“Every Page Holds an Answer.” Lily King on Shirley Hazzard’s The Evening of the Holiday

In Praise of a Great Literary Love

Loving a book is a lot like loving a person. It’s easier to know it, to feel it, than to explain all the ways. One of the greatest loves of my life has been the short novel The Evening of the Holiday by Shirley Hazzard. I have kept a copy of it on the desk where I write for more than twenty-five years. I reach for it when I am stuck, scared, or bored, when I am at loose ends or bound up tight. I raise it like a sacred text, let it fall open where it will. Why do I do this? is what I am asking.

Every page holds an answer.

I might land on a fragment of poetic detail: “a blaze of flowers by the hotel window” or a little boy “eating an ice cream cone aloud” or a woman wearing “a simple dress of a splendid color, the sort of dress that might turn up in one of his memories.” Or a reference to Petrarch or Pisano or Renoir, the Second World War or 1416. Or one of her falcon-like narrative dives from a great omniscient height deep into someone’s heart in the space of sentence. Hazzard makes an art of restraint, of feelings withheld then revealed in one staggering brushstroke. But ultimately what moves me most about The Evening of the Holiday is the way Hazzard captures love on the page: falling in love, being in love, losing love.

The novel begins here:

“Tancredi,” Gabriella said to her brother, “you must show them the fountain.”

“All in good time, my dear,” he replied irritably. “Let’s have our tea in peace.”

Gabriella might as well have said, “Tancredi, go fall in love for once in your life!” and her brother would have given her the same reply. He is not up for it. Tancredi is living with his sister in the Italian countryside because his wife has left him and this afternoon he is stuck in her living room with her guests, the old painter Giovanetti, his wife Renata, and a young foreign woman the Giovanettis have brought with them from town. Normally he would be at the office at this hour, but it is the Feast of the Ascension “and here he was pinned to a sofa among the women and the aged, like someone left behind during a war.” With the one word pinned, Hazzard conjures Eliot and all of Prufrock’s existential ennui.

I reach for it when I am stuck, scared, or bored, when I am at loose ends or bound up tight. I raise it like a sacred text, let it fall open where it will.

He complains to himself that his sister is not doing tea properly (there is no actual tea), ashamed that Italians don’t know how to entertain in their houses in the late afternoon, “so one is likely to be confronted, as on this afternoon, with half a bottle of sweet vermouth and a plateful of stale macaroons.” He doesn’t acknowledge—and in fact may not know it himself—that he is seeing this afternoon already through eyes of the foreigner, Sophie, whom he first assumed was the archetypal Englishwoman until he learns she’s half Italian and whom, either way, he finds unremarkable. Still, she inspires a sort of fresh perspective for him, and for the first time he really sees the old painter, a man he’s known all his life.

Old Giovanetti, sitting upright in a plush armchair, clasped both his hands over the knob of a black walking stick that was planted at his feet. In this attitude he was like an old crusader, his noble face and his long, lean body and his stillness conveying some figure on a perpendicular tomb.

Tancredi recognizes that his own paunch and bland handsomeness puts him at a physical disadvantage in contrast with the old man’s distinguished vitality. But, he thinks, handing Sophie a glass of wine, “she was nothing extraordinary, either.” Yet, though they haven’t spoken, she is already altering his experience of his own body. And he does not like it. “No, she was nothing special,” he tells himself again and critiques her appearance, the prim striped dress with a high collar and sleeves nearly to the wrist, though he remembers that the day before, when he’d seen her in town, “he had noticed the shape of her shoulders and the prominent bones below her throat.”

Hazzard loads her objects with great emotional weight and wields them like burning torches to tell her tale.

It is Sophie who breaks their silence. “What is the fountain?” she asks him. And so it begins. In fits and starts, lurches and pauses, they start to speak to each other. In one of those stunning falcon dives, Sophie tells him she knows the Giovantettis through their daughter Sibilla, who was a friend of hers at college. Tancredi knows her, too:

It happened that he had at one time been rather in love with this same Sibilla and was both pleased and sorry to be reminded of her now. They had carried on a long flirtation, quite unsuspected by his wife; after Sibilla’s marriage they kept vaguely in touch. And when she went to Mogadiscio he sent her letters, to which she never replied; he wondered if she had even received them. (These letters had, in fact, reached Sibilla and greatly amused her, bored as she was on that splendid, lonely coast of East Africa. She had written a long and indiscreet reply, which the Somali houseboy had thrown away instead of posting, having first removed the stamp for resale.) The thought of Sibilla—who was more beautiful than this girl—and of his unanswered letters now began to depress Tancredi. In his heart he sighed. What an afternoon.

The swoop to Sibilla in Mogadiscio is so sudden and thrilling for the reader. We haven’t even had access yet to Sophie’s thoughts and here we’ve travelled to Somalia and back in the course of a parenthetical. Their conversation stalls and he ends up telling her a story about his university days and she, finding an inconsistency, teases him:

“I thought you were a romantic.”

“Oh, he cried, pleased with her again. “Is this to be one of those days when everything you say is remembered and used against you?”

“One of those days?” She looked back at him over the glass, still smiling. “I shouldn’t have thought there was any other kind of day.”

I love this moment, when their banter begins, when their affection ignites. He has underestimated her. He has been judging her appearance, her foreignness, her femaleness, but she—her mind, her character, her self—prevails.

When they go to the fountain, they go alone—the old man cannot make it down the steps and calls out to Sophie “Refresh my memory”—and as they walk through the garden Tancredi tells her that old Giovantetti in his day was very “charming to women” and Sophie replies, “All Italians are charming to women.” I know you and I know just how far to trust you, she seems to be telling him, and his only defense is to quote Petrarch. They reach the fountain and Sophie is moved by its beauty. She runs her fingers through the water, her bracelet slips off, and she rolls up a sleeve to get it.

He thought, as he watched her, that in all his life he had never seen a more seductive thing than the unconsidered gesture with which he she folded back her sleeve. …He was amazed too by the magnitude of his own response, which gave her gesture real consequence. Although he had spoken to her earlier of his romantic temperament, he was as shaken by this pang of authentic sentiment as if he had encountered a friend totally unchanged after an absence of twenty years.

He recalled how the old man had said to her, at the top of the steps: “Refresh my memory.”

Memory and desire. Eliot again. Tancredi, the aging, unserious flirt, is falling in real love.

For Sophie it happens more slowly. She has unexplained commitments back in England. A fiancé? A husband? Children? In a postcard she writes “I miss you all.” But we never learn more. His feelings for her are inconvenient; she does not take them seriously. When we first have access to her thoughts, at the end of the second chapter, they are alone in another garden, listening to a nightingale. He is deciding when to take her hand, but she is not thinking of him at all. She is straining to remember the first line of Keats’ ode.

In the end it is language that overpowers her. She has rebuffed him, he has gone away for a few days, and she receives a letter from him. She opens it at lunch and leaves it on the table and a line keeps catching her eye. He writes that he could explain himself if she weren’t absent, “if you were made of flesh instead of air.” When Sophie looks at it again we are given the more powerful (to me anyway, because of the more poetic syntax and the very sexy congiuntivo imperfetto) Italian: “se invece che d’aria tu fossi di carne.” This one line is Sophie’s undoing.

It is not surprising, given Hazzard’s mastery, that words would be the ultimate conduit of feeling, the final surge that overwhelms her and affects the reader (this reader, at any rate) so deeply. The fountain, the bracelet, the letter, the magnificent use of a pair of his gloves at the end of the novel—Hazzard loads her objects with great emotional weight and wields them like burning torches to tell her tale. In the garden, as the nightingale is still singing, Sophie finally does remember Keats’ first line: “‘My heart aches…’”

By then end so does ours.

_____________________________________________________________

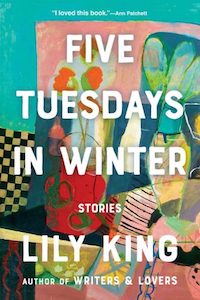

Lily King’s Five Tuesdays in Winter is available now via Grove Atlantic.

Lily King

Lily King’s novels include The Pleasing Hour, The English Teacher, and Father of the Rain. Her most recent, Euphoria, has won numerous awards and was named one of the ten best books of 2014 by the New York Times Book Review, is being translated into numerous languages, and will be a feature film.