Emma Darwin on Writing About Her Family and Finding Inspiration in Artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder

“What glowed at me with such potency that I would willingly immerse myself for all the months of writing slog?”

The brute reality of a professional writer’s life is a Venn diagram of intersecting circles: i) what you’re capable of writing, ii) what you can sell, and iii) what you want to write. Every novel needs a “nonfiction hook,” because “This is about a place, people and subject you’ve never heard of and know nothing about” is not a viable unique selling proposition: something has to resonate with the potential reader, so they stop what they’re doing and buy.

But to write fiction, as Rose Tremain says, the “inert data” of “actual or factual” must “rise into the orbit of the anarchic, gift-conjuring, unknowing part of the novelist’s mind before it can acquire its own truth for the work in question.”

To write a novel about my Darwin-Wedgwood-Galton ancestors I’d gathered three centuries of family data: letters, books, memoirs, diaries, scientific papers, poetry, symphonies, articles, and autobiographical and other novels, and that’s not including biographies and family reminiscences. Yet if I ignored the data and gave my imagination free rein, I’d be doing a bait-and-switch on the reader, the famous names becoming shameless window-dressing.

Yet if I ignored the data and gave my imagination free rein, I’d be doing a bait-and-switch on the reader, the famous names becoming shameless window-dressing.

The common thread between these scientists, artists, poets, engineers, musicians and writers was what Frances Spalding describes as “persistence, intelligence and common sense” and the confidence that what matters is “arriv[ing] at an authoritative truth.” I was a product of the same family, so when it was their lives in question, how could my mind’s anarchic, unknowing desires overrule the authoritative truth of their data?

When the family novel crashed and burned, I found myself writing This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin—creative nonfiction exploring creative failure—and realized that writing fiction is a conjuring trick. We take the stuff of the world, and spin them into a narrative that will persuade the reader to read “as if” it’s all true; to ignore their parallel knowledge that none of it happened; to willingly make a trust-fall into the story’s arms. In the family novel I’d spectacularly failed to pull the trick off.

But what makes an artist is what Alan Bennett’s W.H. Auden calls “the habit of art,” and This is Not a Book showed I was at least capable of telling a story. In my chuck-it-all-in habit notebook I asked: what sits in my personal sweet-spot of can write, can sell and want to write?

What did I keep finding myself going back to? What glowed at me with such potency, such mystery, that I would willingly immerse myself for all the months of writing slog?

Can write was easy. All my life, the relationship of the past and the present has been how I experience the world: what each illuminates about individual humans in the other is the mainspring of my writing. Historical fiction it would be.

Can sell: What might that something be, that would resonate with potential readers? Definitely not words—other people’s words were my downfall last time—and not music—it’s by far the hardest art to evoke—but I do know something about images. Writing is my marriage but photography is my mistress, and though I’d been defeated by Art at school, Art History was pure joy. An artist, then?

And want to write? What did I keep finding myself going back to? What glowed at me with such potency, such mystery, that I would willingly immerse myself for all the months of writing slog?

Ten years before, in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, I’d stood in front of Hendrik Avercamp’s Winter Scene with Skaters, a classic of a genre established by the great Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and been overwhelmed by an aching memory of happiness.

It was 1973, I was nine, and my father’s work had taken us to Brussels. It was by no means the zingy city-break hub it is today, but the unbroken sweep of the European Community that Britain had just joined was spread out before us. Later, Brussels itself and the battlefield of Waterloo made their way into my first novel The Mathematics of Love, and Bruges into my second, A Secret Alchemy: clearly, this was a place I kept going back to. Where other teenagers had pop stars on their walls, had I not had a poster of Bruegel’s Census at Bethlehem?

Bruegel?

What is the power of any image, that we will stare, buy, commission, cherish, or report to the police or the Inquisition?

I bought a book and dug around online, and found that we know remarkably little about his life. Here was a wide, white space on which I could write, but I knew I’d never be able to inhabit Bruegel’s mind and spirit as he painted.

Then I discovered that Herod’s soldiers, who can be seen in every one of Bruegel’s snowy Flemish Nativities, are also Philip II of Spain’s. Philip’s repression of Protestantism in his Netherlandish dominions united political and religious resistance, and in 1566, when Bruegel was reaching the height of his powers, four hundred cities, towns and villages erupted into an organized, revolutionary, image-smashing Beeldenstorm.

Why do people smash religious images, I asked myself: what is the source of such images’ power that people are desperate to destroy? What is the power of any image, that we will stare, buy, commission, cherish, or report to the police or the Inquisition? And what does that mean for a painter like Bruegel, who paints Nativities but also jokes, horrors, landscapes and above all ordinary and gloriously human humans?

His vocation as a painter must have been as central to his self as vocation is to those who work in religion. But contemporary historical fiction, full of humans driven by love, sex, war and art, so rarely explores what’s going on inside those driven by faith.

Vocation in art and vocation in faith, that was my way in: vocation, and what happens when love, allegiance or obligation pull the other way, and all in a land divided even to the point of death over what faith is, and what art is for.

Bruegel blinked, tossed off the last of his ale, then poured them both some more. ‘I think you would make a good Sint-Michaël. New to the job, uncertain, young—and suddenly you’re in the greatest battle of all. Valiant, and frightened…’

He named the painting The Fall of the Rebel Angels.

My way into this world, and my way back into writing, turned out to be Gillis Vervloet, the Bruegel boy.

__________________________________

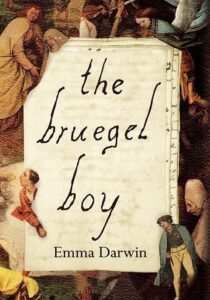

The Bruegel Boy by Emma Darwin is available from Holland House.

Emma Darwin

Emma L. Darwin is an English historical fiction author, writer of the novels The Mathematics of Love and A Secret Alchemy and various short stories. She is the great-great-granddaughter of Charles and Emma Darwin.