Emily Bingham on the Material Culture of White America’s Song to Itself: “My Old Kentucky Home”

“It was from the outset a blackface minstrel tune, entertainment built on slavery and the trade in human beings.”

I love the hunt. If you look hard enough, dig deeply enough, you will unearth treasures. When I began researching the life story of an American song from the 1850s, I knew it represented multiple things: a blackface minstrel hit by Pittsburgh’s Stephen Foster, often called “the Father of American Music;” the official anthem of both the Kentucky Derby and the Bluegrass State (where I was bred and born and still reside); and a house forty miles south of Louisville christened “The Old Kentucky Home,” a hundred-year-old tourist attraction. I knew those things, as I stepped into the archive to learn the song’s history.

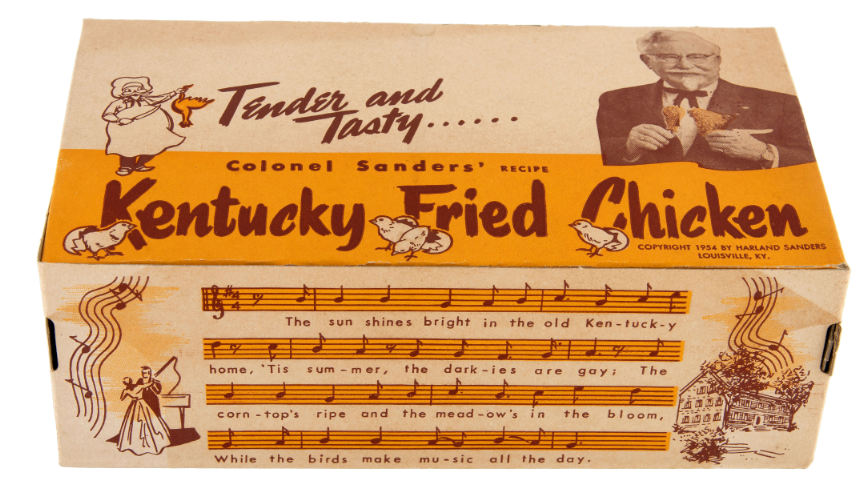

Kentucky Fried Chicken takeout box, collection of the author.

Kentucky Fried Chicken takeout box, collection of the author.

I was not prepared for the mountain of material culture the song has generated. Objects bearing its stamp range from predictable postcards and generations of songbooks and sheet music to postage stamps, doorbells, bracelets, barware, garden flags, fried chicken boxes, duvet covers and throw pillows, and much, much more.

Yet “My Old Kentucky Home” was never just a pretty song. It was from the outset a “touching” blackface minstrel tune, entertainment built on slavery and the trade in human beings. It says a great deal about this nation’s ability to ignore uncomfortable aspects of its history that this same song offered white Americans a soothing and sentimental cocktail generically evoking old times, papering over the realities of slavery and Jim Crow. (Click here to listen to singers performing the 1853 tune.) Over the decades, “My Old Kentucky Home” became a kind of sonic monument—white America’s song to itself.

Music enters us, becomes part of our breath, and this song is sung en masse each year at the Kentucky Derby by 150,000-plus spectators. It brings nostalgic tears to millions of eyes. It rings out on state occasions and at University of Kentucky basketball and football games (which many here equate with statewide occasions). Over the years, I have grappled with the ways this haunted melody became ensconced in actual homes, morphing onto things that were touched and held close, ornaments caressed by countless hands and eyes and lips. These objects may seem banal, but I believe they too make deep impressions.

The pages of a nonfiction book can’t convey the material emanations from Foster’s song over 170 years. They could fill a small museum, and perhaps some institution will undertake an exhibition. But I wonder: what is missed when the story of “My Old Kentucky Home” is told without accounting for its physical manifestation in everyday lives and its potent presence in the consumer culture? How has the song’s meaning been shaped by the way it has been acquired, possessed, collected, and worn?

“My Old Kentucky Home” economics began with twenty-five-year-old Stephen Foster—America’s first professional songwriter—being paid two pennies (about eight percent) as a royalty on each copy of official sheet music of “My Old Kentucky Home” that was sold. (Nobody could control the myriad pirated editions.) Scholars estimate nearly 70,000 copies of the song were bought in the first decade, but that was not enough to keep him afloat. Foster died in 1863, age thirty-seven, in New York’s Bellevue Hospital with thirty-eight cents to his name. Of course, his New York publishers made a great deal more money off the song, as did the blackface minstrels, whom one critic dubbed “the songbirds” who used it to entertain audiences across the country and the globe.

Button made in 1904. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Button made in 1904. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Kentucky didn’t make much of the melody at all until the turn of the twentieth century. Jim Crow segregation was taking hold in the nation, with Plessy v Ferguson (1896) codifying the lie of “separate but equal” treatment under the Constitution. The largest physical manifestation of the song surely was the Kentucky building at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, which deployed the tune as a brand to attract people and, state boosters, hoped, their money in the form of investments or tourism. Foster’s music floated out of the wide open doorways every hour of every day. Whereas Black fairgoers couldn’t get a drink of water because that would mean having separate glassware, thousands of visitors left the “New Old Kentucky Home” with printed copies of the melody as keepsakes.

Kentucky seemed to give freely of itself and its hospitality, and more people visited its building than any other outside Missouri’s. White America was embracing (or at least tolerating) racial segregation, racial terror, and disfranchisement. To the horror of leaders like veteran abolitionist Frederick Douglass and millions of Black citizens, the establishment decided it was time to let Civil War bygones be bygones and get back to business. A familiar sentimental song that invoked an antebellum Kentucky plantation where “the darkies are gay” set the ideal mood. Souvenir buttons asserted that anyone could own at least a symbolic piece of the place. The slogan: “Ky. Home—World’s Fair—‘It’s Part Mine.’”

“My Old Kentucky Home,” one observer noted at the time, brought a poor state “more publicity than any other one thing.”

Compact case, undated. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Compact case, undated. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Two decades later, Foster and his song were officially enshrined when The Old Kentucky Home opened as a tourist attraction in the small town of Bardstown, now known as the beating heart of Kentucky’s bourbon industry. The only dwelling Foster mentioned in his song is a slave cabin. Yet visitors from everywhere came to see the plantation house. Here, they were told (according to whole-cloth myth) Foster was an honored guest; here he set down the “immortal melody.” Visitors then took bits of myth home with them—ashtrays, matchbooks, and compact makeup cases like one a friend sent me after a visit to an antique mall. Someone held this round pink vision of home in her palm and used it to feel more beautiful before clicking closed its pink enamel cover and slipping it into her purse.

The Kentucky Historical Society has metal shelving reaching into the rafters to hold the state’s physical patrimony. One item is a framed counted cross stitch pattern from 1980. The song’s original lyrics, “The sun shines bright on the old Kentucky home / ‘Tis summer, the darkies are gay” waft above the iconic brick Bardstown house sewn in red.

Sheet of “My Old Kentucky Home State Park” stamps made in 1992. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Sheet of “My Old Kentucky Home State Park” stamps made in 1992. Credit: Emily Bingham.

Part of writing my book became about my own entanglement with the song. While planning my wedding in the mid 1990s, I got to select the stamp for the invitations. An almost childlike, sunny depiction of the Bardstown house had been created to honor Kentucky’s bicentennial, and once the invitations were printed, we sat with a damp sponge and sheets and sheets of perforated paper, gently tearing and wetting and sticking them on, our fingers smelling of US Postal Service glue. The stamp’s stately and cheerful scene adhered to my own happy anticipations of a special day long before I knew what “My Old Kentucky Home” was really about.

Ceramic plate from Stephen Foster Series by Willoughby Ions, courtesy Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Ceramic plate from Stephen Foster Series by Willoughby Ions, courtesy Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Foster hailed from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and one of the most fruitful sources for my book about his song were the archives held at University of Pittsburgh. Over the course of the 1930s, the Indianapolis pharmaceutical executive J. K. Lilly collected and disseminated everything he could find about the songwriter. He called it “Fosteriana,” and passed it as an endowed gift to the school in Foster’s home city. I spent weeks at “Foster Hall” at a library table groaning with everything from letters to letter openers, drinking glasses to magical glass lantern slides that projected the “story” of “My Old Kentucky Home.” Then I pulled from a box a pastel-colored dinner plate.

The chorus to “My Old Kentucky Home” goes like this:

Weep no more, my lady,

Oh! weep no more today!

We will sing one song

For the old Kentucky Home,

For the old Kentucky Home, far away.

The figure of the “lady” hovered in my mind from my earliest memories of the song. Who was she? When my husband first came to Kentucky at Derby time, he was struck by the hoop-skirted women who greeted air travelers with baskets of Bourbon-laced bonbons. An antebellum atmosphere seemed to stretch across the weekend, with that lady of the chorus as a sort of center pole.

A logical reading of Foster’s lyric might suggest that the “lady” was the enslaved man’s beloved back in Kentucky, and he sings to her, from the Deep South where he is to die in a sugar cane field. This might sound sympathetic, but blackface as a genre only laughed at Black “ladies”—actually cross-dressing white men, their faces smeared with burnt cork so they could act out their twisted fantasies of “blackness.” Another interpretation might suggest that the “lady” was the “mistress” of the plantation, someone who dressed like the women in the Louisville airport. But intimacy between a Black man and a white woman was an even more mine-filled potentiality than a “lady” who was enslaved.

Enter artist Willoughby Ions of Richmond. In 1941, she created a hand-painted series of Stephen Foster dinnerware, which sold in an upscale Manhattan department store. For “My Old Kentucky Home,” she depicted a white “lady” in a garden or grove, with a big house in the background. She cries into her handkerchief. A Black man kneels at her feet, pleading with her to “weep no more.”

The shorthand of an object conveyed what few were willing to express in so many words: that a white songwriter’s imagined depiction of a man sold away from his family to die was never really about the people it purported to be concerned with. It was about the satisfactions, hierarchies, and sentiments of the race that created, staged, and bought the song.

Who ate off these plates? Did they hang on walls? Someone dusted, soaped, and dried them. The plate’s charming style reveals a brutal reality about “My Old Kentucky Home” and gender and race in America. It unlocks the ugliness of what for generations was expected—even required—of Black people when it came to white feelings. Comfort. Assurance. Service.

Vintage Hazel Atlas “My Old Kentucky Home” Big Top drinking glass made in the 1950s as part of a peanut butter promotion. Credit: find42, eBay.

Vintage Hazel Atlas “My Old Kentucky Home” Big Top drinking glass made in the 1950s as part of a peanut butter promotion. Credit: find42, eBay.

Vessels for beverages are the most common single category of three-dimensional representations of “My Old Kentucky Home.” There are shot glasses, jiggers, old fashioneds, double old fashioneds (highballs), coffee mugs, julep cups, beer cozies, and even a whiskey decanter created by the distillery Heaven Hill. A person can can toast, cheer, slake their thirst, mix a cocktail, or curl up holding any of these commemorative containers. Why the ubiquity? There’s the association with Kentucky’s signature spirit, Bourbon, of course; but it’s not a stretch that, for coming on a century, Americans have sold and swallowed as well as sung a song about slavery.

_______________________________________________________________

Emily Bingham’s My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song is available now via Knopf.

Emily Bingham

EMILY BINGHAM is the author of Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham and Mordecai: An Early American Family. She lives in Louisville, Kentucky. Photo by Jon Cherry.