Everyone Can Be a Book Reviewer. Should They Be?

Phillipa Chong Surveys Professional Book Critics

“Anyone can be a critic.” It’s a common lament these days now that the book review landscape is changing. English professors and book reviewers in newspapers aren’t the only tastemakers in literary criticism anymore: Goodreads community members, anonymous or top reviewers on Amazon, and dedicated bloggers can, and do, produce discourse about books. But are they really critics? And should we take their work seriously?

Plenty of my interviewees in Inside the Critics’ Circle—critics at newspapers and magazines—grapple with these question themselves. They often define their role in the book review world by contrasting their work against that of academics and amateur reviewers.

Critics were understandably ambivalent towards amateur reviewers despite their appreciation for general readers’ enthusiasm about books. In the words of one anonymous critic, “I think it’s wonderful if people read and come up with their own opinions. I think it’s a marvelous thing. There’s nothing that says any particular group of people have a monopoly.” Yet, this same critic is skeptical about amateur reviewers’ qualifications to write a well-balanced book review: “I do sometimes think that bloggers are kind of dumb, as a general rule.”

One critic bemoaned the ways people on Amazon evaluate books:

The Amazon.com reviewers, it’s like they’re reviewing a product. It’s like they bought a pair of Nikes and they are going on and saying, “Oh, my Nikes feel just great, they fit perfectly and I love them.” Then they go on and review a book and say, “Oh, this book was too long, I got really sleepy halfway through,” and just stuff like that.

For many professional critics, books are art forms that should be discussed and evaluated as such, which is a privilege journalistic criticism affords. But amateur reviewers weren’t seen as the only threat to reviewing culture.

If the critics I interviewed were concerned that amateurs did not bring enough analysis to their reading or lacked credentials to speak to a book’s artistic merit, they had equal concern about the over-intellectualization of book reviewing.

Academic critics are commonly invited by review page editors to write reviews for more general publications, such as newspapers, by dint of their literary expertise. However, many critics—including those who are also academics—expressed concern that literary scholars couldn’t always “code switch” to make their specialist form of criticism accessible to general readers looking for a straightforward review.

The retrenchment of book reviewing has been coupled with the economic fortunes of newspaper media.

Some reviewers found this inability or reluctance to code switch irritating. When asked about academic critics whose work he disliked, another reviewer offered: “I can think of many that are academics that I find absolutely boring because they are trying to fit a book into some sort of theory. And I find that abusive, violent to the book and to the author.”

More than a matter of differences in approach, however, reviews rooted in pedantry were seen as doing a disservice to general readers. The fault lies not in academic critics’ literary competency but an approach to the evaluation of books that threatens to cast serious reading as too rarified, making it irrelevant for the average person.

So where does this leave book reviewers in newspapers and magazines?

Traditionally, newspapers have been the organizational base of arts reviewing. The retrenchment of book reviewing has been coupled with the economic fortunes of newspaper media. However, I think its position and history with the newspaper qua journalism represents one of the greatest strengths of journalistic reviewing.

Book reviewing is a form of journalism. More than a report on publishing industry news, book reviews situate literature in the here and now, and make it accessible to the public. People often focus on the commercial nature of book publishing: do people use reviews to buy books? How can reviews compete with algorithms that make recommendations based on your browsing history? They don’t have to do that.

Then there’s the idea that reviews are esoteric, long-winded, irrelevant essays. They don’t have to be. Reviews have an opportunity to explain how books connect to the world around us. As one critic put it:

In the same way that reading a story about a bill in Congress is not really necessarily going to make every person an activist, a particular book review is not going to necessarily make everybody a reader. But [it] is going to hopefully lead to a more informed citizen.

Good books—and good art—to me, have always been about reflecting something about our shared social world back to us in hidden ways. Book reviews can help us decode that. Book reviews are reflections on what artists are doing and saying. They can help us become more informed citizens and recognize our humanist orientations.

Everyone has a right to write about books. The more the merrier. But we all have different things to say about them. Books are complicated. They are nuanced. They can have multiple meanings. And people use them in different ways: for work, for study, for a weekend getaway, for book club conversation, for enrichment. Why should we expect our reactions to them, in writing and otherwise, to be any different?

______________________________________

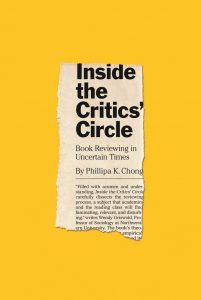

Phillipa K. Chong’s Inside the Critics’ Circle is out now from Princeton University Press.

Phillipa K. Chong

Phillipa K. Chong is assistant professor of sociology at McMaster University. You can follow her on Twitter @ChongSOC. Her book Inside the Critics' Circle (Princeton University Press, 2020) is available now.