Erica Berry on the Polyamorous Intimacy of Reader, Author, and Audiobook Narrator

"It had not occurred to me that the thing I was drawn to was what I felt most lacking in myself: an even-keeled authority."

I always imagined, that, given the choice, I would read my own audiobook. I had heard memoirs often sounded best in the author’s throat—something about the familiar tang of the hardship unspooled. But had I written a memoir? A bookseller acquaintance asked me that a year before the publication of my debut, and I wasn’t sure what to say.

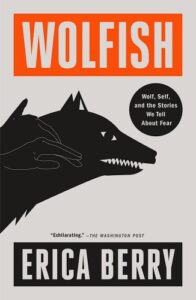

There’s a big strand of me, I said, before explaining there were also strands of history and folklore, of cultural criticism and science. Wolfish was a braid of source material, weaving my life and the path of a wandering wolf while examining of the symbolic and real wolves that surround us both.

Thinking about how the book moved between research and self made me question my fantasy of reading it aloud. I had decided to detail some of my most intimate experiences with fear on the page, but I still got nauseous imagining people reading them. Judgement was inevitable. I could not square my desire to write my truth with my desire to be liked. Would these scenes be more palatable if bundled in the cadence of my own emotion, or would my voice create another reason for someone to complain?

Her work was about my words, but my words only existed through her.

I wish I could say I decided not to read the audiobook because it didn’t interest me, but that would be a lie. I didn’t read because I was afraid. When I told my editor I had decided to take up the publisher’s offer of a professional, I thought I was signing up for a boost of talent. I hadn’t realized that inviting someone to crawl into my sentences would change my relationship with my past, my words, and—somewhere along the way—deliver a friend.

*

The first time I heard Lessa Lamb’s voice, it was in a line-up of auditions sent to me by the Macmillan audio team. The one I initially gravitated toward was calm and low in pitch, but everyone I played it for disagreed. The older voice isn’t quite right, a friend said. It doesn’t have your youthful enthusiasm.

It had not occurred to me that the thing I was drawn to was what I felt most lacking in myself: an even-keeled authority, the voice of someone reading a bedtime story, not living it. I could not escape my voice, even when it was narrated in the lips of another reader. And so we landed on Lessa. Her voice was bright and smooth. I felt like I was picking a video-game character: her voice would make me strong.

Months later, when her narration was recognized with an Earphones Award from Audiofile Magazine, the write-up described her reading as a fine-tuned balance of enthusiasm and empathy, “inhabit[ing] the youthful sound and elegant style.” The thrill I felt for her was ribboned with pride and disembodiment. Her work was about my words, but my words only existed through her. Where did my voice end and Lessa’s begin?

*

During the days Lessa was recording, I tried not to think of her. I felt naked knowing a stranger was spending days of her life sifting my words. I know of a photographer who got permission to go into other people’s houses, put on their clothes, and take a self-portrait. Who did she capture in those images? Not quite herself, but not quite the original occupant either. I felt like Lessa was in my house, staring at the dust bunnies, wondering why I’d kept this or that shirt in the closet. I thought about Lessa judging me perhaps because it was easier than imagining her becoming me. It had not yet sunk in that listeners would meet a hybrid narrator: part me, part her.

The first time I knew I wanted to talk to Lessa directly was when I learned that her search for Nez Perce pronunciations had led her to conversations with tribal members on a language committee, the trading of audio files, and eventually, a suggestion for me to make to alter a few words. I was overwhelmed with gratitude, and humbled by my own ignorance—not only of the correction, but of the time and care she had invested sleuthing it out.

Releasing a book was teaching me how much of its creation depends on waves of invisible labor, not only assistants and interns, but the workers who make and deliver the books. Why had it never occurred to me to consider the unseen work of audiobook narrators and producers too? Lessa researched my book for 45 hours, at one point getting pronunciation advice from Facebook.

The first time Lessa wanted to talk to me directly was when, mid-read, she realized we had both grown up in the Pacific Northwest, then traveled and lived around the world before coming home. “You have to put me in touch with her, we have so much to talk about,” she recalled saying to the producer. “I just knew we’d get along.”

Around that time, my words were taking flight. Leaving the neat rows in her Android tablet and entering her house, 150 miles north of me. She recorded in a double-walled foam-lined studio that sat, like a hand-built three-dimensional closet, in the middle of her office. When, months later, she showed me this set-up on Zoom, I felt a strange jealousy. My book already knew the room so well.

*

The first time I received a link to the audiobook, I did my best to ignore it. I did not want to hear my words aloud. My pre-publication months were spent in nauseous insecurity, unsure how I, a body, would coexist in the world beside the thoughts I was now sharing. If a book is two dimensional, an audiobook is something else. Not quite 3D, but 2.5—enough to fill a room. I was scared of it.

I was touring the east coast when I finally summoned the courage to listen. Large parts of the book took place in Oregon, a home that now felt very far away. Clicking into the track, a young woman’s voice entered the beige hotel room. She was full of doubt, trying to weigh the anxiety she felt beside a man on the train. Somewhere in my chest, I felt a strange squirm of tenderness. I was not used to feeling this when encountering my own work. My voice of self-criticism is so loud. But hearing my life in another person’s voice, I ached. I wanted to tell the woman to trust her instinct. I wanted to tell her it was going to be okay.

The narrator of a first-person book is not the author, she is a version of her, a core-sample of a life rolled out for a story. Listening to Lessa was helping me put necessary distance between the self I had pinned on the page. The me I wrote into Wolfish was a mosaic of my experiences and feelings, each one a shard from something bigger—a reminder of how much of my life was still private. Hearing Lessa voice the scenes from my life reminded me that they were no longer mine alone. I had, by putting them in a book, cased them in amber, handed them out. Readers would pick them up and have their own experiences with them. That wasn’t just okay—that was the point.

Around this time, Lessa and I became friends on Instagram. I admired her pitbull-shepherd, Sultan, and her purple pixie cut. She sent me a photo of a fleecy wolf-print bathrobe she had found while shopping. I sent her screenshots of messages I received from readers who resonated with her narration. We exchanged numbers. We got on Zoom. I told her that, more than once, someone had asked if we selected her to read a wolf book because her surname was Lamb. She laughed. So you get that too.

Listening to Lessa was helping me put necessary distance between the self I had pinned on the page.

“The goal of every narrator is to release the author’s words vocally in such a way that the core of what the author is trying to convey to their audience is automatic,” Lessa told me. She had tried to help land my vision in people’s ears. In part because she often narrated romance books, she was acutely aware of what a narrator could kindle. “When you’re reading a book with your eyes, you have an intimate relationship with the author and what the inside of their brain looks like,” she said. “When you add a narrator to that process, you now have this almost polyamorous relationship with the writer and the listener.”

Lessa has a degree in psychology and has done sex and relationship coaching; she is also polyamorous. As a narrator, she thinks often about the responsibilities and power dynamics of her job. “I’m facilitating intimacy between you and the listener,” she said. “I have to kind of both step out of and more deeply into myself.” Her task, she said, was to interpret my emotions and motivations on the page. “I’m doing this with my entire being.”

*

When Kate Zambreno and her Swedish translator Helena Fagertun write about their relationship in two short essays for Astra magazine, both of them describe the anxiety of meeting as two bodies off the page. “I knew I needed to play the part of the author of the books she had translated,” writes Zambreno, “and I wonder whether my presence was disappointing for her, or whether I seemed enough like myself, or the version of myself that she expected.” Fagertun describes a similar floundering: “I knew so very much about her and yet could not determine what to actually discuss with her.”

I have not yet met Lessa in person, but I wonder if part of our ease is because the qualities that make her a good narrator of my book are the things we share in common. We both indulge rabbit-holes of curiosity. We are both prone to gush.

Toward the end of our call, I told her I was conscious of my book being, at times, heavy. I wrote about bad things that had happened to me and other women. I hoped it had not felt too sad to live inside. She shook her head, and told me that she saw her work vocalizing the book as one of helping to facilitate healing. “I have never experienced sexual violence myself,” she told me, “so I don’t have to relive that trauma every time I hear about it or do a scene. I empathically relive it, but I don’t have to carry it on.” She said she had heard from listeners who found catharsis in getting to re-experience, through the safety of narration, moments adjacent to their life. Part of her goal with my book, she said, was trying to help the listener “renegotiate their contract” with fear.

When she said this, I realized I had been holding my breath. If I swallowed, I would cry.

*

I few days later, I got a message from an old acquaintance. “Loved your audiobook,” he wrote. “The reader was great. I kept forgetting she wasn’t you.”

__________________________________

Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell about Fear by Erica Berry is now available in paperback from Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Erica Berry

Erica Berry’s essays can be found or are forthcoming in The Yale Review, Gulf Coast, The New York Times Magazine, Colorado Review, Guernica, The Atlantic, and other outlets. Find her online at @ericajberry and www.ericaberry.com.