Elie Wiesel on the Problem with Tolerance

"What Can I Learn From the Other? What Does He See That I Cannot?"

It is 2003. As Elie Wiesel’s teaching assistant, I have the responsibility for creating a draft syllabus for each course. I bring this draft to Professor Wiesel, who takes it with him to his New York home to edit; he adds a book, removes another, and sends back a note asking me to include supplementary articles. Though he offers different courses each year, avoiding repetition, certain themes recur. One of these is the theme of difference, diversity, otherness.

If we pay attention to the ways we discuss difference and diversity in our culture, we will notice hidden biases and leanings. In New England, where I live now, we often celebrate connection, speaking of what unites us as being greater than our differences. This is good, but it can lead to a subtle tyranny of sameness, to people living in echo chambers in which they surround themselves with those who think like them. Social media often exacerbates the problem.

In order to fight this tendency, Professor Wiesel emphasized difference. “It is the otherness of the other that fascinates me . . . What can I learn from him? What does he see that I do not, cannot?” In his writing and teaching, he celebrated the madmen, the rebels, the outsiders, the underdogs—the others in literature and in life.

We each have blind spots, just as every candle casts its own shadow. Only when you place a second candle next to the first do the shadows disappear, illuminated by the other’s light. The beginning of dialogue is the knowledge that we can do this for one another.

*

Here is Professor Wiesel lecturing on Kafka, the master artist of alienation: “Kafka wrote, ‘I am a cage in search of a bird.’ What did he mean? That he recognized his own natural human desire to impose upon, to define, the other. Yet we remember what Kierkegaard wrote: ‘Once you label me you negate me.’ Kafka wrote The Trial and other works to remind us that we must not give in to the impulse to cage others; we must instead guard the otherness of the other.”

“Professor Wiesel emphasized difference. ‘It is the otherness of the other that fascinates me . . . What can I learn from him? What does he see that I do not, cannot?’”

Tammy, who grew up in the southern United States and has talked before about the endemic racism in her family, asks, “But how can we tolerate someone whose beliefs are fundamentally opposed to ours?”

Professor Wiesel says, “I don’t like the word tolerate. Who am I to tolerate you? I prefer the word respect. I must respect you even if I do not agree with you. In fact, my disagreement may be an expression of my respect for you. If I truly respect you, don’t I owe you my honesty?”

“What about truly evil people?” Tammy asks.

“For my own sake, I must still acknowledge their humanity. To act as if the perpetrator of evil is not human is to excuse him too easily. Animals do not commit mass murder. Not only that; animals do not make promises. We must remember to believe the enemy’s promises, for whatever he says, he will eventually do. If you think of him as simply an animal or a madman, it will be too easy to dismiss his words. The killer is as human as we are, but he has chosen to betray his humanity. Therefore, I must oppose him, stop him where I can, protest where I cannot.”

Tammy is not satisfied. Are her racist uncles “other”? Or are they merely the products of their education, misguided but still worthy of her affection?

“You know,” says Professor Wiesel, “for many years I was a journalist, and I was one of those who covered the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem. This was in 1961, after Eichmann was captured in Argentina by the Israelis. I had seen him once, in my little town in May 1944, though I did not know at the time who he was. He came with 50 Hungarian soldiers, and they deported the 15,000 Jews of my town. I only learned this later. And so I went to the trial to see whether he was human. Did he have two eyes, two ears; could he speak, smile? To murder so much must leave a mark on a man. At the trial, I watched him, day after day, hoping somehow that I would discover his inhumanity, that I would see some sign that he was not human, a mark of Cain. It would have been a great relief to see such a sign. But I saw nothing but a man, a bureaucrat, an accountant. Which means that two human beings made of the same elements, living in the same moment, the same place, may inhabit different moral universes.”

“To act as if the perpetrator of evil is not human is to excuse him too easily. Animals do not commit mass murder. Not only that; animals do not make promises. We must remember to believe the enemy’s promises, for whatever he says, he will eventually do.”

He continues: “In fact, Eichmann had a son who did not know his father’s blood-soaked past. When he found out, he still expressed love and respect for his father. Another son of a killer became a Catholic priest in an attempt to atone for his father’s unatonable sins. What does all this mean? It means that the most inhuman person is still human and will be judged accordingly. The ultimate other is a human being who has renounced his humanity, and we must bring him to justice. But this is the ultimate, the extreme. In our lives, most of the time we encounter simply the other, someone with vastly different beliefs. And we must struggle to understand him, to learn from him. The distance between us is necessary, not something to turn away from.”

Geoff asks, “Can you give an example of what this looks like in daily life?”

Professor Wiesel says, “I hope that you encounter the other here, in this room, those who hold different beliefs, values, worldviews than you do. When you do, you are faced with a choice. The choice is to listen, or not. I hope that you listen, really listen, not to find the other’s weakness but to find his strength. To disagree, to engage with controversy, does not mean to refuse to listen. On the other hand, to agree with someone does not mean to merge with the other. We are different; we have our own histories, our own destinies.”

“But,” says Tammy, “if I disagree strongly, don’t I have an obligation to try to convince the other person he or she is wrong?”

“That is fine, but the question is, how do you do that? Hegel said that real tragedies are not conflicts between right and wrong; they are conflicts between two rights. And there is a wonderful Hasidic teaching about this that says when two people disagree, and each one pulls away to his own side, his own opinion, a space is created between them. In this space, worlds can be created, provided the two antagonists do not fill the space with too many words. It is only because two people disagree that there can be such a space; were they to hold identical positions, there would be no room for innovation. In other words, conflict can be a good thing—if it is done well.”

“But why not try to identify with everyone, find what unites us?”

“Of course we must find what unites us,” says Professor Wiesel. “But we must not allow that search to collapse the distinctions between us. We know that in the Middle Ages, Church inquisitors tortured and burned people for the good of their victims’ souls. From the accounts that we have, we know that this sentiment was heartfelt, sincere. Therefore, we see that compassion itself is not enough; it is actually dangerous when it is married to the collapse of the otherness of the other. If I believe the other is identical to me, then I may apply my own calculus of pain and salvation to him. If, however, I acknowledge that his values, his priorities, are different, and if I respect that difference, then I can avoid this temptation.

“For the believer, there is a theological element to this as well. I must respect your otherness because it emerges from the ultimate other, God. Each of us is alone as God is alone. So who am I to judge you? I am a witness, not a judge. You know, in the Inferno of Dante, God is never referred to by name; the word God does not appear. Instead, the word Other is used. And this is true also in the book of Esther—God’s name does not appear. But these two elisions are for very different reasons. In the Inferno, because the characters are in hell, it is forbidden to speak God’s name. In Esther, it is because this book explores God’s hiddenness in history, how God works through natural or political processes. But in both places, God is the other. Once we really know that we are strangers to one another, we can begin to truly respect one another. From this respect, friendship can develop.”

“When two people disagree, and each one pulls away to his own side, his own opinion, a space is created between them. In this space, worlds can be created, provided the two antagonists do not fill the space with too many words.”

Rather than collapse the distance between us, between our worldviews and opinions, we need to sustain the gap, he says. In this way, we serve as “helpers against,” friendly antagonists, partners in clarifying our thoughts. Many of us spend so much moral energy on promoting connection that we sometimes forget to truly celebrate difference. We profess that all human beings are familiar to us. We claim to be so comfortable with different people, religions, ethnic groups, languages, skin colors, face shapes, that we no longer see them. There is a certain kind of jadedness that comes with such tolerance. Nothing surprises us anymore, and it is difficult to respect what you do not see.

Despite following a long line of mystics, Wiesel taught the very opposite approach. Rather than seeing the other as familiar, see the familiar as other, as if you haven’t seen that person before. He once told me that the highest level of friendship is when you never entirely know each other but instead always see each other anew, with a sense of surprise and an inability to take the other for granted.

__________________________________

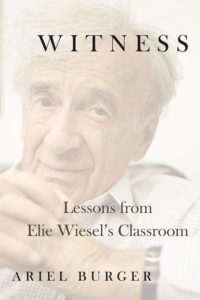

From Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom. Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright 2018 by Ariel Burger.

Ariel Burger

Ariel Burger is a writer, artist, teacher, and rabbi whose work combines spirituality, creativity, and strategies for social change. A lifelong student of Elie Wiesel, he spent years studying the great wisdom traditions, and now applies those teachings to urgent contemporary questions. When Ariel's not learning or teaching, he is creating music, art, and poetry. He lives outside of Boston with his family. His latest book, Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel's Classroom, is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.