Searching For Agnes Martin

"Why does one artist fall in love with another’s art?"

In 2009 I started making poems in dialogue with the visual art and writing of Agnes Martin. I was at the beginning of what my friend the writer Miranda Mellis called “a healing crisis,” the most acute physical symptoms of which would last for five years.

In the foreground of this healing crisis were chronic illness and pain, exacerbated by economics. I’d lost a full-time teaching job to the Great Recession and had become fully adjunct; I had a previous medical condition, so I couldn’t buy health insurance; I found public health care first hard to access and then completely inadequate. In that context, my illness was undiagnosable, and the last doctor I could afford to see told me It’s all in your head.

The physical suffering was real, and yet in the background of this healing crisis was something psychological and nonverbal, hard to pinpoint. It manifested in my attachments to others, many of which became laden with an unspoken grievance: I could not get the care I needed.

*

So I turned to Agnes. Why? A friend, the poet Jean Valentine, had sometime in the early aughts praised her book Writings, which had been circulating among poets the way Gnostic gospels must have once circulated among Christian heretics. Rumors of Writings came with the aura of secret wisdom. Copies were hard to find.

I came across the talk “The Untroubled Mind” in an anthology of artists’ writings and felt at once that the aura was justified – here was a form of wisdom literature written by an artist for other artists. Dictated to and transcribed by her friend the artist Ann Wilson in 1972, it even moved like a poem on the page. In almost all of her writings, Agnes cultivates a persona part mentor and part guru. The voice is at once didactic and oracular, practical and metaphysical. There is a distinct and total verticality that puts the reader in their place: at her feet.

Not everyone would want to sit there, but desperate as I was at the time, I bowed down and studied “The Untroubled Mind,” which promised that art held the possibility of “more perfection than is possible in this world.” Then I lucked across a battered copy of Writings and it became a sacred text I took with me everywhere.

*

I wrote my first book in dialogue with Agnes, The Empty Form Goes All the Way to Heaven, from 2009-2014, a time when there wasn’t that much public information about Agnes herself – a dearth she created in part so that critical discourse would focus on her work. She did not then have the same high profile and near-ubiquity she enjoys now.

So, like other queer artists before me – Douglas Crimp and Jill Johnston among them – I sought her out. Because she died in 2004, I never made a pilgrimage to New Mexico. Instead I read her Writings, art criticism about her, reviews of her work, and the books that were then just beginning to come out. I looked at reproductions of her paintings and drawings in monographs I borrowed from the library, and when I could, I sought out the real things in museums. I visited nearby archives that held documents, papers, and correspondence related to her exhibitions.

Given the relative lack of biographical information about her, the Agnes I wrote about in The Empty Form was especially susceptible to projection, and because in Writings she presents herself as a metaphysical-aesthetic disciplinarian, she was bound to arouse mixed feelings. “Just follow what Plato has to say,” she advises. Plato, who kicked poets out of the Republic! By 2015, when The Empty Form came out, the Agnes I perceived in Writings just pissed me off.

*

Why does one artist fall in love with another’s art? At first, my attachment to Agnes’s aesthetics felt a little random. Though “The Untroubled Mind” became something like a sutra for me, much of it rubbed me the wrong way. “I don’t believe in the eclectic,” she writes, “this is a return to classicism.” It’s hard for me to reconstruct the mindset I had at the time, the one in which dissing my own eclecticism in favor of her classicism (it’s hard for me not to hear “classism”) seemed like a good idea. Except that, according to Agnes, “the detached and impersonal” offer a way out of personal suffering, an escape from the chaos of what she called “the involved life.”

Because of the promise implicit in lines like “This painting I like because you can get in there in rest,” I repressed my misgivings. And besides, I never felt ambivalent about the drawings and paintings of hers I loved most. I fell especially hard for the art she made in the 1960s when she lived and worked on Coenties Slip, the early grids that were her hard-won breakthrough as an artist. The paintings and drawings I like best from those years retain more obvious imperfections, more evidence of the process of their making, than her later work, and yet in the atmospheric abstraction of their optical effects they do reach toward a perfection not of this world.

“Painting is not about ideas or personal emotion,” she says, “When I was painting in New York I was not so clear about that.” Thus the construction, materials, and colors are, yes, more dramatic than the horizontal lines and pastel colors she would come to favor later in New Mexico. Still, it took me a while to figure out that the Agnes who made grids in New York was not the Agnes who dictated to Ann Wilson “The Untroubled Mind,” which dates from after her one of own healing crises, the one that in 1967 prompted her to give away her art supplies and leave the city for good.

*

Agnes wouldn’t paint again for nearly seven years, and when she returned to the work she had a clarified formal vocabulary to match her metaphysical one. By 2015 I would hold a grievance against this later Agnes, but it took me until then to work my way from distant adoration to loving intimacy to active ambivalence. The Empty Form records these shifts in the way the poems name her: in the book’s first section she’s Agnes Martin; in the second section, she’s Agnes; in the third, she becomes the teacher Agnes. By the third section’s end, I part ways with her.

Why does one artist fall in love with another’s art? At first, my attachment to Agnes’s aesthetics felt a little random.It’s what she would have wanted. Don’t be fond of me, she writes in an archived letter, Let’s not be friends. Let’s be companions of the open road. Though her grids gave the poems of The Empty Form a formal vocabulary that allowed them to perform with tact and restraint the uncertainty, contingency, and precarity of chronic illness and pain, her famous phrase about turning her back to the world never sat well with me. Illness and its resulting disability were social and political situations made worse by capitalism and ableism: immersed in material conditions I shared with others, I struggled with pure abstraction as an ideal and the ultimate goal.

Perfection not of this world began to feel like a failure to reckon adequately with this world, which she dismisses simply as “chaos.” “If you don’t like the chaos you’re a classicist,” she quips, “if you like it you’re a romanticist.” Though I’ve always enjoyed the wit of that tidy aphorism, I resisted it on several levels. Liking felt beside the point; the world is simply a given. The real question is: what are you going to do with it? “The object is freedom,” Agnes says, “freedom from ideas and responsibility.”

Towards the end of writing the book I realized that “The Untroubled Mind” was full of ideas about renouncing ideas. And though Agnes turned her back to the world, she was nonetheless still in it, as were all those pricey paintings hanging in wealthy institutions. These paradoxes made me laugh and my laughter changed my relation to her. We were definitely not friends. Our open roads led in different directions.

*

In 2021, the Philadelphia Museum of Art commissioned me to write about Jasper Johns in honor of his massive Mind/Mirror double retrospective. Though he and his paintings proved to be provocative objects in their own right, I found I couldn’t write about them without Agnes and her grids as equal counterpoints, especially once I learned that Johns lived mere blocks from her in lower Manhattan. I also found I couldn’t write about their art without writing about the five years of acute physical illness and, obliquely, two more recent years of psychic crisis.

But the Agnes I write about in Poem Bitten by a Man is a different figure than the Agnes in The Empty Form, though of course they are based on the same historical figure. When I published The Empty Form in 2015, I didn’t think my conversation with Agnes could or would continue, but that year was the beginning of a small, steady stream of books about her, starting with Nancy Princenthal’s biography. That book, along with a monograph edited by her dealer, the Pace founder and gallerist Arne Glimcher, shifted my relation to her.

I didn’t know until then that she had a psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia, and that she had been hospitalized during what Western medicine calls psychotic episodes. Agnes preferred to talk about herself in different terms—as hearing voices and having visions—and, as I understand it, her entire artistic practice was guided by what she characterized as visionary experience. In fact, her entire adult life was shaped by voices, visions, and the states that sometimes accompanied them. It was after she was hospitalized for what doctors called a “psychotic break” that she left Coenties Slip and abandoned her art in 1967.

*

One aspect of Agnes that I carried from The Empty Form into Poem Bitten by a Man I first saw in Mary Lance’s documentary, a film that, like Agnes’s late paintings, studiously eschews drama. This one riveting scene especially sticks out. Facing the camera, sitting in a wooden chair in her studio, Agnes offers Lance an astonishing monologue – we don’t know what question prompted it – in which she says

I can remember back very easily

I can remember the minute I was born

I think everybody’s born in exactly the same condition

I thought I was quite a small figure with a little sword

and I was very happy

I thought I was going to cut my way through life

with this little sword

victory after victory

I was sure I was going to do it

I think everybody is born 100% ego

and after that it’s just adjustment

(chuckling)

well I adjusted as soon as they carried me into my mother

about twenty minutes later

half of my victories fell to the ground

(chuckling)

my mother had the victories

I’ll tell you she was a terrific disciplinarian

and I imitate her

Into my notebook I transcribed that monologue in the style Ann Wilson used for the “The Untroubled Mind.” I noted in particular how heavy its content felt and how lightly its delivery held it. The relation Agnes describes between herself and her mother resonated with me – both the sense of intrinsic power (ego) and the severe curtailment of that power by one’s mother. In the startling phrases of her monologue I sensed a story more complex than the ordinary ego formation fostered by attachment.

*

In 2009, I turned toward Agnes because I needed something from her as an artist and thinker. I hoped that by following her advice in “The Untroubled Mind” I could endure a healing crisis by accessing a mind untroubled by chronic illness, pain, and economic precarity.

In my own attempt at classicism, I pared down my lines and arranged them in patterns on the grid intrinsic to the typeset page. Most of those poems offer multiple ways for the reader to read them and enter into relation to semantic meaning. The grid allowed me to stop overdetermining the reader’s experience, and in doing so, the poems hover on the lip of abstraction before the reading mind pulls them toward representation. Something about this pause – the one before meaning gets made – felt like a painting in which to find rest.

In 2021, I returned to Agnes because I had come through crisis to identify with her as a queer artist of the 20th century, a person who lived with sexual and psychological difference and figured out ways to keep going. In writing Poem Bitten by a Man, I came to understand my own lifelong practice of making as a recursive form of mending, the act of repairing my relation to a world that has never held back its hatred of me.

I won’t recount here specific experiences of such hatred. The point is: inside me, they persist, wordless, embodied, and abstract. Somatic events, synesthetic experiences that resist translation, these agonies are sensoria of texture, weight, and color.

*

One appeal of collage is its intrinsic aggression: cutting comes before pasting. In writing Poem Bitten by a Man I came to think of each cut as a bite, each pasted phrase a loving form of repair. So though I use collage to try to capture traces of the somatic states the agonies produce, I also use collage to pay homage to the visual art and writing that have caught me, time and time again, when I feel myself falling into crisis.

I can’t say that for Agnes the practice of painting served a similar purpose, but in writing Poem I came to my own understanding of her later work. I no longer felt disappointed by those pastels and horizontal lines. All along she was listening to the voices only she could hear. The truest companions of the open road she chose to travel alone, they gave her visions she could use.

When in 2009 I began writing in dialogue with Agnes, it never occurred to me that her grids might be her own form of mending, the grid the shape it took to repair her relation to the world. Instead, I saw her through the persona of “The Untroubled Mind,” the way, I think, she wanted to be seen by the public: a person of certainty, wisdom, and authority.

In 2021, I began writing in dialogue with a different Agnes, one who struggled with herself and changed over time as she developed her way of being in the world while making art about a space beyond it. Given her birth year of 1912 and the Cold War era in which her career first took shape, I could now understand why she did not want to be seen as a woman artist, let alone a lesbian, let alone a lesbian who first receives her paintings as visions accompanied by voices. And I could also understand why, given her art’s ultimate goal, she eschewed both the social and being social. By 2021 I had disambiguated myself from her and her disciplinary ways, which allowed her to be an Agnes, and allowed me to be a Brian, situated in different historical and personal contexts and driven by different imperatives.

*

“You can’t get away from what you have to do,” she says in “The Untroubled Mind,” and what I have to do as an artist is not what an Agnes had to do. And yet in 2021 I was drawn back to her life, her philosophy, and her grids. This time, it had nothing to do with the urgent wish to free myself from suffering. It had everything to do with saying of suffering, to use a phrase from Jasper Johns’s sketchbooks: “It is what it does. What can you do with it?”

In 2021 I was able to be curious about suffering as a material with plastic possibilities like those of paint. This curiosity signaled a freer relation to crisis, and enabled me to see how Agnes’s aesthetic philosophy was informed by having what others would call a “troubled mind.” I felt more capable of holding her relentless edicts as steps in the path an Agnes took toward “independence and solitude,” “freedom from suffering,” and “the purification of reality.”

The life circumstances in which they were produced don’t reduce her incredible paintings and drawings to symptoms in the same way that the philosophy behind them doesn’t overdetermine their effect on viewers. “The response depends on the condition of the observer,” she writes in “Response to Art.” Of course, she was completely right.

__________________________________

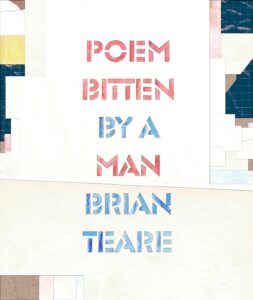

Brian Teare’s collection Poem Bitten By A Man is available from Nighboat Books.