Every Foodie Has an

Origin Story

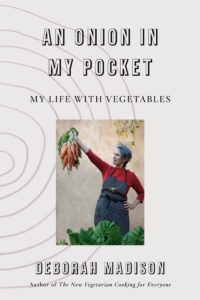

Deborah Madison: Suitcases of Quince and an Onion in Every Pocket

If there are not onions in my pockets or my purse, maybe there are shallots, or some amaranth leaves, or seeds collected from the garden, or something else food related. Once there was a four-foot-long gopher snake in my purse—safekeeping for the walk home. These snakes do lower the numbers of those garden pests. But there was a day when there actually was an onion in my pocket because I had been cooking with my pal Dan, and I had brought the onions that we needed for a pizza. There was one left over. In Spanish class I pulled out the extra onion and put it on the desk so I could find my notes and pens—also crammed into my pockets that day. People started to laugh. To me it was utterly normal.

That’s partially what it means to be a food person—that it is normal to find an onion in your pocket. Or that you fly home with quarts of fragrant berries on your lap, or you stuff a bag of superlong stalks of late-summer rhubarb into the overhead. It’s likely that when a friend visits you in your new desert home she arrives with egg cartons in her suitcase—a ripe fig nestled into each little depression—or that another friend arrives with an extra suitcase filled with quince. Food swirls around us. We reach out for some of it; other times we toss something good into the swirl for others to enjoy. It’s the forever potlatch of gift and exchange.

I didn’t always know I’d be so involved with food and I’ve long tried to piece together when it first happened, when food became something good and compelling. I think it was when I was sixteen. My parents had gone to Europe for a sabbatical and farmed each of their four kids out to another family. I got to live with a couple who did not have children, who had lived many times in France, who loved food and knew how to cook. Living with them I discovered that food could be good every night of the week. Given my parents’ uneven temperaments and my mother’s frugality I had no idea that this could be so. But it was and it was miraculous. Cheese soufflés, chicken poached in wine with mushrooms and cream, salads from the garden—it was all so delicious and it was all new to me. When my parents returned from their trip, they remarked on my new round face, evidence that butter and cream, predinner gin and tonics, and the much better wines we drank—the plenty of very good food and drink, in short—had had an effect. When people ask me when I became interested in food, I tell them it was when I discovered that food could taste good. Every night of the week. These meals did change my life.

The man in my temporary household was, like my father, a botanist; only his specialty was alliums, not grass. Like all botanists and food people I have known, his eyes were open to all kinds of possibilities, especially culinary ones. Over a long weekend we took a trip to Mount Lassen. Once there and settled into our motel, we set out on a hike with the intention of spending the day on the trail. Shortly into our walk, I noticed some funny-looking things poking out of the ground. I asked what they were and the botanist and his wife both responded with ecstatic shouts: “Morels! They’re morels!” We immediately filled our hats with them, abandoned the walk, and drove into town in search of butter and cream.

I didn’t always know I’d be so involved with food and I’ve long tried to piece together when it first happened, when food became something good and compelling.

We simmered the morels in cream and piled them on buttered toast for lunch. They were magnificent and they taught me my first food rule: Break your plans in the face of something wonderful and utterly unexpected, like morels. Let this food rule take over and push you here and there as it will. You will at least come away with a memory. This event is decades old, but it remains a vivid memory.

Despite this introduction to the pleasures of the table and my excitement about food tasting good, I didn’t act right away. The thought “I want to be a chef” never occurred to me. Instead, I finished high school, went to college, dropped out, got back in, changed universities, graduated, got a job, went to Japan, then became a practicing, even ordained, Buddhist for about twenty years. It wasn’t until I became a Zen student that I became interested in cooking and started to cook in earnest. It’s supposed to be so austere, that Zen life, but people still have to eat and some- one has to cook. That person became me in 1970.

I’ve cooked for a long time: in the San Francisco Zen Center; at our monastery at Tassajara; at our farm, Green Gulch; at Alice Waters’s restaurant in Berkeley, Chez Panisse; at Greens, the vegetarian restaurant I opened in San Francisco; at the American Academy in Rome; at Café Escalera in Santa Fe; and at home—when I finally got one. (I lived in community until I was forty.) At some point I decided to look back to find out what matters when it comes to food, and that’s what An Onion in My Pocket is about.

__________________________________

From An Onion In My Pocket by Deborah Madison. Copyright © 2020 by Deborah Madison. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Deborah Madison

Deborah Madison is the award-winning author of fourteen cookbooks, including The New Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone and Vegetable Literacy. Her books have received four James Beard Foundation awards and five awards from the IACP; in 2016 she was inducted into the James Beard Foundation Cookbook Hall of Fame. She lives in New Mexico.