I didn’t mourn for Vivienne Bianco. I didn’t know her. I knew how she died, though, because Randall Smiley told me the whole terrible story. I couldn’t get Randall’s story out of my head. I was never again going to let myself forget how each breath was bringing me closer to my final breath. How would I live differently? For sure I didn’t want to live the same life I’d been living. I craved revolutionary changes in my life. Violent changes, even. I felt like I was exercising a new muscle in my body. My body began to conform to my new way of thinking. Each day my body grew more loose-limbed and intuitive. It grew more sensitive to things. Trivial things at first, like the way my clothes felt against my skin as I walked along. Then larger things, too, and larger-than-large things—profound things, even—like the boundless sky at dusk when work was done. A slant-sun would be making its way toward the horizon, and the east-west roads would be orange and glowing. The traffic would begin to shift feverishly in all directions, and my body would tremble on the breezes—and away I would fly, like a muscular swan. Or so it seemed to me.

The year was 1974. I was nineteen years old. Newspapers kept running a photograph of an internationally famous heiress toting a machine gun while wearing a saucy beret. One day on my lunch break I bought a saucy beret for myself, at a hat store on Market Street. There were hat stores in those days. Berets were fashionable among radicals and the very old. The world was a noisy, crowded place in that era. You couldn’t walk down a simple street without your head intersecting with a radio wave or a casual sidewalk conversation.

I worked for the phone company that year, in the Resident Billing Office, on the third floor of a six-floor building on Fourth Street in San Francisco. Randall Smiley worked on the same floor as I did, but six rows over. Our job was to make people pay their phone bills. The job was uniquely powerful because in those days the telephone was all there was. No world wide web. No texting. No picturephones, either, although they’d been promised to us ever since the New York World’s Fair in 1964. If you wanted to speak to somebody who wasn’t within shouting distance then you talked through a box, attached with a wire to a wall. Back then the phone was so important that we who worked in the Resident Billing Office were like harsh cold gods. If you didn’t pay on time, or if we didn’t like your tone, or if you disrespected us, then we could disconnect your phone as fast as a fingersnap and you’d be dead to the world. We called it ripping your lips. We’d say: “Don’t get testy with me, Mister Customer! If you don’t pay up by Friday, I’m going to rip your lips!”

But our job was uniquely powerless, too, because for eight hours a day we were tethered to a short cord attached to a headset. We were forbidden to leave our workstations unless we got permission. To get permission we needed to hold up a little paddle. Then we needed to wait until the floor supervisor noticed the paddle and excused us. The floor supervisors were all men who didn’t understand about menstruation. All day long they sat up on a dais at the front of the room and surveyed us like petty dictators, with their arms crossed. On any given day the floor supervisor might decide to flex his petty-dictator muscles and pretend not to see our paddle and leave us bleeding or peeing in our pants or otherwise embarrassing ourselves.

The queue of customers calling in to explain why they hadn’t paid their phone bills never ended. Every three minutes a different voice made its way into our ears. Three minutes was all the time we were supposed to take on each call. The voice might be drunk, or belligerent, or hostile, or afraid of the dark. The voice might be suicidal. The voice might be full of desperation. By the end of each day an everlasting chorus of voices filled our heads. Berating us. Pleading with us. Threatening us. We weren’t supposed to hang up. The best we could do if a customer was drunk or obscene or abusive was to switch the call over to a floor supervisor. Once a floor supervisor took over the call then those randy, rowdy voices would settle down, usually. They’d respond to a floor supervisor’s voice differently. They’d be gentle and polite and reasonable. When the call was done, the floor supervisor would come over to my station and say, “What’s the matter with you, Celia? That man was a perfect gentleman. You must have done something to rouse him!”

Our work life was so regimented that we needed to find drama elsewhere, in our off-hours.

Here is the drama Randall Smiley found. He was carrying on with Vivienne Bianco.

*

Vivienne worked at the phone company, too, but she was four steps up the corporate ladder from Randall and me. Sometimes she wore a yellow suit to work. Sometimes a navy one. No matter what the color of her suit, her blouse was always tastefully cream-colored. She had the typical rigid stern posture that all career women of that era adopted. Solid shoes. Big bows. Beyond sharing an elevator with her now and then—I worked on the third floor, and she, the sixth—I didn’t know Vivienne Bianco. None of us knew her. She was literally on another level from us Resident Billing workers, and for the life of us we couldn’t understand why she’d chosen Randall Smiley, of all people, to be her love nest companion, because Randall was shaped like a beach ball with legs sticking out below and his hair was unwashed. Randall had lovely strong hands, though, and he spoke in a manly and commanding voice. His was the kind of voice you could imagine coming out of the mouths off our-star generals or sea captains. And maybe Randall had other fine qualities, too, not to be perceived in the course of daily polite society, and maybe he felt like a safe bet to her, because for sure she’d never run across him accidentally at one of her fancy corporate soirees or at a neighborhood bridge party. She and Randall moved in different circles. All these speculations kept us billing operators busy gossiping about Vivienne and Randall on our breaks, and we could never agree on what had brought those lovers together, because the ways of love are meandering and mysterious.

The two of them used to go to her place in Pacific Heights.

One day her husband came home at an inopportune time.

“Get under the bed, get under the bed!” Vivienne ugly-whispered, and Randall had done exactly that, squeezing himself under the bed—but in their panic the two lovers forgot to attend to the used condom on the floor. Talk about incriminating evidence. The rest of us could only imagine Randall’s sickening embarrassment at needing to testify at the trial.

But wait. I’m telling it all wrong. It’s because of the paddle situation.

Let me try again.

__________________________________

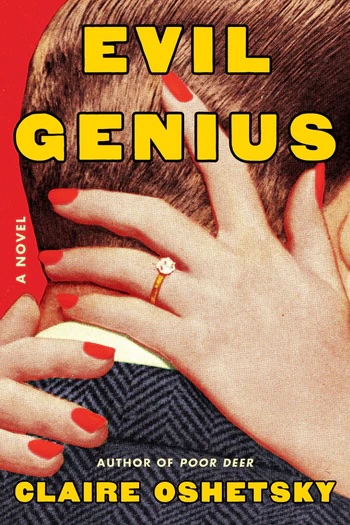

From Evil Genius by Claire Oshetsky. Copyright © 2026 by Claire Oshetsky. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.