Even When Records Fall Short, Black History Must Be Told

Morgan Jerkins on the Story of Her Family

I grew up with my family speaking through circumlocution. I knew other Black families who didn’t speak about the past or present due to trauma. These omissions were inspiration for writing a book in the first place. I traveled across the country to construct these bridges amongst Black communities in spite of time and distance.

Eventually, this journey took me to my great-great-great-great grandmother Carrie, whose relationship with my great grandfather—and her life in general—was filled with many holes. Her full name didn’t appear anywhere, not even in one of her grandchildren’s biographies. It took me a year to potentially find her origins, alongside one of my cousins, who had been documenting our family for decades. But to this day, we cannot be 100 percent sure.

I have both a Bachelor’s and Master’s so I’ve been trained to always find proof and contextualize well. I once had a white roommate who continuously undermined my experiences and sensations as a Black woman by blurting out that I needed to cite my sources and give my proof; often, I’d be stunned to silence. Then I had an epiphany: this silence is intergenerational. We don’t think that people will believe the magnitude of our experiences. When I did research for my book, I thought that the horror with which my interviewees described their histories would be almost too damning to document. Some of them risked their lives to divulge details to me about what was going on in their communities.

Truth be told, I feared no one—not my publisher, loved ones, or readers—would believe me. Some days, I didn’t want to believe the intensity and devastation of what I’d been told either. I wanted the disempowered to provide papers when such documentation belongs to the powerful.

Eurocentrism tells us that written history takes precedence over any other form of narrative. Those who are able to detail their experiences and events on paper are given more credibility than those who do not or cannot. There is a history of what happens when Black stories are documented, and therefore claimed, by others. In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) sent out-of-work scholars and students to the south to collect the stories of former slaves, but their methods were blatantly sexist: Women were asked about their domestic work and men were asked about their jobs and any adventurous pursuits. Oral histories were always, in a sense, “available,” but scholars generally rejected them because the written word was considered the objective, unwavering, and permanent truth.

One of the pioneers of promoting the invaluableness of all kinds of histories—both oral and documented—in African-American life was Zora Neale Hurston. As a folklorist who traveled from the American South to Jamaica and Haiti, she collected folk tales and stories surrounding voodoo. She called folklore itself “the boiled down juice of human living … In folklore, as in everything else that people create, the world, as in everything else that people create, the world is a great, big, old serving platter, and all the local places are like eating plates. Whatever is on that plate must come out of the platter, but each plate has its own flavor of its own to suit themselves on the plate. And this local flavor is what is known as originality.” As Hurston was preparing her draft of Mules and Men, an autoethnography on her travels in Eatonville and Polk County, Florida and New Orleans, she told Franz Boas, an anthropologist and her mentor from Columbia University, that her findings were not conventionally scientific—they were not based on “hard facts” but nevertheless, the stories were true. For Hurston, folklore was always evolving and her positioning as a subject in the midst of her field work revolutionized not only anthropology but also representation of African-American life.

There was both documentation and lore throughout my recordings, and the lore was just as real as the “evidence.”

Like Hurston, I left the Big Apple to travel to the deep South because I had to insert myself into these communities in order to do them justice. My goal was not to reconcile the strength of my subjects’ stories with that of the power vested in white dominated institutions, because that may not be possible. My goal was to listen and document, to make others aware of the realities and painful legacies that lurk beyond every corner. I had to break my own thinking of what can be considered the “truth,” continue to be the messenger, and tell what I heard and saw. In fact, I’d argue to say that multiple truths can exist at once.

When one wants to write about the African-American past, one has to think imaginatively. One has to imagine millions of people whose identities had been taken and manipulated since first appearing on the shore of the colonies. One has to imagine how literacy meant death for us. One has to imagine how remaining secretive or finding subversive ways to communicate was about survival. As I sat in front of my hundreds of pages of transcriptions and hours upon hours of interviews, I knew I had a treasure trove. There was both documentation and lore throughout my recordings, and the lore was just as real as the “evidence.”

So I began to ask myself questions. If I couldn’t find documentation of a subject’s family specifically, could I substantiate their stories of loss in the form of land theft or cultural loss with similar stories of those in the same region? Yes. Could I detail the history of said region that gave rise to these devastations? Indeed I could. When I traveled, I could see the erasure of Black communities in the physical landscapes because often there weren’t any monuments or historical markers that honored their presences and labor. I had to trust myself as a Black woman and not wait for anyone to validate my immediate observations. As far as tracing my family, I read in between and around the lines of what my relatives said and what documents stated. I researched locations, dates, and blended family trees to arrive at the conclusion as to why so much had been hidden.

There were many revisions along the way, as books tend to have. But I’ll admit that my revisions centered on the fact that while I tried to act as a distant observer in its earliest drafts, I couldn’t. I was involved as a Black American and a descendant of those who migrated and hid for safety.

The closer I moved towards my subjects and their homelands, the more intimate the book became. The more I researched, the more I knew what was at stake. I knew methodological data was not enough. To detail Black living and death, I needed a gumbo of tools: journals, articles, scholarly interviews, oral history, and personal history. I didn’t ignore the omissions—I exposed them. I confessed my frustration and I spoke of the foundation for these omissions. Then I kept going because I had to.

I wasn’t a distant observer. I was just as much of a character too, for when I found other subjects, I found myself.

__________________________________

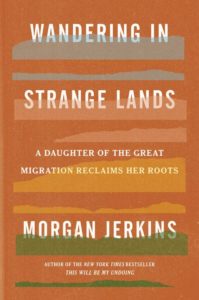

Wandering in Strange Lands: A Daughter of the Great Migration Reclaims Her Roots by Morgan Jerkins is available via Harper.

Morgan Jerkins

Morgan Jerkins is the New York Times bestselling author of This Will Be My Undoing, Wandering In Strange Lands, and Caul Baby.