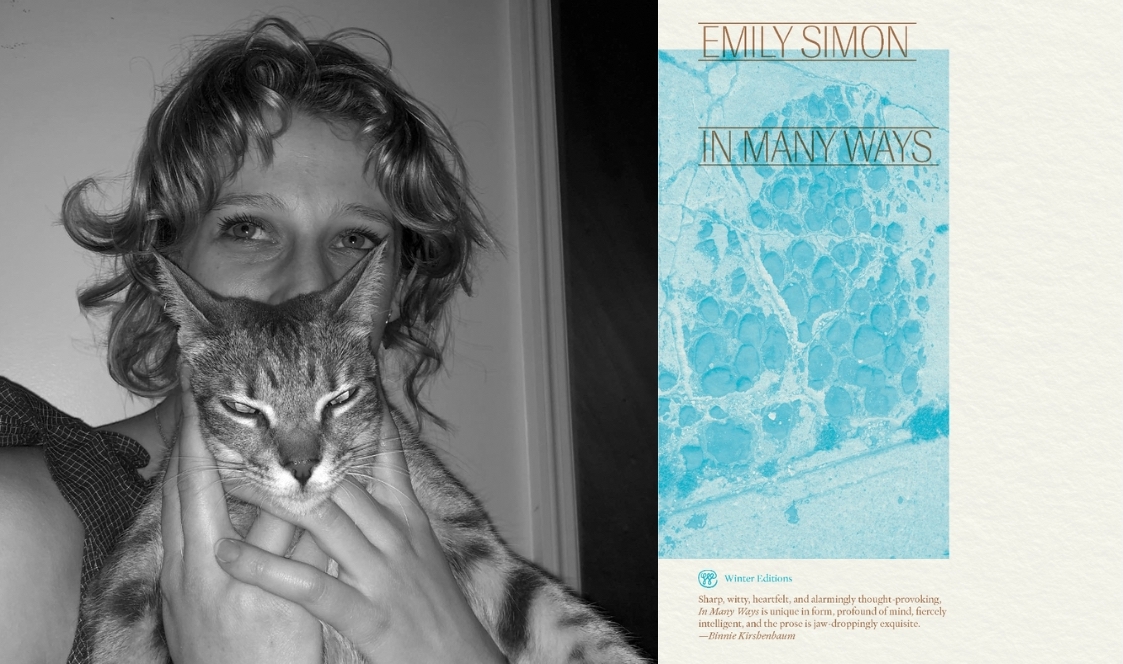

Emily Simon on Language Games, Perspective, and Inheriting a Tradition of Complaining

Ross Simonini Speaks with the Author of In Many Ways

I met Emily several years ago at Columbia University, where I was teaching and she was studying in the MFA writing program. She was one of my students in a seminar on process, where students dramatically experimented with the methods, times, and circumstances of their writing. Many students can have difficulty working outside of their comfort zone, but Emily seemed to relish every challenge, submitting a range of gorgeous curiosities, all of which hummed with her distinctive, vibrant voice.

This was her first semester and I remember how she filled the classroom with her exuberance. You could feel this energy in her poems, and in the way she interacted with the other students. She engaged every topic, every reading with heightened criticality. In class, she prodded at wandering lines of conversational thought (including my own) and provoked when she deemed it necessary. At one point, she almost didn’t return to class, after feeling her own intensity had become too fiery for the room.

Emily and I have stayed in touch over the years since she left Columbia and began to teach her own classes. In this time, she has continued to pack her unbridled energy into compressed nuggets of text, such as those in her first book, In Many Ways, a work of art as fragmented and wonderful as the fussy human personality.

–Ross Simonini

*

Ross Simonini: Do you still write poems on your phone?

Emily Simon: I do. I’m writing on my phone now.

I’m a very fast texter, and maybe I like to imagine I’m texting myself when I’m writing. If it were a more formal exercise, if I were sitting upright at a desk, for example, I’d feel something like stage fright, performance anxiety. I’d be much more precious about my work. So I’ve found a chattier way onto the “page” through my phone.

My teaching job reminds me often of the value of speech-to-text. For me, it’s proved most useful in the middle of the night, when I roll over in bed and hit the voice record icon in my Notes app. I speak very slowly and clearly into my phone.

I’m admitting to the intimacy between me and my phone, in public, in private, in transit, in bed.

When I write with pen and paper though, it’s usually to try out some kind of experiment. Language games are good practice for the real thing.

RS: What language games do you play?

ES: There’s the one that appears in the book, which began with a suggestion from an astrologer—to ask questions with my right hand and answer with my left in a big blank journal. The astrologer wanted me to access my more childlike self, which apparently is connected to the right brain by way of the left hand. I was so surprised by what I had to say through this exercise. Or by the correspondence that was suddenly happening, suddenly possible. It actually scared me a little, so I haven’t tried that game in a while.

I think the Emily in the book, or that “I,” functions as “me” and “you,” too. Which isn’t to say that no one else is there; there are many others.

The other night, my friend Sylvia and I each tore some of those big blank pages out and we took turns prompting each other with sentence starters. For example, “I believe,” “I don’t,” “I almost,” etc. They all began with “I.” We wrote to the end of the page and then swapped our pages. We went back and forth reading each other’s lines out loud and recorded ourselves doing this, so when you play the whole thing back, it sounds continuous. And it’s funny how you have me on record saying all the things Syliva wants, regrets, can’t stand, etc., and vice versa. She and I enjoy collaborating sometimes.

RS: What’s your teaching job?

ES: I’m a high school English and Creative Writing teacher at a school for students with language-based learning disabilities. I feel very lucky that this is the place where I’ve been able to teach for almost two years now—and I’m so new to teaching. There is a sense of humor and play at this school that I think is so valuable. I think most of the kids feel at home here.

Between teaching and writing, I live a sort of double life. One life is practical, rational, regimented, and the other happens everywhere else, or in between. When I’m a teacher at school, I’m so concerned with the lives of others. I’m taking great care, I’m so invested. But as a writer…I’m just not that kind of writer. I don’t write about individual, discrete lives. I’m not so interested in character or plot.

RS: Are you also disinterested in characters and plots in other books? In films?

ES: I care a lot more about voice, separate from the idiosyncrasies of a “character.” Voice is like the attitude and the atmosphere of the thing. Maybe voice is even the moral center.

RS: With the first-person perspective you are using, how do you do this teasing out of character from voice?

ES: Do I? Tease out character from voice? I think I’m just so interested in voice, I trust that the rest comes along with it.

RS: You spend some time wrestling with the “I” in this book. After doing all this wrestling, who is the literary Emily device and what’s your relationship to her? Is she smarter than the Emily I have known? Amplified? Subdued?

ES: No way is she smarter. She might be more organized.

I think the Emily in the book, or that “I,” functions as “me” and “you,” too. Which isn’t to say that no one else is there; there are many others. But the correspondence I imagine threading the book together is really between me and myself, subject and object. Both are Emily.

I’m not interested in if or how this Emily reflects me (or onto me). Emily—that “I”—is a formal device, a grammar. In lieu of conventional, linear time, there’s a troubled and troubling “I.”

RS: Can you give me some examples of “I” functioning like this in other books?

ES: The first example I ever encountered was in The Waves by Virginia Woolf. And then I kept looking for more. I ended up writing an academic Honors thesis in undergrad about Maggie Nelson and Ta-Nehisi Coates, with some mention of Knausgaard… I was thinking about the “I” and “you,” and I wanted to look at very different kinds of “self” and struggle.

More examples: Annie Ernaux. Sophie Calle, another French writer. Amina Cain, I think. I’ve been reading Trisha Low’s book Purge, and Jen George’s The Babysitter at Rest. I also want to mention Erica Hunt’s 2014 LA Times book review of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, which brilliantly problematizes the I/you.

RS: Can you talk a little more about the “you?”

ES: I think the I/you can insinuate a boundary, a difference and a distance—refusal, impossibility, alienation; and it can also insinuate a kind of mirroring, the closest proximity—kinship, discovery, reverence.

RS: Do you ever think in terms of fiction and nonfiction?

ES: I don’t! Every story is inflected by perspective, which is not just the difference between you there and me here, but also the difference between you then and me now. I can go anywhere I want in my story, in my version. I can even time travel. I can tell the story one way, two ways, or more, and all of them might be true. Why should I ever make my mind up?

My book In Many Ways exploits my life, it exploits me and my memories and ideas, to tell the truth. And you can see the construction, the artifice. It’s sort of like reality TV in that it’s poetry and fiction. But genre doesn’t matter so much to me. Genre is always taking an ethical stance on style and structure—on how to tell the truth.

I am not denying that historical truths and incontrovertible facts have important lessons to teach us, wonderful and terrible gifts to bestow. I am also not suggesting that I can pantomime or replace anyone else as I play with perspective, fact, and fiction. I’m saying that the “truth” is always mediated by some observational lens or device, by some form of art. The “truth” never arrives uncontaminated. There is art in everything we say.

RS: Are you a truth-seeker?

ES: Not exactly, no. “Truth-seeker” sounds like wizard.

RS: And you are not a wizard?

ES: I am so very mortal.

RS: How is genre “taking an ethical stance on style and structure?”

I’m no academic, but isn’t genre is about taxonomy, canonization, even hierarchy? And these imply a kind of ethics, in and out, right and wrong. I reject those codes.

RS: Embarrassment is a preoccupation for you. Do you stir up energy from this feeling? Do you feel embarrassed by this book?

ES: It’s a very tricky business, getting myself right in public. I want to make sense to you, but making sense demands no small sacrifice of artless fun; the kind of fun that is only possible before our meeting, afterwards, or apart from you. I’m talking about the party I have in my head without you, by myself, alone.

How can I avoid affecting authenticity in public? Can my affectless self survive with you, outside of me?

As I report on my affectless interior, make some kind of poor rendering with my body, with speech, etc., there will be devastating misunderstandings between us, and I will feel so embarrassed.

Embarrassment is frustrating, though, and I can appreciate what frustrates me for holding my attention so long. Embarrassment happens again and again between me and you. I keep writing into that space between us.

RS: Can you give me your definition of “embarrassment?”

ES: When I don’t do myself justice in public. When I perform myself all wrong. When I want something from you, or when you are the thing that I want, and I make this real desire known to you. In all this, there is a terrible risk of embarrassment.

Desire, especially, is exposing. When we say something like “an embarrassment of riches,” aren’t we also insinuating desire? Too much want.

RS: I often feel that being an artist is inherently an act of embarrassment. There’s the desire to make something that isn’t in the world already, and the desire for it to be seen and, maybe, praised.

ES: I understand that. It makes sense that audaciousness should be embarrassing, but I don’t feel that way myself. Maybe it’s because I’m not a man. I’m more than happy to be an audacious woman.

RS: Where do you place yourself on the social spectrum? Awkward? Affable?

ES: I don’t know why this question makes me laugh. I want to answer it. I love talking, I love listening, I love being out and about. I really love people. I feel so much affection, but I don’t know if that’s apparent to others. And I can stay out all night. I don’t enjoy very crowded or loud places, though. You don’t want to see me there.

I was compared to a cartoon character in the intro to an interview once, and I didn’t love that…or I didn’t know what to do with it, and I’m not sure it’s a fair comparison. What do you think about that?

RS: Which cartoon character?

ES: It wasn’t a specific comparison. Maybe I would have appreciated being compared to a specific cartoon character.

RS: And which one would make you feel appreciated?

ES: Maybe a Roz Chast character.

RS: You write about the relationship between artistry and misery. What is your artistic relationship to your own suffering these days?

ES: There’s an important difference between misery and frustration. I embrace all kinds of frustration in my work and probably my life, too. I am endlessly complaining, or chewing on something, trying to work it out. I found myself lying around a lot last fall and I started thinking about that—what lying down means, why and how and with whom we lie down. Maybe this is how I turned misery into a frustration. Misery alone is just a hole.

RS: Do you enjoy complaining?

ES: It’s second nature to me. I definitely enjoy it, too, it entertains me (my own complaining). My friend Matthew said recently that I complain a lot, maybe more than anybody, but it’s always about petty things, and he said that was a good thing. I can get heated about matters of Justice, but I wouldn’t call that mode complaining.

RS: Do you see your writing as a kind of complaint?

ES: Yes, the same way I see frustration as a come-on. Of course, complaining in writing is very different than complaining to Matthew.

RS: Is complaining a cultural tradition for you? A familial one? Social?

ES: I’d say it’s definitely an inherited, cultural tradition. My mother and her sister both have a real facility with language, which comes alive when complaining is possible.

Grammar and usage books make me cringe, especially in the way some perform their own proposal for a correct style and structure, grammar, etc. I’d rather see a more liberated poetic. I love sentences, just let them be.

RS: What are you complaining about most often these days?

ES: With my friends, with Matthew? I would remember if I complained about more important things. Complaining doesn’t lead to a meltdown. Like I said, getting really heated about things is different.

RS: In the book, you have some complaints around language and its limitations. What are some of your major complaints around language as it exists in the world around you?

ES: Language itself has so much potential. It’s my own failure to use it that frustrates me. And I’ve been jealous of others’ incredible fluency and creativity.

Is social media a generative field for language play? No. There’s a complaint in the form of a question.

RS: Do you enjoy reading grammar and usage books?

ES: Nope. With the fantastic exception of Joseph T. Shipley’s Discursive Dictionary.

RS: For such a language-focused person, why don’t you enjoy them?

ES: Grammar and usage books make me cringe, especially in the way some perform their own proposal for a correct style and structure, grammar, etc. I’d rather see a more liberated poetic. I love sentences, just let them be.

______________________________

In Many Ways by Emily Simon is available via Winter Editions.

Ross Simonini

Ross Simonini is a writer, artist and musician. He edits interviews for The Believer magazine, produces The Organist podcast and conducts interviews for various magazines. His debut novel The Book of Formation is out now with Melville House Books.