Evolutionary Links: What Great Apes Tell Us About Being Human

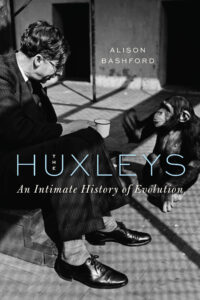

From Alison Bashford's Cundill Prize-Shortlisted The Huxleys: An Intimate History of Evolution

When we enter the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, with five million other visitors each year, we step simultaneously into the age of the dinosaurs and into the Victorian age. We inhabit a grand Romanesque hall successfully campaigned for by Richard Owen, still awed by the terrible lizards that he named, and that he had carefully boxed over from the British Museum collection in the early 1880s to the new site. We are drawn to Charles Darwin’s statue in the secular nave that invites cultural genuflection like Abraham in the Lincoln Memorial, like David in the Galleria del’Accademia, like a modest Jesus Christ in St Peter’s. Richard Owen’s own likeness used to be at the top of those stairs, but he was usurped and displaced in 2009, the Darwin anniversary, and now we have to search hard to find the old man to whom we owe a good deal, Huxley notwithstanding. There he is, up a level, in a nothing-place. The statue of Thomas Henry Huxley is nearer Owen than Darwin, and they still growl at each other.

And yet, for all this late-Victorian marbled hagiography, neither Darwin, nor Owen, nor Huxley is the real primate treasure of the Museum. Guy the Gorilla is. He now sits in his glass enclosure, taxidermied (actually latex-stretched, less-dignified, but more technically correct). Guy is displayed like a simian Snow White in her glass coffin, suspended somewhere between life and death. Like a thousand stuffed beasts before him, but also like marble Darwin, Huxley, and Owen, he is made to seem alive. In this strange, suspended afterlife, these four primates remain connected.

Julian Huxley adored Guy the Gorilla perhaps more than anyone, and in life, not death. His friend the extraordinary animal photographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, fresh from a Huxley family portrait session in Pond Street, Hampstead, caught Guy very much alive in what he singled it out as the best shot of a lifetime, noting also how much Julian loved both the photograph and the animal. This gaze is surely the steadiest and most commanding of centuries of intra-primate exchange, the ape’s reflexion.

Wolfgang Suschitzky, Guy the Gorilla, London Zoo, 1958. By permission, the Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky.

Wolfgang Suschitzky, Guy the Gorilla, London Zoo, 1958. By permission, the Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky.

Of all orders of animals, primates were core Huxley business, their appreciation of simians stretching from the wild to the captive, the historical to the filmic. Thomas Henry Huxley wrote one of the most famous “monkey books,” as Charles Darwin called it, of all time, Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863). It was hardly the first study of “man-like apes,” yet appearing at the height of the evolution controversy, the book focused attention freshly on the similarities and distinctions between humans and other primates, setting the shape of ideas for the rest of the century. Huxley’s work was directly antecedent to the great boom in primatology, catapulting controversy over the human-simian link well into the twentieth century where his grandson picked it up. Yet while T.H. Huxley preferred, or was forced, to study monkeys and apes dead, as skeletons or as soft anatomy specimens, his grandson looked at them living. Just as Julian watched the habits of the grebes as an animal ethnographer, so he came to value observational studies of primate behaviors. He was custodian of Guy’s predecessors, Moina Mozissa and Mok, lowland gorillas kept at the London Zoo between 1932 and 1938, and then Meng, a mountain gorilla who arrived in 1938. He engaged closely with key primatologists of the twentieth century, first Solly Zuckerman who studied captive apes, then George Schaller and Jane Goodall who spent years in Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania, their behavioral studies inspired by Julian’s ethology.

In this strange, suspended afterlife, these four primates remain connected.

Thomas Henry Huxley occasionally observed the chimpanzee and orangutan in the London Zoo, yet he never saw a gorilla alive. Rather, he encountered them as rare and precious specimens, in anatomy collections or in libraries; in scientific reports and in a tradition of printed African travel accounts from the 1500s onwards. These great apes were quasi-mythic to him, even though he put so much store on them in his search for evidence as to man’s place in nature. “Africa” too was mythic to the elder Huxley as well as his small-minded mid-Victorian critics who taunted at one point that he led a Gorilla Emancipation Society.[i] A century later, however, saving African gorillas and their native habitats from destruction was precisely, and seriously, Julian’s mission.

In 1947 London Zoo’s most famous creature ever arrived to replace the dead Mok. Julian couldn’t take his eyes off the great ape. “When I saw Guy at the Zoo this summer, I could hardly tear myself away.” Guy was the finest animal he had ever seen, domesticated, captive or wild. But when Julian received that special primate return gaze, Guy managed to stare the ethologist down: “Magnificence in his reserve and silent strength, he gives you a look of sombre dignity that makes you feel in some real sense his inferior.” [ii] Julian the great observer, felt watched. And yet eye contact alone was insufficient. He found himself wanting to talk with Guy. “If we could only get through the barrier of non-communication set up by their inability to talk, what strange areas of subhuman mind we could explore.” Julian struck through “subhuman” in his typescript for a BBC talk on Guy, acknowledging the primate’s mind as equivalent to his own, not a greater and a lesser, a human and a sub-human. The expression of emotion projected by this particular man onto this particular animal was plain.

____________________________________

The Huxleys: An Intimate History of Evolution by Alison Bashford has been shortlisted for the 2023 Cundill History Prize.

____________________________________

The photographs of gorillas kept in Julian Huxley’s papers signal his captive attention both to individual creatures and to the species. He kept a copy of Suschitzky’s magnificent portrait taken at the London Zoo in 1958. In many ways, it was framed by the convention of human portraits; in the convention, indeed, of the endless John Collier paintings of the Huxley primates. In fact, Suschitzky was the portraitist of this generation of Huxleys, over many decades photographing Julian, Aldous, Juliette and the Huxley sons, Anthony and Francis. The year that he captured Guy the Gorilla, 1958, he also captured the brothers, Julian and Aldous. It is another intimate portrait of fraternal primates, Julian characteristically talking and Aldous’s troubled eyes cast down, equally characteristically listening. It’s a moving image, especially when one knows the brothers’ past. Yet it has none of the strength of the portrait of Guy. In this image, we feel emotion in man and animal with the same kind of power that Charles Darwin experienced when he climbed into Jenny the orangutan’s cage, on occasion with a mirror. In this case, with a keeper’s help, Suschitzky passed his own reflecting machine—his camera—through the bars, to catch not the enclosing iron itself, but far more hauntingly, its shadows. Julian, like everyone else, was struck by the shadows of the bars across Guy’s face, across his very self. Perhaps this signaled how prison bars and cages were disappearing from zoo design and aesthetics—Monkey Hill anticipated this. The sign of imprisonment and captivity was being replaced by devices of apparent clarity and freedom—the suspended disbelief of a clear glass barrier, or of moats, zoological ha-ha walls, the kind of “sunk fence” that had been built instead of high walls at James Huxley’s Barming Heath asylum all those years before. But it was all disingenuous, and for human benefit only. There was no escaping the fact that Guy was captive and contained.

Julian and Aldous Huxley, by Wolfgang Suschitzky, 1958. By kind permission, the Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky.

Julian and Aldous Huxley, by Wolfgang Suschitzky, 1958. By kind permission, the Estate of Wolfgang Suschitzky.

Many years ago, the insightful art critic John Berger wrote an essay, “Why Look at Animals?” He cut through mountains of scholarship on zoos and beasts with the clarity of one simple observation: in the wild animals stand and watch us, nervous, ready to flee or to fight, never letting us out of their sight. In captivity, however, despite being close up and proximate, the last thing animals do is watch us, or hold our gaze: “nowhere in a zoo can a stranger encounter the look of an animal. At the most, the animal’s gaze flickers and passes on. They look sideways. They look blindly beyond.” [i] Yet there is Guy, staring down Julian Huxley and still holding our gaze with commanding power brilliantly caught by Suschitzky. Defiant in the moment, 1958, Guy unknowingly defied Berger’s insight. It is an excruciating image of life, especially when we try to hold Guy’s gaze in death, now in his glass case in South Kensington. Neither on all fours nor standing proud bipedally as man-like ape, Guy sits on a fake rock, a kind of miniature Monkey Hill, and stares blankly. Berger was right even about Guy: he no longer looks at us, but past us into a beyond.

Guy, a western lowland Gorilla, The Natural History Museum, London. Courtesy, Alamy.

Guy, a western lowland Gorilla, The Natural History Museum, London. Courtesy, Alamy.

[i] John Berger, Why Look at Animals? (1977] London: Penguin, 2009), 37

[i] Leonard Huxley (ed.), Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley, I, 194.

[ii] Julian Sorell Huxley, Guy The Gorilla typescript, 1958, Julian Sorrel Huxley Papers, Rice University, MS50, Box 74: 12.

__________________________________

From The Huxleys: An Intimate History of Evolution by Alison Bashford. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted with permission from University of Chicago Press.

Alison Bashford

Alison Bashford is Scientia Professor in History and codirector of the New Earth Histories Research Program at the University of New South Wales in Australia.