Exploring Octavia Butler’s Beginnings as a Sci-Fi Trailblazer

Susana M. Morris on the Early Writing of a Literary Icon

It was Octavia Margaret who gave her daughter the spark to even consider a writing career. She saw her quiet, bookish ten-year-old daughter writing, saw the delight on her face as she created, and asked her what she was doing. Estelle replied that she was writing a story. Her mother remarked, almost offhandedly, “Well, maybe you’ll be a writer.” That small word of encouragement set Estelle (aka Octavia E. Butler) on a path that would change her life.

Later she recalled, “[at] that point I had not realized that there were such things as writers and it had not occurred to me how books and stories got written somehow. And in that little sentence, I mean, it was like in the cartoons where the light goes on over the guy’s head. I suddenly realized that yes, there are such things as writers. People can be writers. I want to be a writer.”

Estelle had been scribbling down stories almost as early as she could write, but her destiny to become a science fiction writer was cemented on a seemingly ordinary day in Southern California. As a little girl, Estelle was obsessed with horses and wrote many of her earliest stories about them. On that day she was writing another story about horses in her big pink notebook when she decided to turn on the television as she wrote.

Even though the strict Baptist sect Estelle belonged to forbade going to the movies, her mama let her watch movies on TV at home—a loophole that allowed her a window into more secular entertainment. There were only a few channels, so there weren’t a whole lot of options. Twelve-year-old Estelle sat down in front of her family’s black-and-white television and saw that Devil Girl from Mars was on again. She had watched it at least four times already, and honestly, the movie was pretty terrible, more suited to be background noise than anything else. Estelle was a fan of more sophisticated shows like The Twilight Zone, not this B movie selection. The costumes were as threadbare as the plot, and the acting was a complete mess.

Yet for some reason, this time Estelle could not tear her eyes away from the movie. In the film, Earth’s rocky next-door neighbor is in a bit of a crisis: After a literal battle of the sexes, Martian men are dying out, leaving the domineering and oversexed Martian women in a terrible state. They send one particularly bold Martian woman—the titular “devil girl”—down to Earth and beam up some Earthmen to satisfy their carnal and reproductive needs. Although the Martian envoy has superior technology, in the end, the human men outsmart the alien invader and save the Earth from sexual slavery.

Estelle would grow up seeing a lot of powerful white men on her television screen telling people what to do.

Estelle cringed at the maudlin romances—How are they already in love? They just met!—and groaned at the raggedy special effects. The villain had a robot assistant that was clearly just a man in a suit. Plus, it was so obvious that the ray gun the Martian used did not destroy an actual truck, but just a miniature toy truck. Estelle rolled her eyes and thought, “Geez, I can write a better story than that.” Then she thought, “Geez, anybody can write a better story than that . . . and somebody got paid for writing that awful story.” This last fact inspired her enough to turn off the television and start writing science fiction in earnest. The story she began when she was twelve years old was the beginning of her critically acclaimed Patternist series. A science fiction writer was born.

Although Devil Girl from Mars was typical of the silly, schlocky TV fare that Estelle watched on many afternoons during her childhood, this movie was more than entertainment for a bored, lonely girl-child. Even if the filmmakers hadn’t planned it that way, Devil Girl was an education for a precocious young woman making sense of the world, identifying the patterns of behavior that reoccurred in society. On Estelle’s television screen she saw men—white men—cowering in the face of an all-powerful female alien.

Although the woman-alien’s powers were trumped up to comedic effect, Estelle could not help but see that beneath its B-movie veneer, Devil Girl from Mars tapped into a looming anxiety that was palpable all around. Modern women, embodied as a ridiculous but scary Martian, were challenging the status quo and pushing back against the patriarchy, the poor men who must defeat the alien threat. Estelle may not have had the language to describe that moment, but she got the gist of it. The combination of Devil Girl’s ridiculousness and transparent angst provided a necessary spark that lit her imagination.

Things were changing, and people—some people at least—were scared. It was 1959, a time when movements in support of civil rights, women’s liberation, and gay rights were slowly gaining mainstream attention, traction, and backlash. While the Korean War was a not-so-distant memory and the Cold War was already afoot, the United States would soon be reeling from the Vietnam War, sending tens of thousands of young men into battle and death. Estelle would grow up seeing a lot of powerful white men on her television screen telling people what to do. Men who invited Americans to ask not what their country could do for them, but what they could do for their country. Men who proclaimed segregation today, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever. Men who implored the country to unite. Men who turned water hoses and German shepherds onto Black children who could have been her classmates. Like these other men, the white men in Devil Girl from Mars reflected the signs of the times.

Devil Girl from Mars was initially released in 1954, seven years after Estelle was born. This was the same year that the Supreme Court overruled the mandate of “separate but equal” through the ruling Brown v. Board of Education. Estelle was born into a world swirling with change, a theme that would become so pivotal to her creative work, particularly her Parable series. She learned early on, even before that fateful day in front of the television, that change was not only inevitable but was, in fact, life’s only constant. Estelle also perceived that those in power would stop at nothing to make things stay the same. She recognized this watching her widowed mother work as a domestic for affluent white families. Was segregation outlawed not only in California but also in the whole United States? Yes, but that didn’t stop some employers from making her mother enter their homes through the back door. New laws also did not stop them from paying her mother mere pennies or insulting her as she cleaned their homes.

She became fascinated with how human beings—especially those who didn’t have much power—could empower themselves and others and change the world.

So, by the time Estelle watched Devil Girl from Mars on that fateful afternoon, she already knew about a world that was unequal and was afraid of those who lived on the margins. This was the pattern she pieced together from the world around her. It was these early experiences that made her ask questions about who had power and why. She became fascinated with how human beings—especially those who didn’t have much power—could empower themselves and others and change the world.

From then on, Estelle earnestly concentrated on writing. She went to school and church like before, but she put even more time into reading and writing. With few friends and no one who shared her niche interests in science fiction and fantasy, Estelle immersed herself in the fantastical world she found in books and in her own writings. Some of her post–Devil Girl writings anticipate stories and characters in her Patternist series. Some of the stories featured mature themes like violence and sex. Estelle was test-driving topics that would come to dominate her adult work.

Besides her frequent trips to the library, Estelle read and collected comic books, going into secondhand shops and scooping up cheap back issues. In fact, at one point, Octavia Margaret was worried that Estelle was too obsessed with comics and ripped all her comics in half. But that did not stop her daughter’s love of comics and reading or her desire to write. By the time Estelle was thirteen, she began sending her short stories out to magazines. Mr. Pfaff, her eighth-grade science teacher, even typed up one of her stories so she could send it out for publication. Estelle worked with a singular determination that defied the lack of traditional support. When other teachers tried to steer her away from science fiction, she avoided their classes. When family members and friends told her to concentrate on other pursuits, she kept her writing to herself. She forged her own path.

Besides practicing writing, Estelle’s teen years started her journey to becoming a polymath. At first, this was not a fully conscious desire. She had always been a curious girl who was interested in fields from history to biology to psychology, but during this time she initiated her own more formal study of the world. The 1960 election of John F. Kennedy as president helped inspire this shift. Estelle was thirteen, and around this time she became what she called a “news junkie.” She sat in front of the television taking in the news coverage of the election and found herself fascinated by Kennedy.

Whenever he gave a speech, Estelle watched in awe—and confusion. Kennedy sounded like he was speaking a language she could only partially understand. She just could not keep up—probably because of her youth and neurodivergence. At first, she internalized this, echoing her mother’s childhood distress and the negative feedback she herself had already experienced. Quite simply, Estelle felt stupid. Her diaries from this period were peppered with concern. Why couldn’t she understand what was going on? She was a voracious reader. She wrote all the time. Why didn’t Kennedy make sense to her?

It was then she decided that her education was not sufficient. She began watching the news in earnest and paying attention to politics, beginning a lifelong relationship with the news and current events that would show up in her work. And, perhaps most important, she began taking charge of her education. No longer a passive student, she became someone who observed the world incessantly and aggressively pursued knowledge, particularly outside of school and especially in the niche topics that interested her. This didn’t mean Estelle always got good grades, but it did mean that she focused on learning even when she wasn’t validated by others. This pivot would help fuel her intellectual pursuits and catalyze her life of the mind.

Her teenage voice is at once wryly observant, mischievous, and cutting.

Other circumstances fueled Estelle’s introspection. Throughout her adolescence, her life continued to revolve around the same narrow orbit of school, church, and home. Estelle’s high school diary from 1963 reveals musings one could find in a typical teenager’s diary. She discussed who was and wasn’t cute, covered conflicts with her friends, complained about homework, described drama at home, and mentioned the green-and-white patterned Easter dress her aunt Bee had bought for her. Sometimes she wrote in code or in Spanish to keep prying eyes from deciphering her innermost thoughts. Her teenage voice is at once wryly observant, mischievous, and cutting.

After falling asleep reading A Tale of Two Cities for an English class, she wrote, “Good Grief, I hope no one ever looks at my work with the attitude I look at Charles Dickens’s.” As a teen, she was already working out the character of Doro, a prominent figure in her Patternist novels, as well as reading and writing about telekinesis and psychic powers. All throughout her early journals are sprinkles of ideas she would later flesh out in her fiction. She swapped stories with fellow classmates who were also writers. Young Estelle’s diary reflects a precocious intellectual mind at work, someone already thinking of herself as a writer.

In another entry she wrote after church she declared there was “no message” in the sermon that day and that although the pastor remarked that God did not care about your denomination but only that you are born again, she wrote, “he may say that but half the people I know think their denomination and no other is right.” She was able to identify the hypocrisy in what was said versus how church folk felt about their faith. She also mused that the closest thing to a utopia would be a socialist or communist society, although she did not think a utopia was possible because people “will not live together without taking advantage of each other if they possibly can. They will not stop considering themselves better because their skin is light.” The roles of religion and hierarchy are some of the most salient themes in Estelle’s writing, and they animated her thinking early on.

Her diary also revealed issues she would struggle with for much of her life. In an entry from April 4, 1963, fifteen-year-old Estelle recalled crying in Spanish class after having to give a presentation. She had a phobia of public speaking, one that she would take pains to get over as an adult. Speaking to people outside of her family, especially ones she did not know well, was harrowing for her, and it was sometimes difficult for her to connect with her classmates. Estelle wondered: “I don’t know what to do about my personality (a fear of people and worms). I can’t talk to people the way I want to. They nearly all sense a difference in me. The[y] talk to each other, then they talk to me. What’s wrong?!!” Throughout her life she noted in her diaries and journals how she struggled with decoding social cues and saying the right thing at the right time; high school was a particular minefield.

She wanted freedom and independence—not the responsibility of babies or a husband.

Estelle grew to be six feet tall when she was about twelve, towering over young men her age. This did not help her social life or her dating prospects. She was occasionally mistaken for her friends’ mother, which did little for her self-esteem. Although she had crushes on boys, they were mostly unreciprocated. When guys did approach her, they sometimes mistook her for a boy or made fun of her appearance, which was both hurtful and confusing. Estelle’s church outlawed things that most young people enjoyed: “dancing was a sin, going to the movies was a sin, wearing makeup was a sin, wearing your dresses too short was a sin . . . just about everything that an adolescent would see as fun, especially the social behavior, was a sin.”

Still, she and her church friends would do things like roll up their dresses a bit in defiance of the rules. Estelle also noticed that her peers from church and her neighborhood rebelled against social expectations in striking ways. One ran off and got married; another had a baby while she was still in high school. Although she was curious about boys, neither of those options appealed to Estelle. She wanted freedom and independence—not the responsibility of babies or a husband. She made writing her rebellion, the main refuge from the strictness of her upbringing. Besides, her height and androgyny meant that some of the heterosexual coupling that her friends fell into was not quite available to her. And while she would later admit to being curious about queer sexuality, that was not a path she was interested in pursuing as a teenager.

Years later she recalled, “My body really got in the way of any social life that I was likely to have had. But, on the other hand, it did push me more into writing because I was in the habit of thinking about things.” In her fiction, such as Survivor, Dawn, and the Parable series, she would feature tall, androgynous Black women characters who are not only strong and resilient, but desired and desirable.

__________________________________

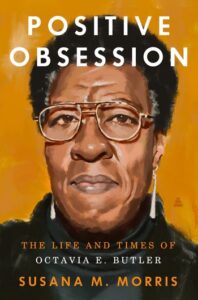

Excerpt from Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler by Susana M. Morris. Published by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2025 HarperCollins

Susana M. Morris

Susana Morris is Associate Professor of Literature, Media, and Communication at the Georgia Institute of Technology. She has been an Anschutz Distinguished Fellow at Princeton University and was most recently the Norman Freeling Visiting Professor at the University of Michigan. She is the author of Close Kin and Distant Relatives: The Paradox of Respectability in Black Women’s Literature, co-editor, with Brittney C. Cooper and Robin M. Boylorn, of The Crunk Feminist Collection, and co-author, with Brittney C. Cooper and Chanel Craft Tanner, of the young adult handbook Feminist AF: The Guide to Crushing Girlhood. She is the co-founder of The Crunk Feminist Collective and has written for Gawker, Long Reads, Cosmopolitan.com and Ebony.com, and has also been featured on NPR and the BBC, and in Essence and the New York Times.