Eve and Joan: Exploring the Tumultuous Friendship of LA’s Literary Ladies

Lili Anolik on the Irresistible Draw of Eve Babitz and Joan Didion, Two Iconic Chroniclers of California

My book on Eve Babitz, Hollywood’s Eve, came out in 2019. Writing it was my way of driving a stake through her heart.

It wasn’t that I didn’t love her. It was that I loved her too much. I’d been in her thrall for nine years. Ever since I bought a used copy of Slow Days, Fast Company from a third-party seller on Amazon back in 2010. My appetite for details about her was gnawing, unappeasable. Her sister, her cousin, her old lovers and rivals and companions, were now my friends. And when I wasn’t on the phone with her, I was on the phone with them discussing her: her character and past; her motivations, both opaque and lucid; the various plot holes in which her narrative abounded.

My preoccupation was unbalanced, fetishistic. Sick is what it was. And it made me sick—anxious and grasping and, in some obscure yet vital sense, self-abandoned. I needed to stop living her life, reclaim my own. I needed to get violent.

That’s what was going on with Hollywood’s Eve, which, by the way, started out a different book entirely—a book about L.A. from the mid-twentieth century to the early twenty-first, Eve a key figure in it though one among many. And then Eve took over. (To be clear, I don’t mean Eve the person, who was, by the time I knew her, an Eve made of shadow, there but not. I mean Eve the energy, Eve the spirit.) Took over with my blessing. The idea was to give in to my obsession, submit to it, let it derange me, so that, by the end, either it would be gone or I would. A kind of auto-exorcism.

Eve was talking to Joan the way you talk to someone who’s burrowed deep under your skin, whose skin you’re trying to burrow deep under.

As plans go, a risky one. It worked, though. After publication, I no longer felt beset or crazed. Was able to tend to my growing family. (When I met Eve, I was pregnant with my first son. I’d have my second two years later.) Pursue new interests and projects: an oral history of the writers of Bennington College, class of 1986, for Esquire; a podcast on former adult star Traci Lords for a company called Cadence 13. To, in short, think about something—someone—else.

I was saved.

*

It was on New Year’s Day 2021 that Eve’s sister, Mirandi, FaceTimed me. Mirandi and I usually spoke every week but had skipped the last few: holiday madness. And our talk was happy, empty—what we said less important than the act of saying.

We were twenty minutes into the call. She was telling me about Eve and Eve’s move the month before to an assisted living facility in Westwood, the one Eve had resisted for years.

“Eve loves it,” Mirandi said. Immediately she amended this statement: “Well, Eve doesn’t hate it.”

I was only half listening. Archie, my younger boy, had entered the room and was tugging on my arm. He wanted to play. Realizing I was nodding even though Mirandi hadn’t said anything that required a nod, I forced my head to stop. I bugged my eyes at Archie—a warning—and said to Mirandi, “What does she not-hate about it?”

“There’s somebody to clean her room for one thing. And cook.”

“It’s like living in a fancy hotel. Big surprise she’s not bitching.” I ignored the look Archie was giving me for bitching, then decided not to. “Sorry,” I mouthed.

Mirandi laughed. “Yeah, one she never has to check out of.”

Pulling Archie onto my lap, I changed my tone, made it serious. “Is there anything she needs? I mean, that I can get her?”

Mirandi to Archie: “Well, hello there, young man.” To me: “No, I think she has everything.”

“Sure?”

Mirandi raised a finger. “She told me to tell you to send P.G. Wodehouse.”

“Did she say which books?”

“No.”

“I’ll just send a bunch. Text me her address when we get off the phone.”

Mirandi said she would, then launched into a convoluted story about the difficulty of closing on Eve’s apartment. Eve, it seemed, hadn’t paid her mortgage for more than a year. Wells Fargo had sold the note to another company, which had in turn sold it to yet another company, and that company was now demanding Mirandi produce all manner of oddball documents. Plus, the escrow agent, a “darling Jewish Persian,” was, all of a sudden, acting less darling, and Mirandi suspected alcoholism.

Archie was getting restless in my lap. I waited for Mirandi to pause, take a breath, so I could break in, let her know I had to go. Only she broke in first, interrupting herself to say, “Oh, I meant to tell you. I was cleaning out Evie’s closets—mostly throwing things away—but at the back of one, underneath a whole load of crap, I found these boxes. Mother must’ve packed them when Evie left Wilton Place all the way back in—” She stopped, her lips moving in silent calculation.

“2001,” I supplied automatically.

“That’s right. Evie must’ve forgot about them or she never would’ve left them alone. Well, I opened one.” Mirandi leaned into the screen confidentially. “You’re not going to believe what’s in it. Letters. Lots of letters—to Eve, from Eve, and…”

Mirandi’s words had just touched my consciousness, barely grazed it, when I felt my mouth go dry, a queasy flutter in the pit of my stomach. A voice inside my head whispered, She’s back.

Archie began swinging his legs, a heel connecting painfully with my shin. I pushed him roughly off my lap. He whimpered—a distant buzz.

“Everything all right, honey?” Mirandi said.

I rubbed my eyes, the eyes that used to be mine, and nodded. “Sorry, yes. You were saying about the boxes?”

Mirandi talked, but I couldn’t hear a thing she said. Fear and dread were beating in my blood along with my heart, a wet, heavy pump pump pump.

*

Those boxes.

I kept waiting for Mirandi to ask me to fly to L.A., go through them with her. But weeks passed, and she didn’t. And so, as Eve had shoved them to the back of her closet, I shoved them to the back of my mind. And that’s where they stayed for almost a year.

In that almost year, I got things done: I turned the oral history of the writers of Bennington College into a podcast, sold a proposal for a book on the same subject to Scribner, wrote various pieces for various magazines. I took my sons to school, my dog to the park, my husband for granted. Occasionally I cleaned. Less occasionally I cooked. I was never not busy.

And then, a few days before Christmas 2021, Eve, who’d been dying gradually, died suddenly.

Her memorial was held in mid-January. The ceremony ended, and Mirandi pulled me aside. Lowering her mask—Covid was still raging—she asked if I’d go with her to the Huntington Library while I was in town. (The Huntington had acquired Eve’s archives, the boxes included, the boxes principally.) Unable to think of a polite way of saying no, I said yes.

*

The next morning, I took an Uber to the Huntington, just outside Pasadena in San Marino. I arrived before Mirandi. This was intentional. I didn’t know what kind of reaction I was going to have and wanted to have it in private.

My driver dropped me at the wrought-iron gates. I walked down a winding path, through the grounds—spectacular, though I scarcely noticed—to the research library. At reception, I slipped off my mask. The guard held up my ID to my face to make sure the two matched. Rubber gloves were given to me, along with the solemn instruction not to touch photographs or negatives bare-handed. I was then led into a large, silent room full of tables. I sat at one in the back, playing with the fingers of the gloves and waiting for the man behind the desk to put down his newspaper, bring over the first box. Above my head a wall clock softly ticked. I listened to it, listened to time, and tried to control my caroming thoughts.

The boxes would turn out to be no big thing, I told myself. Mirandi was doubtless overvaluing their contents. “Lots of letters” probably meant a few faded postcards mixed with dry-cleaning stubs, unpaid bills, junkmail flyers, and takeout menus from restaurants that had long since gone under. Eve, after all, was the slob of the world. Hadn’t Mirandi found Ed Ruscha’s Eve drawing—worth a couple hundred thousand, minimum—on the filth-covered floor of her bedroom, a giant footprint in the middle of it, for God’s sake? Maybe I came here for nothing. Maybe she really was done with me. Maybe I’d be spared.

At last, the man slid the box onto the tabletop. I smiled my thanks. He didn’t smile back, and several seconds passed before I understood why: he couldn’t see my smile; it was behind my mask.

The man returned to his desk. I waited for him to reopen his newspaper—a screen between us—then reached for the box. With a trembling hand I lifted the lid.

The first item I pulled out, a letter. It was a page and a half long, typewritten with handwritten corrections, from Eve to “Dear Joan.” Dear Joan. I stared at those two words—uncomprehended, incomprehensible—until it dawned on me what they meant: “Dear Joan” was that Joan, the Joan.

Joan Didion.

Excitement rose in my throat like bile. Phrases began leaping out at me: “burning babies,” “foggy brains,” “ill bred, drooling, uninvited Art.” I squeezed my eyes shut. When I opened them, I dragged them to the first line and started to read, making myself go slow.

Dear Joan:

This morning I telephoned and wanted you to read A Room of One’s Own, because it struck me because I was thinking about what you said about Quintana and the sprinklers and I was again remembering this shimmer of accuracy that Virginia Woolf got in The Waves (which you say you haven’t read).

It’s so hard to get certain things together and especially you and VW because you’re mad at her about her diaries. It’s entirely about you that you can’t stand her diaries. It goes with Sacramento. Maybe it’s better that you stay with Sacramento and hate diaries and ignore the fact that every morning when you eye the breakfast table uneasily waiting to get away, back to your typewriter, maybe it’s better that you examine your life in every way except the main one which Sacramento would brush aside but which V. Woolf kept blabbing on about. Maybe it’s about you and Sacramento that you feel it’s undignified, not crickett [sic] and bad form to let Art be one of the variables. Art, my God, Joan, I’m embarrassed to mention it in front of you, you know, but you mentioned burning babies in locked cars so I can mention Art.

You said that the only thing you like to do was write. Just think if it were 200 years ago and the only thing you liked to do was write. I know I’m not making sense, but the thing beyond what your article on the women’s movement was about was what A Room of One’s Own is about. The whole women’s thing that is going on now is so stark and obscene most of the time that no wonder one recoils in horror. But for a long, long, long time women didn’t have any money and didn’t have any time and were considered unfeminine if they shone like you do, Joan.

Just think, Joan, if you were five feet eleven and wrote like you do and stuff—people’d judge you differently and your work, they’d invent reasons…Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening? Would the balance of power between you and John have collapsed long ago if it weren’t that he regards you a lot of the time as a child so it’s all right that you are famous? And you yourself keep making it more all right because you are always referring to your size. And so what you do, Joan, is live in the pioneer days, a brave survivor of the Donner Pass, putting up the preserves and down the women’s movement and acting as though Art wasn’t in the house and wishing you could go write.

It embarrasses me that you don’t read Virginia Woolf. I feel as though you think she’s a “woman’s novelist” and that only foggy brains could like her and that you, sharp, accurate journalist, you would never join the ranks of people who sogged around in The Waves. You prefer to be with the boys snickering at the silly women and writing accurate prose about Maria who had everything but Art. Vulgar, ill bred, drooling, uninvited Art. It’s the only thing that’s real other than murder, I sometimes think—or death. Art’s the fun part, at least for me. It’s the salvation.

When I reached the last line, I took a deep breath, only to find I couldn’t. My breath refused to catch, turn over. All I could do was breathe rapidly, shallowly, skimming off the top of my lungs.

A lovers’ quarrel. That’s what this letter was. The tone that alternated between j’accuse and groveling, the recriminations and resentments hurled like thunderbolts, the flashes of rage, despair, impatience, contempt. Eve was talking to Joan the way you talk to someone who’s burrowed deep under your skin, whose skin you’re trying to burrow deep under.

I wouldn’t be telling just Eve’s story. I’d be telling Joan’s story, too. Joan, Eve’s opposite and double, completing and revealing Eve as Eve completed and revealed her.

I was hearing a conversation I wasn’t supposed to hear, and my eyes listened ravenously. That I was behaving like a sneak and a snoop, a Peeping Tom peering through the keyhole, an eavesdropper crouched beneath the window, didn’t escape my attention. And I felt guilty about it, I did. But I couldn’t stop. Something profound was being revealed to me.

It wasn’t news that Joan and Eve were part of the same scene in the late sixties and early seventies. (The Franklin Avenue scene was what I called this scene in my head because it centered on a ramshackle house in a gone-to-seed section of Hollywood where Joan lived with her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, and their adopted daughter, Quintana: 7406 Franklin Avenue.) Nor was it news that Joan had done Eve a good turn with Rolling Stone. (Joan recommended a piece Eve had written on the girls of Hollywood High to the magazine, and the magazine took it. Eve’s first byline.) What was news: that Eve’s feelings for Joan were urgent enough, passionate enough, to compel her to write a letter so blatantly aggrieved.

And so subtly vicious. When she refers to Joan as “you, sharp, accurate journalist,” she means to draw blood. The letter was written in 1972, by which time Joan had published three books, two of them novels, Run River and Play It as It Lays, and was about to start a third, A Book of Common Prayer. That she thought of her novels as her “real” work, her journalism as what she did in between novels, a way of keeping her hand in, there’s little doubt. For Eve to call her a journalist was thus a whopping put-down.

I knew Eve so well. But, after reading this letter, I realized that I didn’t know Eve at all. Or, more accurately, that I knew the wrong Eve.

When I was writing Hollywood’s Eve, I had full access to her. Since 2012, she’d taken my calls day and night, answered any question I cared to ask. I didn’t, though, have full access to Eve of, say, 1972; that is, Past Eve. And Past Eve was the Eve I wanted. Past Eve could, of course, be found in Eve’s memoir-like books. Only not really, not actually. In converting life into art, Eve had removed herself from the life. In other words, the I in her stories wasn’t quite the I telling her stories, even if all autobiographical writing is poised on the premise that the two are one and the same, a single coherent entity. The letter to Joan proved that they weren’t coherent. The I voice in it was sharper, darker, more devastated, less casual.

And, besides, 2012-and-beyond Eve might have been honest about her life, but she was—again—at a remove from it. The years had put her at a remove. She’d grown detached from her earlier self. When I met her, she was old and, in her way, at peace. In this letter, however, she was young and in a fury. Was preserved in the chaos and confusion, turbulence and tension, of the ongoing moment. Time hadn’t yet made her impervious. Or healed her wounds. They were raw, bloody, and she was picking at them so they were rawer, bloodier still.

Then there was the third obstacle: her charm. In 2019, New York Review Books Classics released a collection of her best uncollected pieces, including “I Used to Be Charming,” about the 1997 fire that nearly burned her alive, leaving her in too much pain for social graces. But that title was baloney. Even at the end, when she’d lost her health, mind, and marbles, she still had her charm, and it wouldn’t allow her to admit to anger or unhappiness. (Charm—maintaining it, spinning it—was for Eve a matter of honor, I think.) And it was yet another barrier, yet another remove.

I stood up from the table abruptly, hitting my chair with the backs of my knees, sending it skittering. I left the room, then the building. Once outside, in the privacy of the gardens, I tore off my mask and began sucking in long drafts of cool air.

It was back. My love for Eve’s astonishing, reckless, wholly original personality and talent. I knew immediately and with utter certainty that the story I’d been planning to tell, had accepted money to tell—Bennington Class of ’86—would have to wait. Instead, I’d tell Eve’s story again. Except this time I’d tell it differently. Better. Because I wouldn’t be telling just Eve’s story. I’d be telling Joan’s story, too. Joan, Eve’s opposite and double, completing and revealing Eve as Eve completed and revealed her. (What else I realized after reading the letter: that I also knew the wrong Joan. Or, rather, that I knew only the Joan that Joan wanted me to know. I’d always taken Joan at her persona, which I’d never, until this moment, noticed was one.) And because I wouldn’t be telling Eve’s story alone. The telling would be a joint effort, Eve no longer merely my subject but my collaborator, my colluder, my accomplice, as well. I had her letters now, hundreds of them. And those uncanny pieces of paper, so intimate you didn’t read them so much as breathe them, made her more alive than ever, even if she was, technically speaking, dead.

She and I would write this new book together.

I hooked the straps of my mask back over my ears. As I looked up, I spotted Mirandi in front of the library. She was waving at me. I returned the wave and started to make my way out of the gardens, first slowly, then quickly, then more quickly still. Like I was running from something and to something at the same time.

It was the horror of losing myself in Eve again.

It was the thrill of losing myself in Eve again.

I couldn’t get away fast enough.

I could hardly wait.

__________________________________

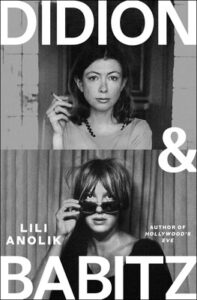

From Didion and Babitz by Lili Anolik. Copyright © 2024. Available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Lili Anolik

Lili Anolik is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and a writer at large for Air Mail. Her last book, the L.A. Times bestseller Hollywood's Eve, was also published by Scribner. Her last podcast, Once Upon a Time…at Bennington College, was produced by Cadence13. In 2024, she was a finalist for the National Magazine Award for profile writing. She lives in New York City with her husband and two sons.