. When he didn’t answer his door I called the office, and they told me he’d had a bad fall and that it was you who called.”

Fred nodded.

“Thank god you happened to look in the quad at just the right time. He could have been out there in the heat for hours. That’s the best thing about this place—you’ve got people looking out for you.”

Fred pushed his knife and fork into the finished position. He would not be able to eat his pie now.

“You can’t be full? You can’t leave it on the plate.”

“How is Tom? Have you heard anything?”

“Nothing. I hope he hasn’t broken his hip. That would be the end of him in his villa. At his age you’re never the same after an anesthetic.”

“I think it was his head,” muttered Fred. He really needed to go home and lie down. “I think he hit his head when he fell.”

“That doesn’t sound good. What was he doing out there all by himself? Where was everyone? I can’t believe no one saw him. He’s not exactly the fastest man on a walker; it must have taken him hours to get across the quadrangle. Why didn’t someone go and help him? I’ll put some plastic wrap on what’s left of that pie. Just bring the plate back when you can.”

He sat while Jan cleared the plates and wiped down the table.

“Would you like tea?”

“No, thank you, Jan. I really have to go. Lunch was very nice.”

“You are most welcome. Next time I want to hear all about your engineering. What was your area? Structural? Mechanical? Electrical?”

“I was at the university. Concrete.”

“Concrete? Well, that must have been hard!”

“Pardon? Oh, I see. I’m a bit slow at jokes.”

“Obviously—not that it was particularly funny. I blame Sam—it didn’t matter what I said, the man laughed. He thought I was a real comedienne. I can’t tell you how much I miss that. Here’s your plate, Fred—watch the edges, I don’t think the plastic is stuck down properly. What I miss most is having someone who likes me to make them laugh, someone who thinks I’m funny. What about you, Fred?”

“Pardon?”

“Your wife’s gone too, hasn’t she? I hope you don’t mind my asking.”

“Not at all. Martha, that was my wife’s name. Martha Salomon. Until she married me, and then it was Lothian. Martha Lothian.”

“Martha. What a lovely name. I’m sure she was a wonderful woman.”

“Yes, she was. She was a wonderful woman.”

“How long has it been?”

“Two years or so.”

“Only yesterday, really. Samuel has been dead for four years, three months, and twenty-two days. Tell me, what do you miss most?”

Something had set the budgies off again. It would be polite to ask about them—they obviously played a large part in Jan’s life—but he wasn’t really up to it. “I miss it all, Jan.”

“Fair enough,” said Jan, as if she didn’t mean it.

There were two photos on the wall near the front door. A fat baby was lying on its stomach on a sheepskin, stark naked except for a blue beanie with a logo from a football team Fred could not name. The second was the same boy, Fred guessed, aged about three. He was wearing oversized football shorts and holding a Sherrin ball.

“He’s a mad Eagles fan. That’s my only grandson, Morrison. He’s five now.”

“Your daughter’s child?” Fred wished he had missed the pictures completely, because soon the conversation would fold back toward him. He would be circled and targeted.

“My only son’s boy.” She paused. “He’s dead.”

“Morrison is dead?” His voice sounded shrill and hysterical.

“No, not Morrison; my son, Paul.”

“Your son is dead?” What could he do but repeat her misery?

“A year ago on Friday. He was dead for a week and I didn’t even know. He was a heroin addict. In the end I had to draw the line, for the sake of my sanity. We sent him to boarding school when we lived in Bangkok and Hubei. It was a terrible mistake. He fell in with the wrong crowd.”

“I understand,” said Fred. He thought of Katie.

“We should never have left him in that school.”

He ought to say more, but what could he say? “It happened to our best friends’ eldest daughter—many years ago. Her name was Katie. Katie Orr. It was a sad time for all of us.”

To his horror Jan’s eyes welled with tears. “Thank you,” she said quietly and opened the front door. “The boy is with his mother now. But not for long.” She raised her eyebrows.

There was clearly more to the story, but it was definitely time for him to exit. “Thank you again, Jan,” he said stiffly.

“You are most welcome, Fred. I look forward to our next meal. And I want to thank you.”

“Please,” said Fred. Don’t thank me, he wanted to say. I don’t want to be thanked. I don’t want us to owe each other anything.

Jan waited at he door as Fred crossed the driveway toward his villa.

“Fred?” she called out.

He gave a little wave without looking back.

“Watch out for medium-sized grass-colored sticks!”

__________________________________

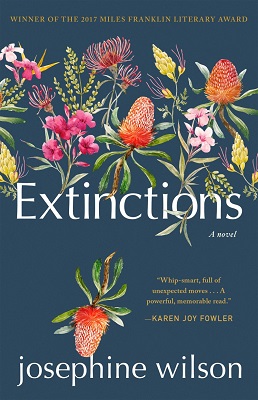

From Extinctions. Used with permission of Tin House Books. Copyright © 2018 by Josephine Wilson.